SDG 14: Life below water

The oceans are in danger from many threats, such as climate change, overfishing and pollution. In order to sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems, our research focuses on fundamental ecological knowledge, strengthening resilience and finding practical solutions for healthier oceans.

Protecting the global oceans

Marine ecosystems are hugely complex, yet we need to better understand them in order to make the right conservation decisions. We study these ecosystems from many perspectives.

How overfishing can flip ecosystems

Ecologists know that too many nutrients in the sea will increase the growth of algae, which changes the underwater ecosystem. Ten years ago, through small-scale experiments, professor Britas Klemens Eriksson discovered that removing the top predators could also increase algal growth. He has now studied data on fish abundances along the Swedish coast going back 40 years and has analysed the entire food web, from algae and plant eaters to medium-sized predators, such as sticklebacks, and top predators such as perch and pike.

The results show that overfishing of top predators increases the number of sticklebacks, which then eat the plant eaters and even the larvae of the top predators. Thus, the ecosystem flips from being dominated by top predators to being dominated by algae. The results are important for the protection of coastal ecosystems. These ecosystems need top predators to keep the algae in check.

The importance of intertidal areas for sharks and rays

Intertidal areas are of greater worldwide importance to sharks and rays than previously thought. Researchers from the University of Groningen and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) have discovered that intertidal areas—coastal areas with sand flats that fall dry at low tide—are important feeding grounds and hiding places for, for example, endangered species of shark and ray. Protection of these vulnerable and dynamic intertidal areas is, therefore, of great importance.

Saving sea turtles by protecting sea grass meadows

For approximately 3,000 years, generations of green sea turtles have returned to the same Mediterranean seagrass meadows to eat, highlighting the importance of protecting these meadows.

Dr Willemien de Kock, a historical ecologist, discovered that sea turtles not only migrate between specific breeding places and eating places throughout their lives, but that they choose the same seagrass meadows across generations. De Kock combined modern data with archaeological findings.

Along the coasts of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, volunteers are active to protect the nests of the endangered green sea turtles. However, as Willemien de Kock explains: ‘We currently spend a lot of effort protecting the babies but not the place where they spend most of their time: the seagrass meadows.’ And crucially, these seagrass meadows are suffering from the effects of the climate crisis.

Cleaning oil spills using recyclable bioplastic membranes

Polymer scientists from the University of Groningen and NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences, have worked together on developing a polymer membrane from biobased malic acid that can be used to separate water and oil and potentially be used to clean up large oil spills in water.

The membrane is fully recyclable. When the pores are blocked by foulants, it can be depolymerized, cleaned and subsequently pressed into a new membrane. The scientists are confident that the methods are scalable, and are hoping that an industrial partner will take up further development.

Wadden Sea conservation

The Wadden Sea is the largest unbroken system of intertidal sand and mud flats in the world - and it is vital for many living creatures. We study this unique ecosystem, that lies so close to our University, hoping to understand, protect and restore it.

Wadden Mozaic: studying the subtidal Wadden Sea

The Wadden Sea is an extremely important ecosystem for a lot of species, which we need to preserve. To do this, fundamental knowledge of how the system functions is required.

The project 'Waddenmozaïek' studies the subtidal (continuously submerged) parts of the Wadden Sea. The aim is to give direct suggestions for nature management, on how to sustain and improve the natural values of the system. The project also aims to learn more about shallow sea ecosystems in general. In the video below, dr. Oscar Franken explains what the project entails.

Restoring the Wadden Sea with artificial reefs

Professor of Coastal Ecology Tjisse van der Heide is conducting research into the restoration of mussel banks and other bio-builders, as the living organisms that shape the Wadden landscape are known. Armed with a 3D-printer and industrial design methods, he became a bio-builder himself and is now searching for ways to restore these systems.

Bio-builders are species that help shape the landscape. ‘Bio-builders are both literally and figuratively the foundations of the ecosystem,’ explains van der Heide. 'But these natural ecosystems have disappeared in many places in the Wadden Sea. The mussel and oyster banks have long been overfished. Sea grass was badly affected by a disease, the construction of the Afsluitdijk, agricultural fertilizers, and phosphates from detergents.'

Now that the Wadden Sea is better protected and cleaner, we should see a return of these species. But this isn't always a natural process. That's where artificial reefs come in: they provide places where living creatures can settle on.

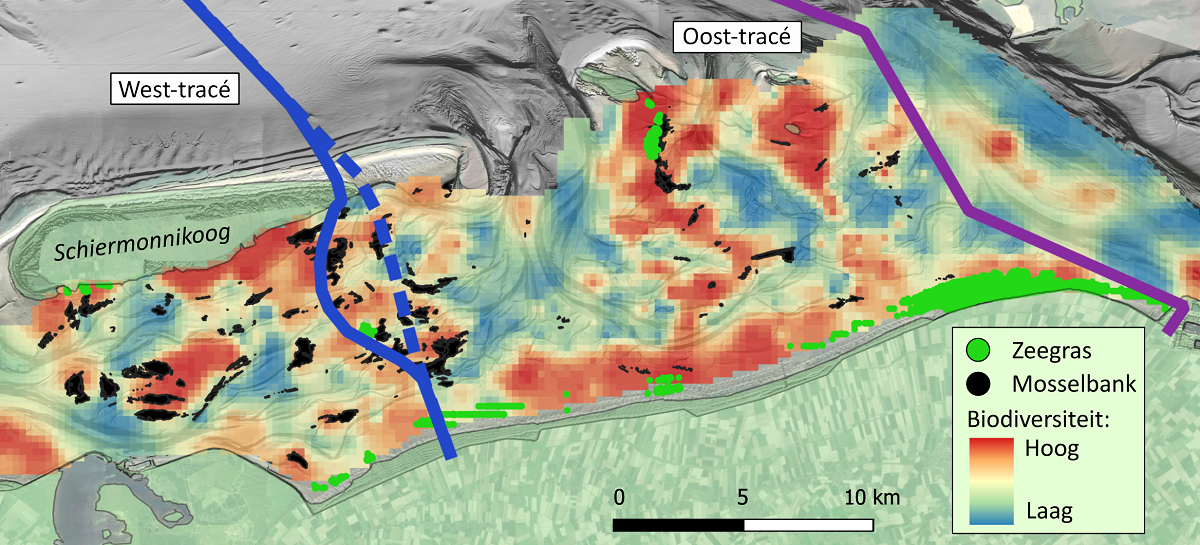

Preventing harmful policies by combining study findings

There are plans for a powerline called 'Eemshaven West', that will connect a new 700 MW wind park on the North Sea with the powerstation in Eemshaven. However, the trajectory crosses the most biodiverse hotspots in the Wadden Sea - and researchers have used combined study results to make a case against the planned trajectory.

Professor Tjisse van der Heide and colleagues combined recent sampling data of two monitoring programs: SIBES for the intertidal parts of the Wadden Sea and Wadden Mosaic for the permanently submerged, subtidal parts. Also, the location of current mussel beds and seagrasses, composed from cartographic data by Wageningen Marine Research and Rijkswaterstaat, were plotted on a map of the Wadden Sea.

Van der Heide: “When we project the proposed trajectory of the powerline on top this map, we see that it crosses some of the richest areas with benthic life, including several mussel beds. The plans of the architects of this power network unintentionally happen to connect almost as many biodiversity hotspots as possible.”

Bringing sea grass back to the Wadden Sea

Once upon a time, the Netherlands comprised vast seagrass meadows and had a thriving seagrass industry. As a result of disease, the dam and causeway the Afsluitdijk, eutrophication, and interference, the seagrass (Zostera marina) has all but disappeared. And with it, a remarkable ecosystem also disappeared, because seagrass is an important plant for the Wadden Sea and other similar shallow coastal seas. The grass retains the soil, dampens the swell, and offers food and protection to all kinds of animals.

Marine ecologist Laura Govers conducts research into seagrass restoration at the UG and at the NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research). On the Dutch island Griend, Laura booked success when she planted out young seagrasses that took root and have, by now, reproduced and formed modest new seagrass meadows.

Coastal protection

Sea level rise is a serious threat to the Netherlands. At the Faculty of Science and Engineering, we combine the neccesity to protect our coastlines with the possible improvement of our coastal ecosystems.

Dikes and artificial reefs

In November 2021, 48 artificial reefs were placed along the Lauwersmeer dike in the North of Groningen. They are part of a study into reef structures along dikes - and how dike transition areas can be 'softened', thereby improving nature and water quality. The outcomes of the research will be used in the design of a reef along the dike.

Britas Klemens Eriksson, professor of Marine Ecology, is positive about the first results: 'What we see is that artificial reefs along the sea dike work. We have found a lot of biodiversity on the reefs, fish as well as sessile organisms. That is really good news.'

Salt marshes can enhance coastal defence

Combining natural salt marsh habitats with conventional dikes may provide a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative for fully engineered flood protection.

Researchers of the University of Groningen (UG) and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) studied how salt marsh nature management can be optimized for coastal defense purposes. They found that grazing by both cattle and small herbivores such as geese and hare and artificial mowing can reduce salt marsh erosion, therefore contributing to nature-based coastal defense.

| Last modified: | 27 November 2023 2.30 p.m. |