Protecting Households’ Access to Essential Services in Times of COVID-19

| Date: | 05 May 2020 |

By Marlies Hesselman, University of Groningen, Faculty of Law, Dept. of Transboundary Legal Studie

Nearly two months ago, two Chairs of US House Committees observed that ‘[a]ccess to clean water is a basic human right at all times’ and that during the COVID-crisis it ‘would be reckless in the extreme’ to allow disconnections of people’s essential water supplies. The Chairs urged for a nation-wide disconnection ban as soon as possible. Similarly, on 11 March 2020, another group of US Congress members wrote that ‘access to clean drinking water is a basic human right’ (https://dankildee.house.gov/), and considered it ‘unconscionable that during an infectious disease outbreak, people would continue to be shut off from access to water’. These law-makers expressed concern that ‘some of the poorest communities in America pay the highest water rates in the country’. Surely, it must be possible, in a rich country like the US, that every person ‘has access to safe and affordable water’. These law-makers went a step further by calling for reconnection to essential supplies too.

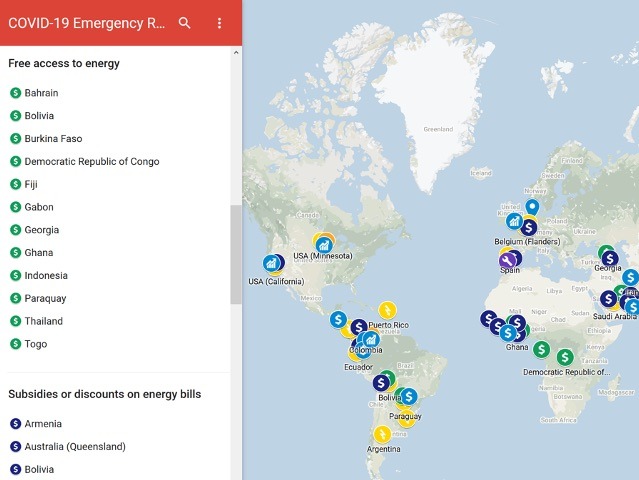

This post was written based on an extensive, non-exhaustive, inventory of global measures announced around the world in support of essential services access, with specific attention to access to energy services. The post aligns with the author’s research into the ‘right to energy’ and ‘human rights and essential public services access’. A Google Map was used to collect and map the COVID-measures on energy access specifically. The map can hopefully serve further transboundary (comparative) research and action. The map is currently being further developed by a consortium of researchers affiliated to the ENGAGER Energy Poverty COST Action, and shall be (re)published with further entries at a later time.

This blog powerfully show that world-wide, law-makers, utility regulators, sometimes even companies, have begun to announce and undertake a very broad range of temporary (emergency) relief measures to ease people’s payment burdens, or to secure continued access for individual and public well-being. Indeed, while even under normal circumstances States carry human rights obligations to protect peoples’ access to basic services, like water, energy and access to information, the COVID-19 crises throws a stark spotlight on the essential nature of household access to water, energy and ICTs. For, without water supply, energy services, phone or the Internet, women, men, children, the elderly, migrant communities, students and others are unable to meet their essential daily needs. Such needs may include personal and domestic hygiene (washing hands, clothes washing, utensil cleaning, surface cleaning, bathing) access to essential information, education, or communication. These services also form the pillar of basic living conditions, like having access to electric lighting, a sufficiently warm or cool home, or being able to cook, prepare and refrigerate food. Moreover, some health conditions require access to electricity to run life-saving appliances, like ventilators, or the refrigeration services for medicines.

Of course, the COVID-19 crisis also (again) exposes the extreme precariousness and high human costs of not having access to safe, affordable, accessible and reliable basic services in the first place. Those living in informal settlements , refugee camps , conflict zones , urban slum areas or rural areas run high risks of exposure to COVID-19, and are for this reason sometimes faced with severe containment measures. Those with pre-paid access to services , or off-grid access to supplies, may also need specific attention.

(Emergency) measures protecting people’s access to essential services

The inventory of measures reveals that the (temporary) emergency measures taken in support of extensive lock-downs or job and income loss, vary considerably, and may be taken in addition to existing social protection, like social tariffs, life-line tariffs or subsidies for services provision, or income or rental support measures. Emergency measures in the sphere of essential services access include:

-

Free access to essential services (e.g. Bolivia, (https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19) Bahrain, Burkina Faso, Fiji (http://www.fia.org.fj/getattachment/Home/PKF-summary-of-Fiji-COVID-19-Response-Budget-26Mar2020.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US), Indonesia, Thailand (https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1904580/cabinet-gives-nod-to-slash-power-bills#cxrecs_s), and more – see map)

-

Discounts or subsidies on essential services consumption (e.g. (https://www.seattle.gov/humanservices/services-and-programs/affordability-and-livability/utility-discount-program) Seattle, Ontario, Maldives, Malaysia, Panama, Fiji, Flanders – the latter for example a lump sum payment of 202 euro’s for 1 month of water and energy services)

-

Prohibiting disconnections (due to reasons of non-payment) ) and ensuring that people on pre-payment meters do not self-disconnect (e.g. Spain, Texas, Panama (https://www.panamaamerica.com.pa/economia/coronavirus-en-panama-consumo-general-de-energia-electrica-debe-disminuir-aseguro-la-asep), or UK, Flanders)

-

Providing (free) reconnections of service (e.g. 200,000 households in Colombia, many households in Detroit, (also here), Los Angelos, and see discussion on USA above and on map)

-

Offering delayed payment of utility bills (without fines for late payment) (e.g. Pakistan, Colombia, Bangladesh)

-

Offering (personalised) payment arrangements (e.g. Texas)

-

Delaying deferral of existing debts to debt collection agencies (e.g. recommendation in (www.aer.gov.au/publications/corporate-documents/aer-statement-of-expectations-of-energy-businesses-protecting-consumers-and-the-energy-market-during-covid-19) Australia)

What is striking, however, is that measures announced do not only differ significantly between and within countries, the measures are also not equally targeted at the services of water, electricity, gas and internet. For example, across Latin-America measures taken appear to differ considerably from country to county, from no measures, to significant deferral of the payment of bills, to subsidies and discounts, to disconnection policies. The same seems to count for Europe. For the vast territory of Australia, the Australian Energy Regulator instead, published a (https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/aer-statement-of-expectations-of-energy-businesses_1.pdf) Statement with 10 Principles on Expectations of Energy Businesses during COVID-19, proposing that companies implement a mix of the above proposals – without imposing any clear or specific obligations on all companies equally. Across the USA, supposedly about half of the federal states have put in place some COVID-response measures in relation to utilities (e.g. consider messages from Texas, (https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/seattle-will-keep-customers-lights-water-on-during-coronavirus-emergency-defer-taxes-for-small-businesses/) Seattle, and other US towns, here) despite aforementioned calls for nation-wide protection. The US-based Food and Water Action group maintains a list of COVID-related (water) utility protection measures across the country.

While protecting against disconnections and ensuring affordability during and after the crisis is extremely important, the matter of reconnection of essential services is an important concern too. The city of Detroit has begun a process of restoring access to water supplies for thousands of previously disconnected households. This is remarkable because only a few years ago, UN Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Water, the Right to Housing and Extreme Poverty severely critiqued this city’s massive water cut-offs for reasons of non-payment as “a violation to the human right to water and other international human rights”.

A human rights law perspective

From an international human rights law perspective, the COVID-19 crisis sheds new light on States’ (prior failure to adequately implement) obligations on access to essential services. In this sense, it is noteworthy that Argentina’s emergency measures were adopted with express recognition of the country’s obligations under international human rights treaties. While this blog post is not the right place for a full exposé of States’ human rights obligations in the sphere of socio-economic rights and essential public services, either in regular times or in times of emergency, the following comments deserve be made about States’ human rights responsibilities for essential service provision.

Firstly, access to essential public services, like water and electricity/energy services, is explicitly protected by a broad range of international human rights, enshrined in a range of binding human rights treaties. Relevant rights include the right to water (e.g. CESCR General Comment No. 15 2003), the right to life (in dignity) (e.g. HRC General Comment No. 36 (2018), para. 26), the right to adequate housing (CESCR General Comment No. 4 (1991), para. 8), or the right to health (CESCR General Comment No 14 (1999)) Access to water and electricity are considered underlying determinants of the right to health according to two communications by UN Special Procedures to Serbia (2016) and Nigeria (2013)). Moreover, access to information, including access to internet and access to electricity, has been affirmed as a component of the rights to freedom of expression and access to information, while access to essential health information is clearly tied to the right to health in CESCR General Comment No. 14 (1999).

What follows from these legal rights, and documents cited, is that all people are entitled to certain minimum essential levels of adequate, safe, clean drinking water for both personal and domestic uses. Water and electricity access also have to meet standards of universal service, i.e. must be available with sufficient quantity, quality, safety, regularity and be affordable to all (e.g. CESCR General Comment 24 (2017), paras. 21-22). States must consider regulation on appropriate pricing, tariffs and connection costs, and ‘design regulation in such a way’ as to ensure universal affordability (see e.g. communication Nigeria). As stated above, essential services access can never be made dependent on people’s (in)ability to pay. Affordability is essential. Access is key. According to CESCR General Comment No. 15 on the Right to Water, States have to adopt, as necessary: (a) a range of appropriate low-cost techniques and technologies; (b) appropriate pricing policies such as free or low-cost water; and (c) income supplements. Moreover: “Any payment for water services has to be based on the principle of equity, ensuring that these services, whether privately or publicly provided, are affordable for all, including socially disadvantaged groups”. In particular, “equity demands that poorer households should not be disproportionately burdened with water expenses as compared to richer households”.

While the right ‘regulatory mix’ in any country will likely depend on that countries’ setting and needs, and its available resources, the great variety of measures indicated in this post evidences that States have a considerable “toolbox” of regulatory measures available to them. This expressly includes the imposition of strong regulation and oversight on private (for-profit) sectors in favour of basic access and human rights.

Looking beyond the COVID-19 emergency: The need for a long-term perspective

It is important to finally observe that in implementing the COVID-19 emergency relief measures, States must consider the longer-term perspectives of households too. Any (temporary) relief offered now, must not lead to massive household debts and/or delayed loss of services later. Or to unmanageable higher levels of poverty. In this sense, it is positive to see that Colombia extended options for repayment of bills incurred during COVID-19 up to 36 months later, whereas in El Salvador households can take two years to pay back their electricity, water, internet and phone bills. In other countries, adjusted tariff rates are under consideration, including for up to five years. Such forward looking perspectives are essential for those in the poorest segments of society, who may struggle or fail to pay essential bills even under normal circumstances. It is extremely likely that many households will face additional challenges due to (temporarily) higher utility bills as a result of the prolonged confinement to homes, or due to loss of essential household income. In fact, in countries like Thailand (https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1904580/cabinet-gives-nod-to-slash-power-bills#cxrecs_s) or New Zealand, concerns about higher energy bills were cited as a key reason for implementation of (additional) emergency protection, e.g. in the form (https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1904580/cabinet-gives-nod-to-slash-power-bills#cxrecs_s) free or discounted electricity supply during a number of months, or double ‘winter energy payments’ to vulnerable groups.

All in all, the COVID-19 crisis thus raises questions about how to ensure human rights-compliant access to essential public services in the future too, after this crisis hopefully is under control. Indeed, after COVID-19, international human rights law will (continue) to make demands of parties to human rights treaties. It proposed here by way of final conclusion, that many of the current COVID-19 measures in fact offer excellent templates for further consideration of affordable access for most vulnerable groups in the future. In this sense, the COVID-19 emergency shall hopefully be a stepping stone for reinvigorated debate, agenda-setting and policy-making in the area of socio-economic human rights and essential public services provision, including as these agenda’s clearly intersect with agenda’s on health, education, poverty and equity.