Traditions in the Arctic in times of change

In 2018, Arctic Centre postdoc Sean Desjardins received an NWO Veni grant to study the resilience of Inuit traditional life in Arctic Canada. In this narrative, he tells us something about his interdisciplinary approach and how he co-operates with Indigenous communities. Besides his ambitions to performing high-quality research, Desjardins is clearly motivated by the relevance of his research for the area and for Indigenous societies around the world.

Sean Desjardins is a Canadian, but his interest in the Arctic actually started during his studies in anthropology in Florida. “The climate and society of Florida couldn’t be further from that of the Arctic. Nevertheless, it was this stark contrast that intrigued me. The Arctic is a massive sparsely-populated region, which, I would come to learn, has an incredibly rich ecology and cultural history. It is a history of immense change over the past couple of thousand years. How did Arctic Indigenous peoples deal with these changes while preserving their cultural identity and heritage? It’s this question forms the basis of my research over the past several years - especially the Veni I am beginning now.”

Lost traditions

Over the past several hundred years, traditional practices of Indigenous peoples across the circumpolar Arctic have been impacted significantly by both ecological and social stresses. Our collective understanding of climate change in polar areas is influenced by popular images of starving polar bears, but the livelihood of human beings is equally affected. What happens if one cannot reach his or her traditional hunting grounds because sea-ice is no longer seasonally predictable? If we also consider the impacts of colonialist policies that restricted residential mobility and encouraged cultural assimilation of Arctic Indigenous peoples, we begin to better understand the stress these communities faced.

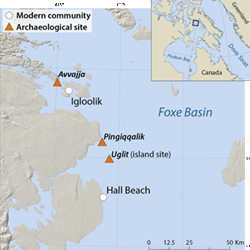

According to Desjardins, “the aim of my current research project is to determine how and why some culture-defining Indigenous practices, such as subsistence hunting, were successfully adapted to changing conditions, while others faded away. An ideal case study through which to examine this problem is the Inuit occupation of Foxe Basin, Arctic Canada.” There, the remains of sod houses can be found that were in use during the colder months of the year well into the 1950s; sadly, this tradition is no longer practiced. At the same time, a complex and vibrant hunting of caribou and marine mammals (mainly seals and walruses) has survived to the present day.

Traditional knowledge

To address this issue, Desjardins employs a unique combination of archeology and anthropology. Because Inuit are only half a century removed from a traditional, seasonally-mobile lifestyle, elders can be consulted before any archaeological investigation is carried out. Desjardins benefits greatly from this traditional knowledge, learning, for example, how house structures were constructed, and how particular animal species were hunted and butchered. In a region experiencing rapid and drastic changes, it is logical to combine these firsthand accounts with archaeology. “As an anthropologist and archeologist I easily see how the disciplines can benefit from each other, and we are very fortunate elders are here to share their knowledge.”

Establish trust

Of course, this type of research requires close co-operation with Indigenous communities. How can you establish the necessary trust? “For historical reasons, many Inuit are not very fond of researchers, government officials and others who say they mean well. Knowing the recent history of ‘Southern’ interactions with Inuit, who can blame them?” From 1850 until 1980 it was governmental policy to intern Indigenous children in boarding schools, often without the free, prior and informed consent of their parents. This was done in order to assimilate them into broader Canadian society. The painful scars of this historical injustice is still visible in the Inuit communities of Nunavut—Canada’s Arctic Territory. “I think it is important to stick to your promises and to show people that they can trust you. It’s not a quick process; I have been doing research in the area for many years now, and locals know I return each year, do good work and am accountable. I respect their stories and objects, and I do my best to take their cultural wellbeing into account.”

Desjardins continues, “This year, I’ll be working with Inuit youth as well as elders. Many Inuit want youth in their communities to know more about their history and traditions. I have partnered with the Inuit-run organization Inuit Heritage Trust to carry out a small archaeological summer school for high school students from the community of Igloolik, Nunavut. Not only will they learn about the archaeology and cultural history of the region, but they will also have the opportunity to learn directly from visiting elders.”

The Netherlands and the Arctic Council

Desjardins is clearly concerned about the Arctic and the fate of its population. In addition to documenting the long-term history of the region, he has the opportunity to influence contemporary Arctic policy as the Dutch representative to the Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG) of the Arctic Council. And why is the Netherlands - a non-Arctic country - part of the Arctic Council? “The Netherlands is officially an Observer State at the Arctic Council. But we are, I would argue, an ‘Active Observer.’ This country has a long, rich history of exploration, research and commercial interest in the Arctic; beginning with the 17th century Dutch whalers who established trading relations with the Inuit. The SDWG works to improve the social, economic and cultural lives of Arctic peoples. Given the great Arctic research being done by Dutch scientists, as well as our history in the region, the Netherlands has a lot to offer the Arctic Council.”

Lessons to be learned

Apart from the important issue of climate change there are additional lessons to be learned from Desjardins’ research. “The relationship between traditions and identity is the focus of my research. These themes are the subject of debate in increasingly multicultural societies all over the world; in fact, contentious debates around changing values and cultural traditions are held frequently here in the Netherlands. My research among Inuit is showing that those cultural traditions that survive and thrive are often the most flexible; many people tend to think of Indigenous traditions as almost sacredly static. In fact, experienced Inuit elders will often be the first to indicate that in order for traditions to survive, they need to adapt to change, be it social or ecological.”

| Last modified: | 06 April 2020 4.50 p.m. |

More news

-

16 December 2024

Jouke de Vries: ‘The University will have to be flexible’

2024 was a festive year for the University of Groningen. Jouke de Vries, the chair of the Executive Board, looks back.

-

10 June 2024

Swarming around a skyscraper

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...