Wout van Bekkum: portrait of a pioneer

He knows Jerusalem like the back of his hand, and runs into people he knows in the National Library as often as he does at the university library in Groningen. Wout van Bekkum, Professor of Middle Eastern Studies, is a familiar presence at the library, currently located on Jerusalem’s Hebrew University campus. ‘It’s an excellent social meeting point for people studying Judaism and related topics. I hope it will retain that function in the new building, near the Israeli parliament. In Israel, the academic study of Judaism and Hebrew is becoming increasingly politicized – it would be a pity if the move to the new location were to reinforce this trend.’

Text: Annemieke van der Kolk, Communication / Photos: Hesterliena Wolthuis

Exotic squiggles and curlicues

It was his love for exotic scripts that drew Van Bekkum to embark on the study of Semitic languages in the autumn of 1972. ‘At school, I was far more attracted to Greek than to Latin, because of the intriguing script. Even as a young schoolboy, I used to buy marked-down books full of illegible squiggles and curlicues: Arabic, Sanskrit, and occasionally even Chinese if I was lucky. Aware of my unusual fascination, my mother encouraged me to pursue this line of study instead of training to become an English teacher, which had been my original plan.’

Pioneer

‘In 1972, I was the only student to enrol for Semitic Languages and Cultures. There were about fifty theology students who were required to study Biblical Hebrew, but whilst most of them didn’t enjoy learning the language, I did. I often ended up having lessons on my own. I remember the professor sometimes asking us all to please open our books. That was funny. Most of the time I considered private tuition a privilege. Within my degree programme, I was one of the first to do a year of study in the Middle East and to go to Jerusalem’. As he thinks back, Van Bekkum chuckles. ‘It was an exercise in pioneering – there was no such thing as a Mobility Office back then! But I would recommend it to anyone. It’s such an enriching experience to have to survive on your own in a foreign country – and remember, there was no internet connection to keep you in touch with everyone back home. The most enriching aspect was studying together with Israelis, Palestinians, Druze people and Bedouins. It was 1977-1978. Sadat had just been to Jerusalem – I saw him. The Israel-Egypt peace negotiations were in full swing; Israel’s diplomatic position was strong, but the Palestinians suffered. You could discuss the whole situation with everyone, but even at that stage there were some nasty incidents.’

193,000 manuscript fragments

Of all the lectures he attended in Jerusalem, Van Bekkum found the ones on Byzantine and Andalusian poetry (taught in Hebrew and Arabic) the most fascinating.

‘Armed with this newly-acquired knowledge, I returned to Groningen. Professor Hospers was impressed. It was a relatively unexplored topic at the time, but he was fine with me writing a thesis on it, and then choosing it later as my PhD topic.’ Building on what he had learned in Jerusalem, Van Bekkum focused his PhD research on the Egyptian Genizah. Most of this enormous collection of writings – 193,000 fragments – were recovered from Cairo at the end of the 19th century and taken to Cambridge. ‘I was able to attribute a number of these fragments to a 6th-century poet from Palestine. In those days, you got to handle the original fragments, or you worked with microfilms. Nowadays everything is online, which is certainly convenient, but less tangible.’

Understanding society

Is it difficult to justify Hebrew poetry as a curriculum area? ‘Not really. Poetry might at first appear to stand in isolation, but you can’t understand a poem unless you are aware of its context. A poem belongs to – and reflects – a particular period. That’s why when I was Professor of Modern Jewish History in Amsterdam I gave a series of lectures on eleven European cities whose Jewish communities have made a significant contribution to the life of that city, such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Prague and Budapest.’

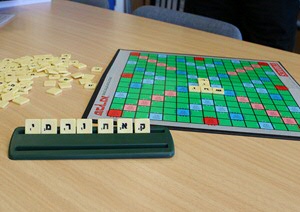

Scrabble in Hebrew

‘What time did you get out of bed? What did you put on your bread this morning and what are you planning to do today?’ These were the kind of questions Van Bekkum used to fire at his students in rapid Hebrew, and of course he expected equally rapid answers. As an ex-student, I remember how nerve-racking that was, and I might just possibly have simplified my accounts of certain aspects of my day-to-day life to make it easier to answer him. For example, anyone listening to my answers in Hebrew would have got the impression that I was extremely fond of cheese on my bread. It was just easier that way. ‘It’s the best method, though’, says Van Bekkum. ‘That’s how immigrants who come to Israel learn the language too.’ He takes a Scrabble game out of the cupboard. ‘We often used to play Scrabble in Hebrew during the last lecture.’

Scrapping Arabic not an option

Van Bekkum has been Professor of Middle Eastern Studies in Groningen since 2001. ‘A lot has changed since then. These days, our main focus is on history, religion, society and culture. Our students have good career prospects. They find jobs in the judiciary, in refugee work, in domestic and foreign affairs. They have unique qualities, one of the most important of which is their mastery of the relevant languages. We definitely want to keep the language element in the programme. Some students find it difficult to learn Arabic or Hebrew, but actually these are extremely logical languages. You know that.’ He looks at me, and I nod. Learning Arabic was sometimes just like maths. ‘But you have to keep it up’, he adds. I avert my gaze.

No sabbatical

Van Bekkum’s enthusiasm is a key quality of all his lectures. ‘It is my genuine desire to share my knowledge and skills with others. I hope that comes across. I have never not wanted to deliver a lecture.’ Which is just as well, given that on an average day Van Bekkum gives two to three lectures at Bachelor’s or Master’s level, on topics ranging from International Organizations and the Middle East to Judaism and Islam. ‘The new programme took a bit of getting used to, but I’m enjoying it now, especially the fact that the subjects are so varied. The Middle East is incredibly interesting. It doesn’t leave much time for my own research, and I also have plenty of admin and board work. In our field, it’s not easy for us to replace each other, simply because there are too few of us. Taking a year’s sabbatical isn’t an option.’

| Last modified: | 12 March 2020 9.23 p.m. |

More news

-

19 December 2024

Konstantin Mierau new Vice Dean Faculty of Arts

The Board of the University of Groningen has appointed Dr Konstantin Mierau as Vice Dean of the Faculty of Arts, effective 1 January 2025. Dean Thony Visser and Managing Director Sander van den Bos are pleased with the appointment and look forward...

-

10 December 2024

Time will tell: what tree rings reveal about the past

Ancient DNA analysis of bones, teeth, or plants can reveal family connections, population movements, and domestication pathways. Pınar Erdil tells more about it.

-

10 December 2024

Joëlle Douma wins the Stijlvoltreffer 2024 writing competition

On Monday 9 December, Joëlle Douma (5 vwo) from the Gomarus College in Groningen won the Stijlvoltreffer 2024 writing competition with her story ‘Ik haat Hanna’