Fraternalis Amor

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, literature lovers in the Low Countries started to unite in chambers of rhetoric. The rhetoricians, mainly men, focused on writing, reciting and performing poetry and drama in the mother tongue. They also exchanged their texts with each other for comments. The chambers were competitive, both inside and outside the walls of their towns. Trials of strength between members, national competitions and even festivals lasting several days were popular entertainment.[1] For that reason, the motto of the chamber De Distelbloem (The Thistle Flower) from Dendermonde, ‘Fraternalis Amor’ (Brotherly Love), perfectly describes the rhetoricians of the Low Countries.

In this virtual exhibition you become acquainted with the greatest literary movement in Dutch history.[2] Using old prints from Special Collections, this exhibition will shed light upon influential rhetoricians and popular genres in four slide shows.

Ars poetica

The organization of the chambers of rhetoric was similar to that of guilds. The dean or headman was the leader of the group. The prince (sometimes emperor) was seen as the head of the chamber. He provided capital and handed out prizes. The factor led the literary activities. His tasks included writing texts, directing plays and sometimes even composing music. The confreers were the ordinary members who paid for their membership and sometimes also had to make financial contributions to certain festivities. Finally, there were the personagiën – the members who paid in kind. They worked, for example, as actors or extras in plays, or helped to set up the stage.

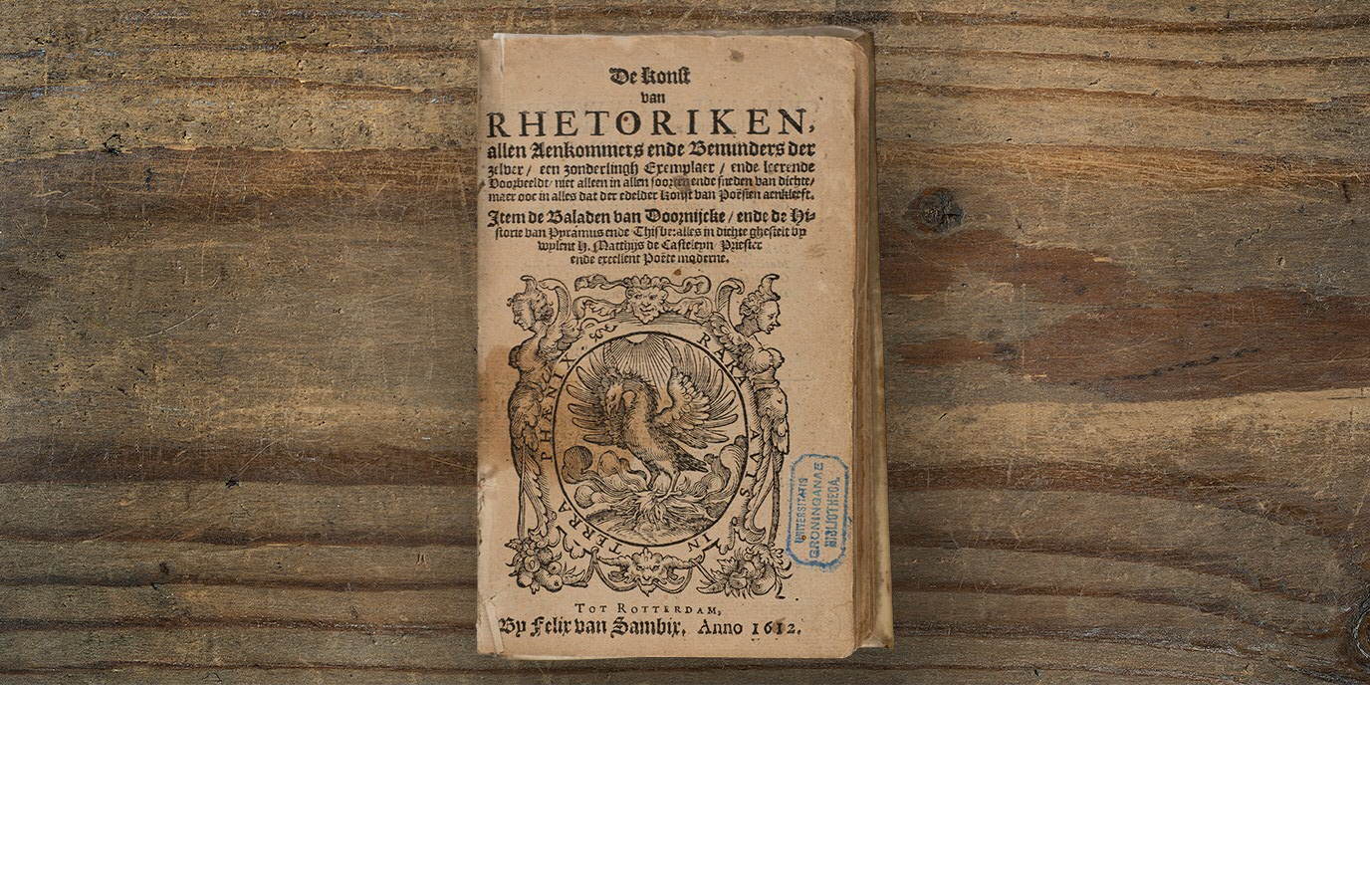

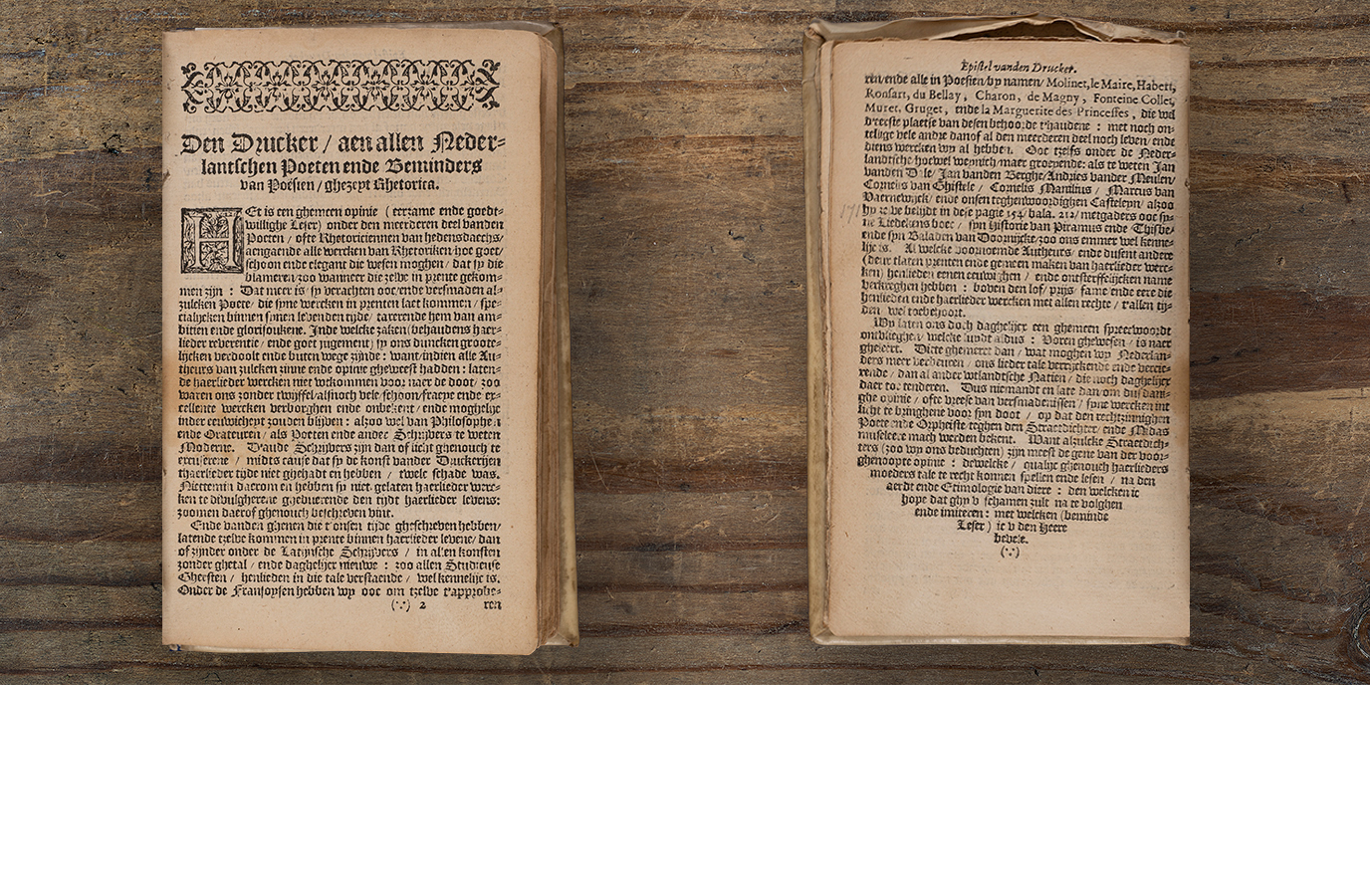

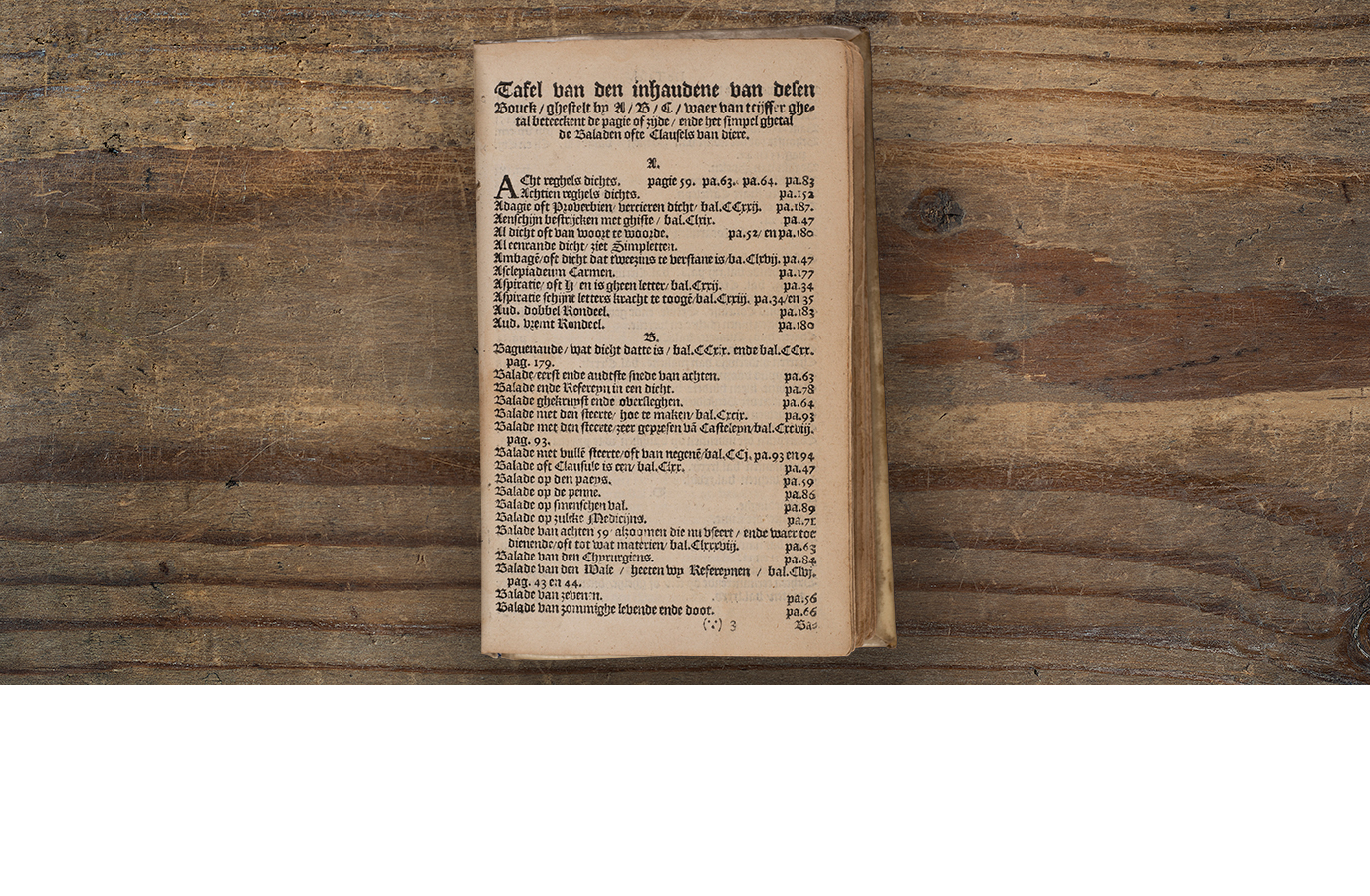

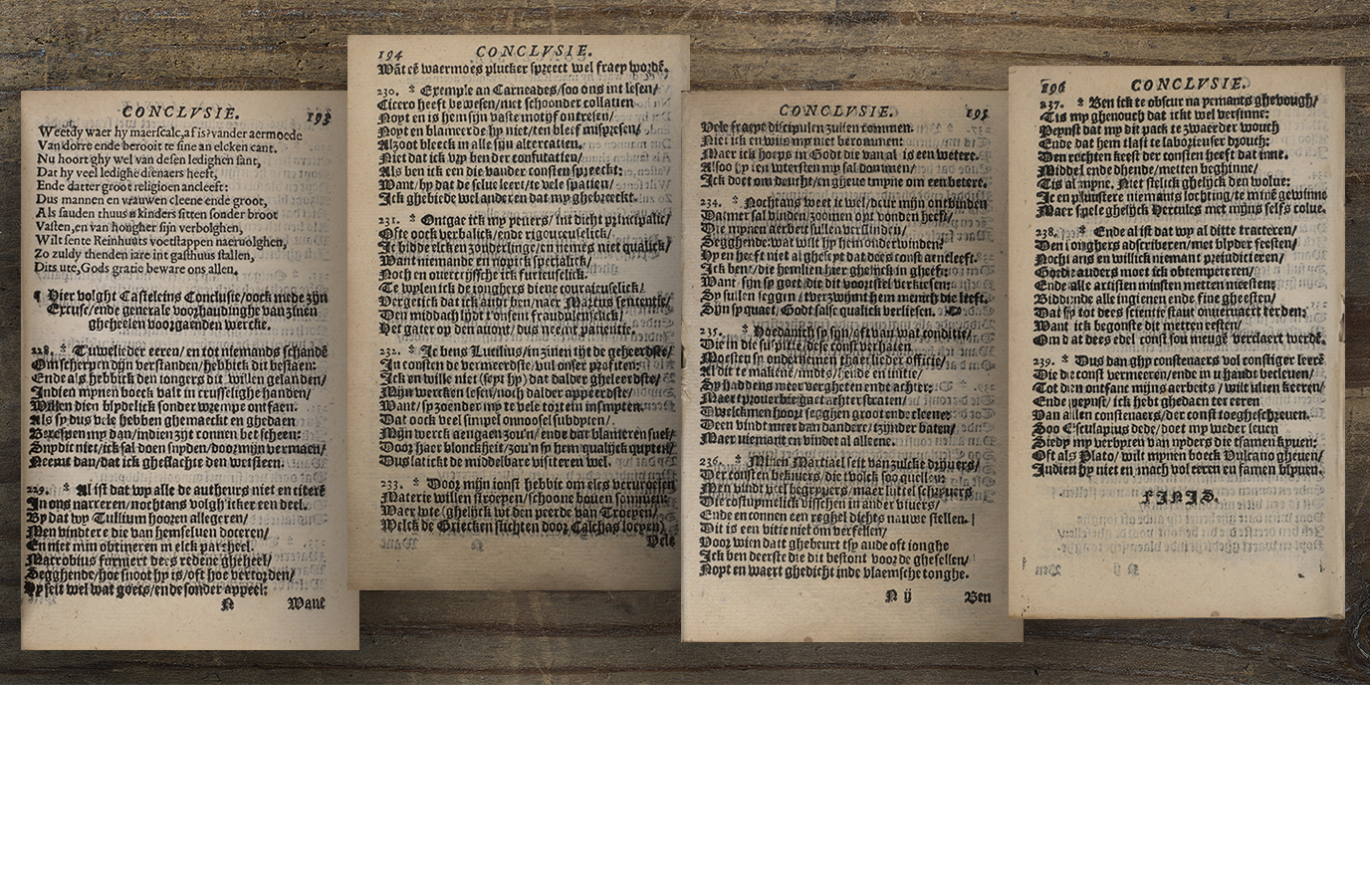

One well-known factor was Matthijs de Castelein. As the literary leader of two chambers, Pax Vobis (Peace to You) and De Kersauwe (The Daisy), he wrote De Const van Rhetoriken (The Art of Rhetoric) (1555), the first (and only) manual for rhetoricians.[3] In 239 stanzas De Castelein explains the ‘art of rhetoric’ to ‘all beginners and enthusiasts’ and writes about the practicable forms of poetry and drama, providing examples, instructions and possible subjects that poets can use. His book is based on Jean Molinet’s L’art de rhétorique, the Flemish rhetorician tradition and the classical authors, in particular Quintilian, Cicero and Horace.[4]

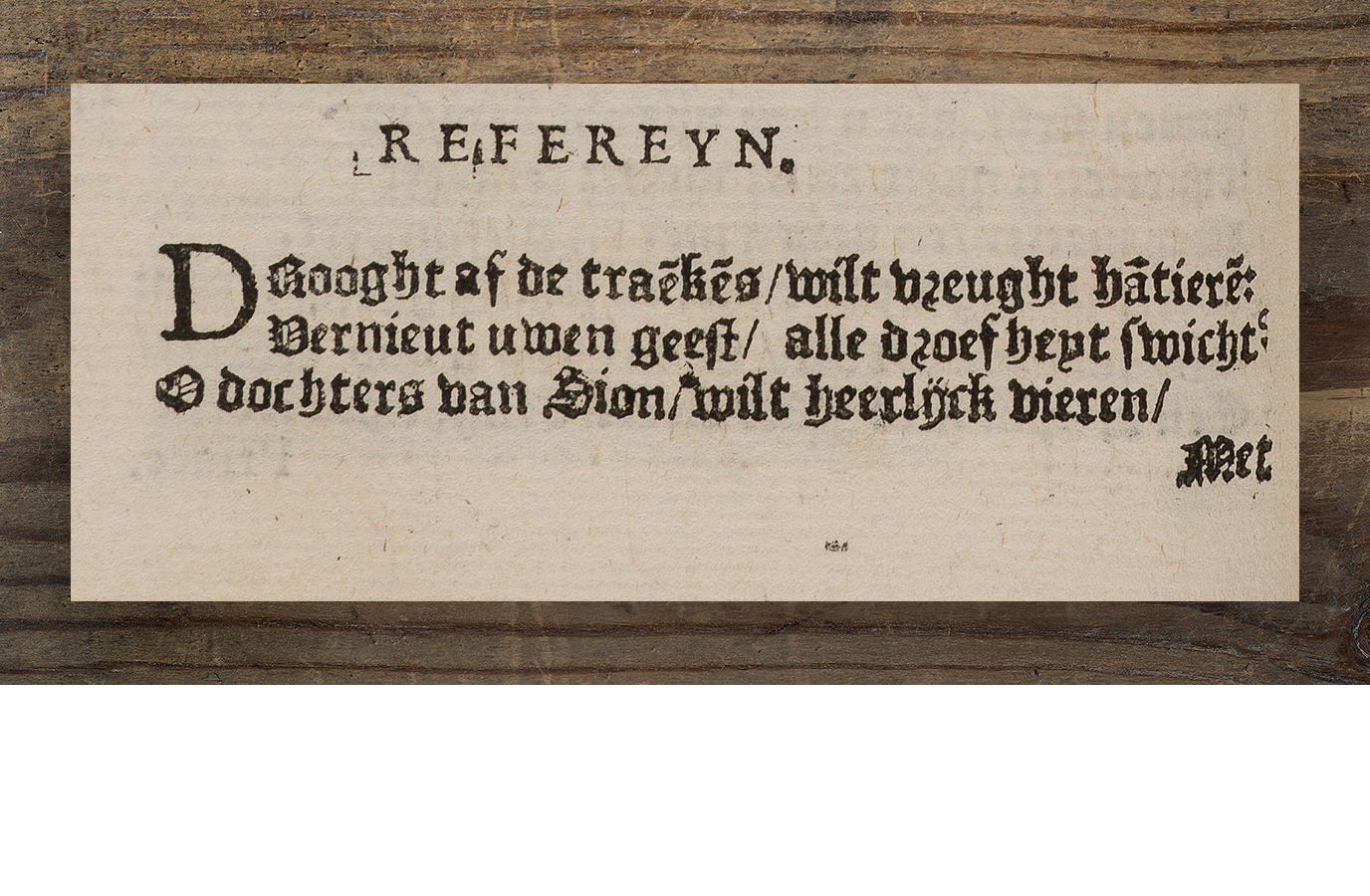

The refrain

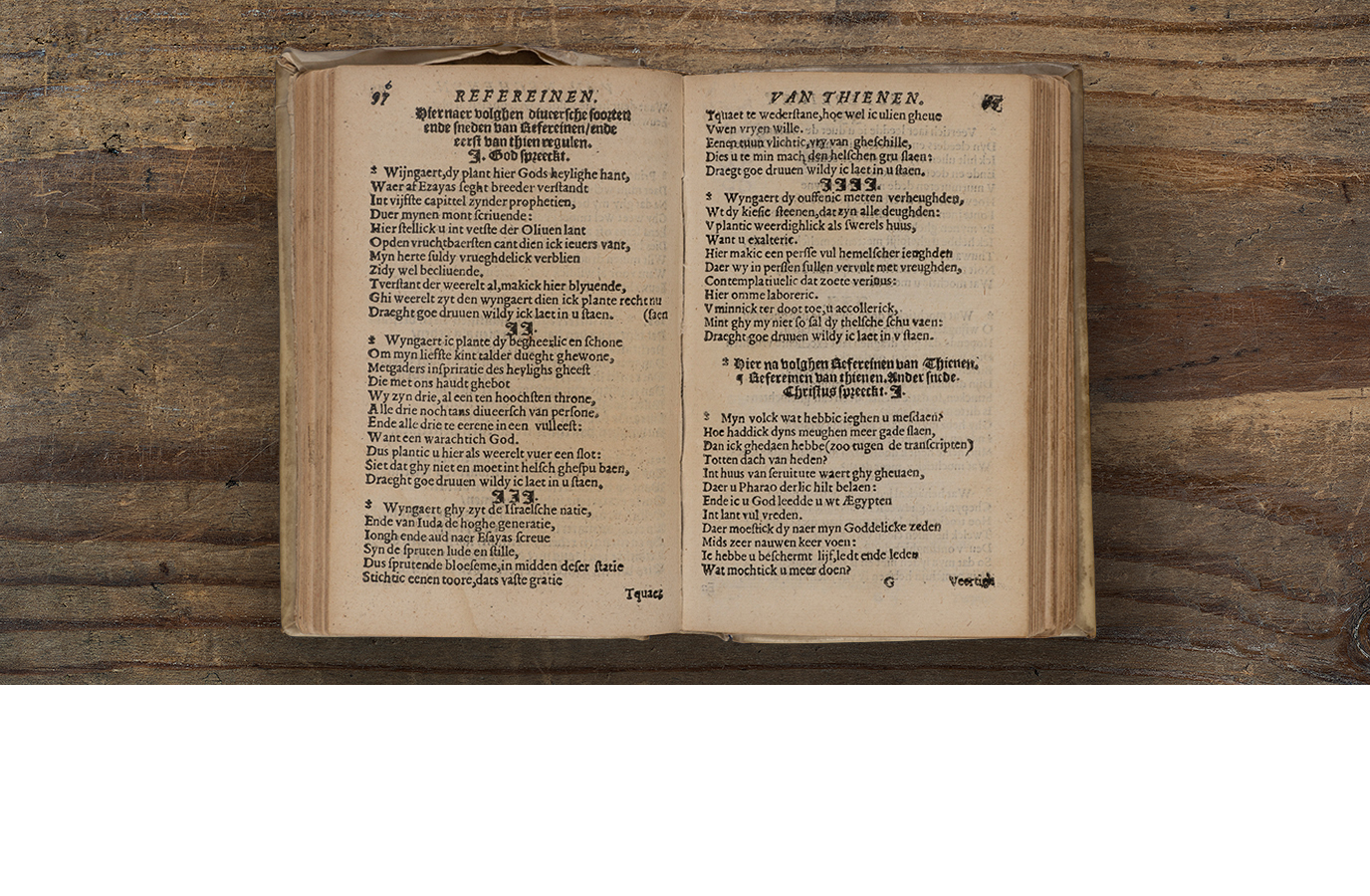

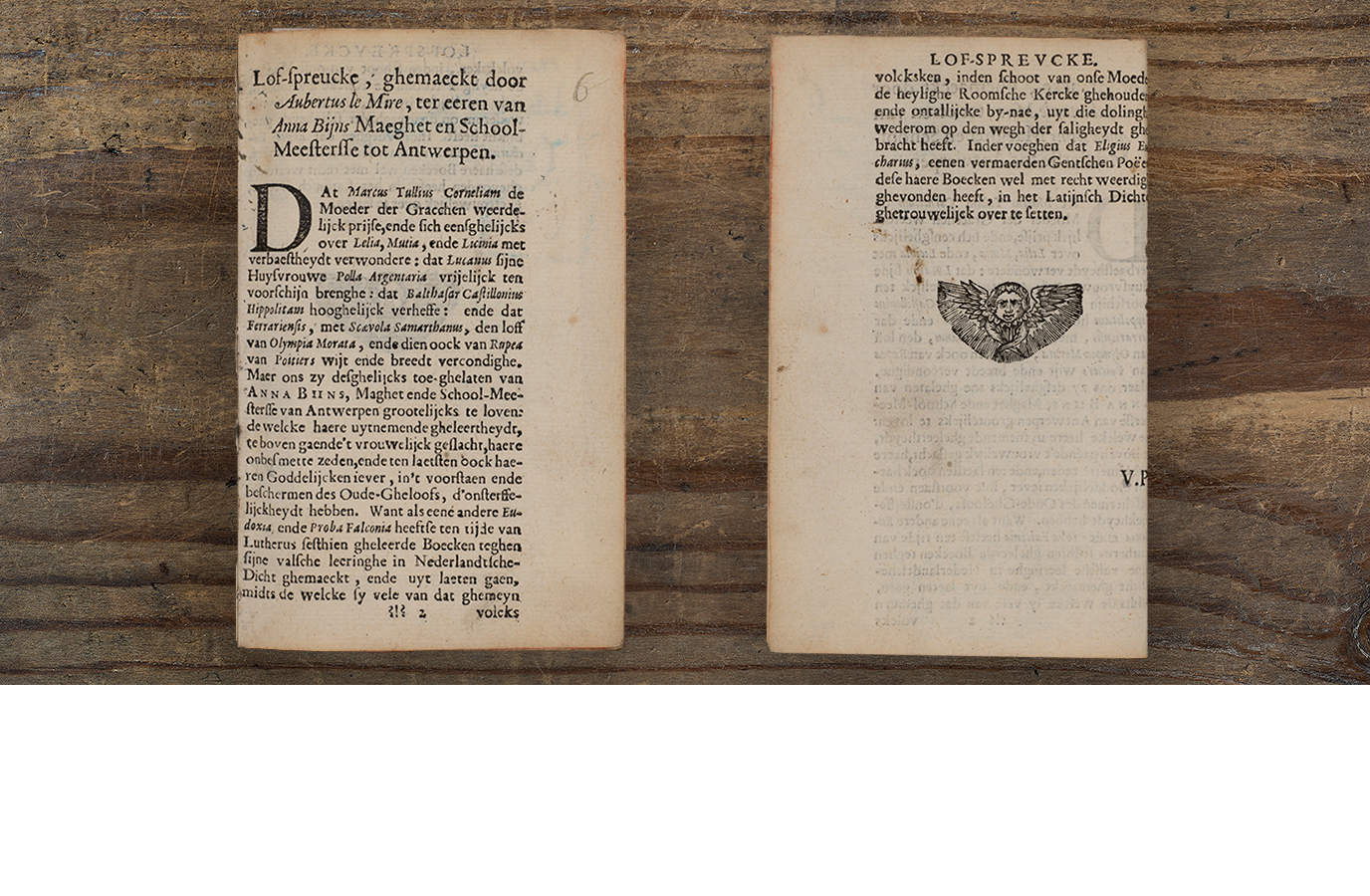

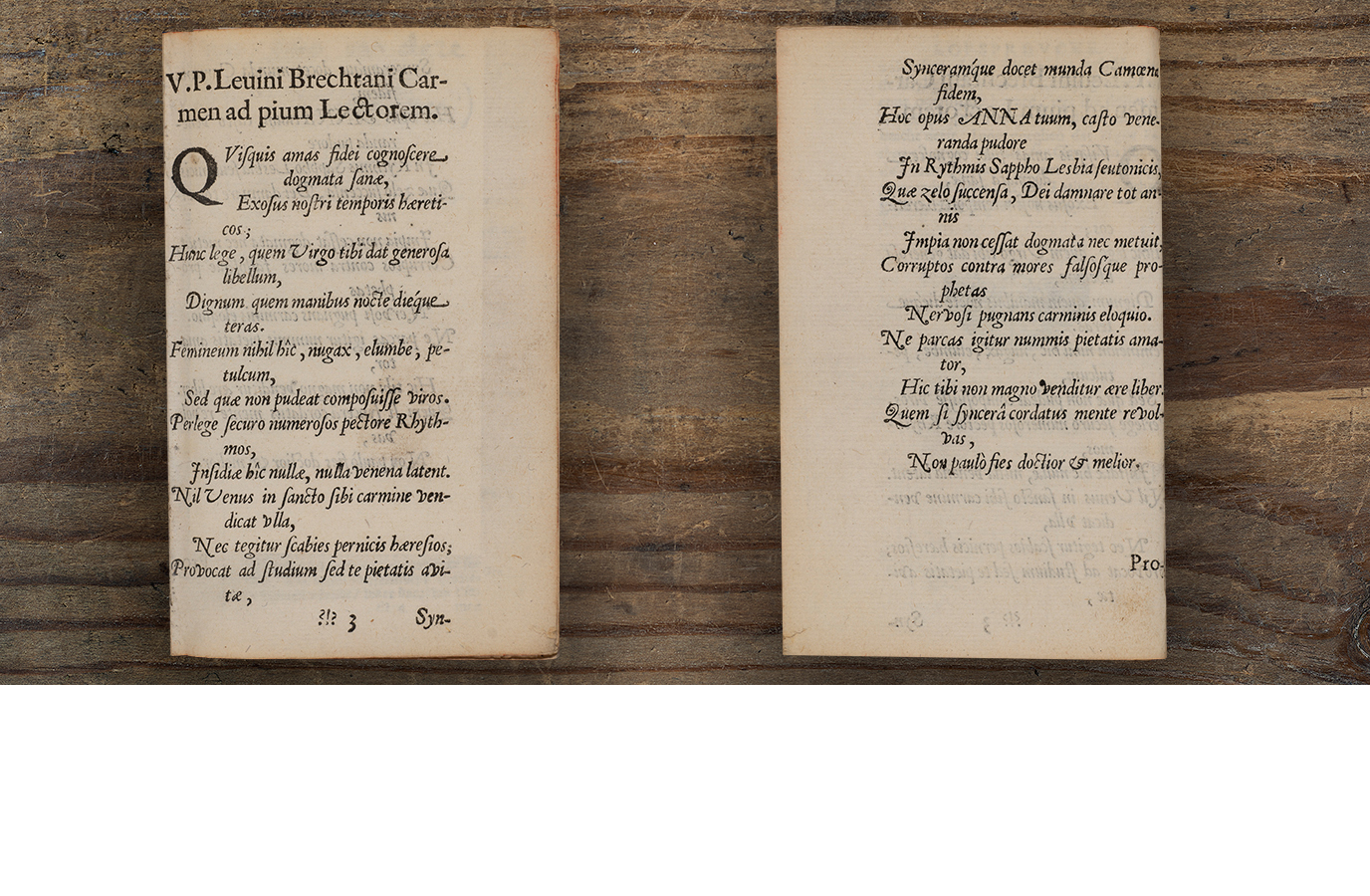

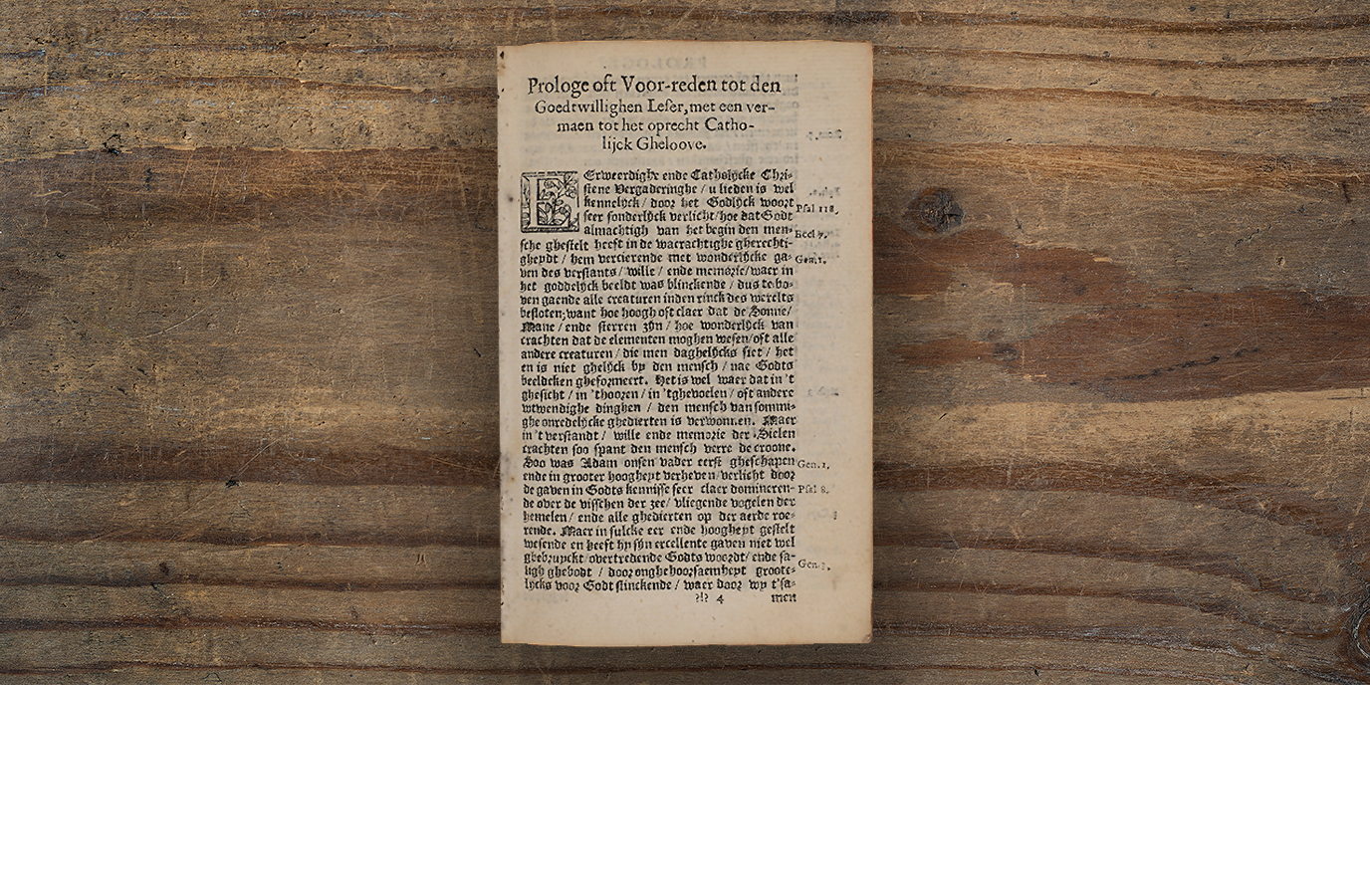

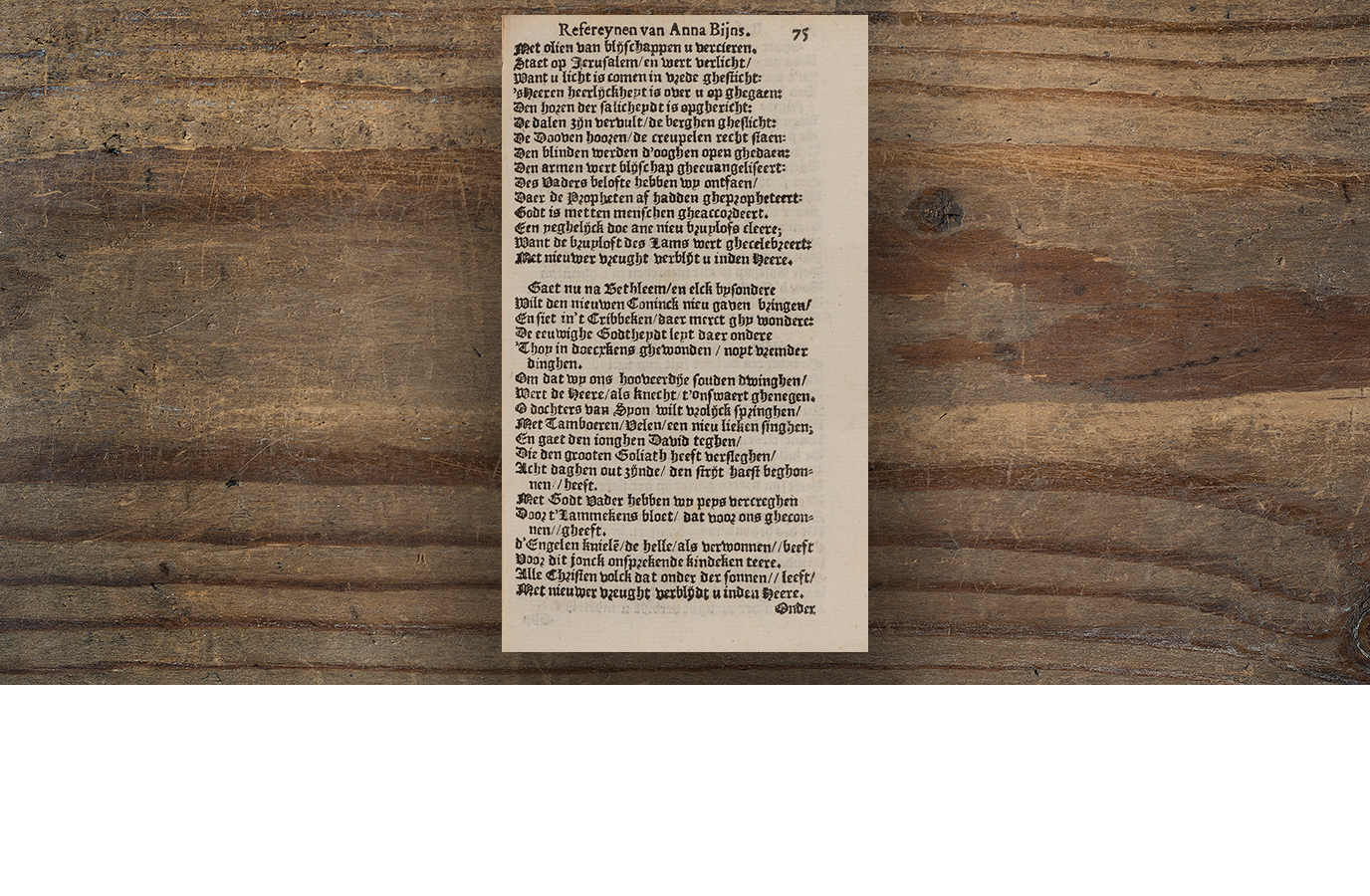

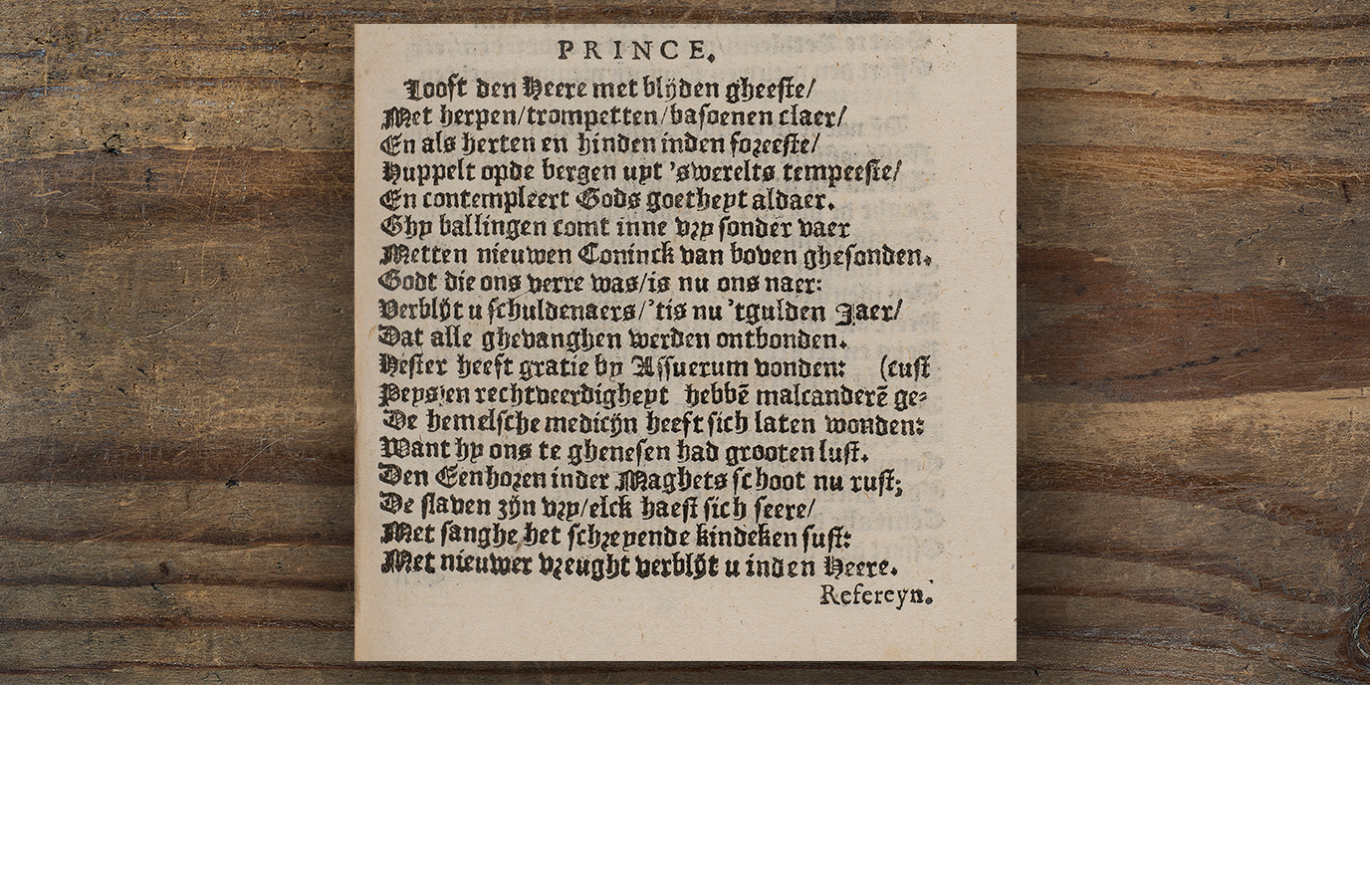

A popular genre among the rhetoricians was the refrain: a poem consisting of four or more stanzas, all of which end with one or two identical lines, referred to as the stok or refrain. The last verse was usually dedicated to the prince of the chamber and was therefore also known as the prince stanza. A special writer of refrains was the Antwerp teacher Anna Bijns. The South Netherlandish poet founded her own school, Het Roosterken, where she taught until 1573. Bijns wrote poetry in the style of the rhetoricians, but because she was a woman she could not become a member of a chamber. However, she is regarded as a rhetorician.

Bijns was against the Reformation and supported the Catholic church. Her refrains were printed thanks to her contacts with Antwerp Franciscans and her views on the Reformation – in other words, thanks to the approval of Divine authorities.[6] Anna Biins Konstighe Refereynen (Anna Biins's Artistic Refrains) (1646), a volume of refrains published posthumously, can be consulted in the Special Collections’ reading room. The book does not only provide a picture of her extensive oeuvre, but also of female authorship and the religious war of the sixteenth century.

A burly farce

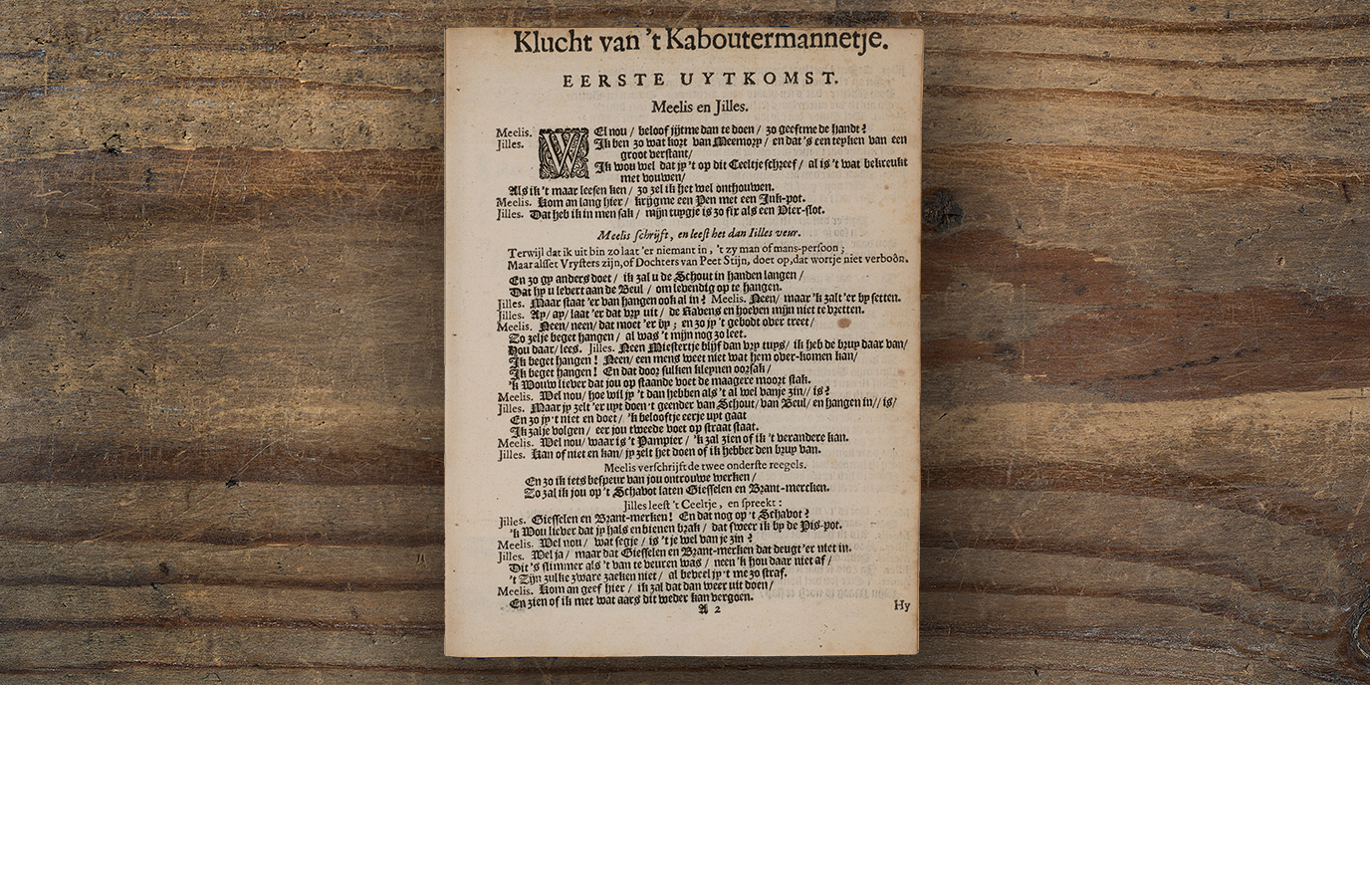

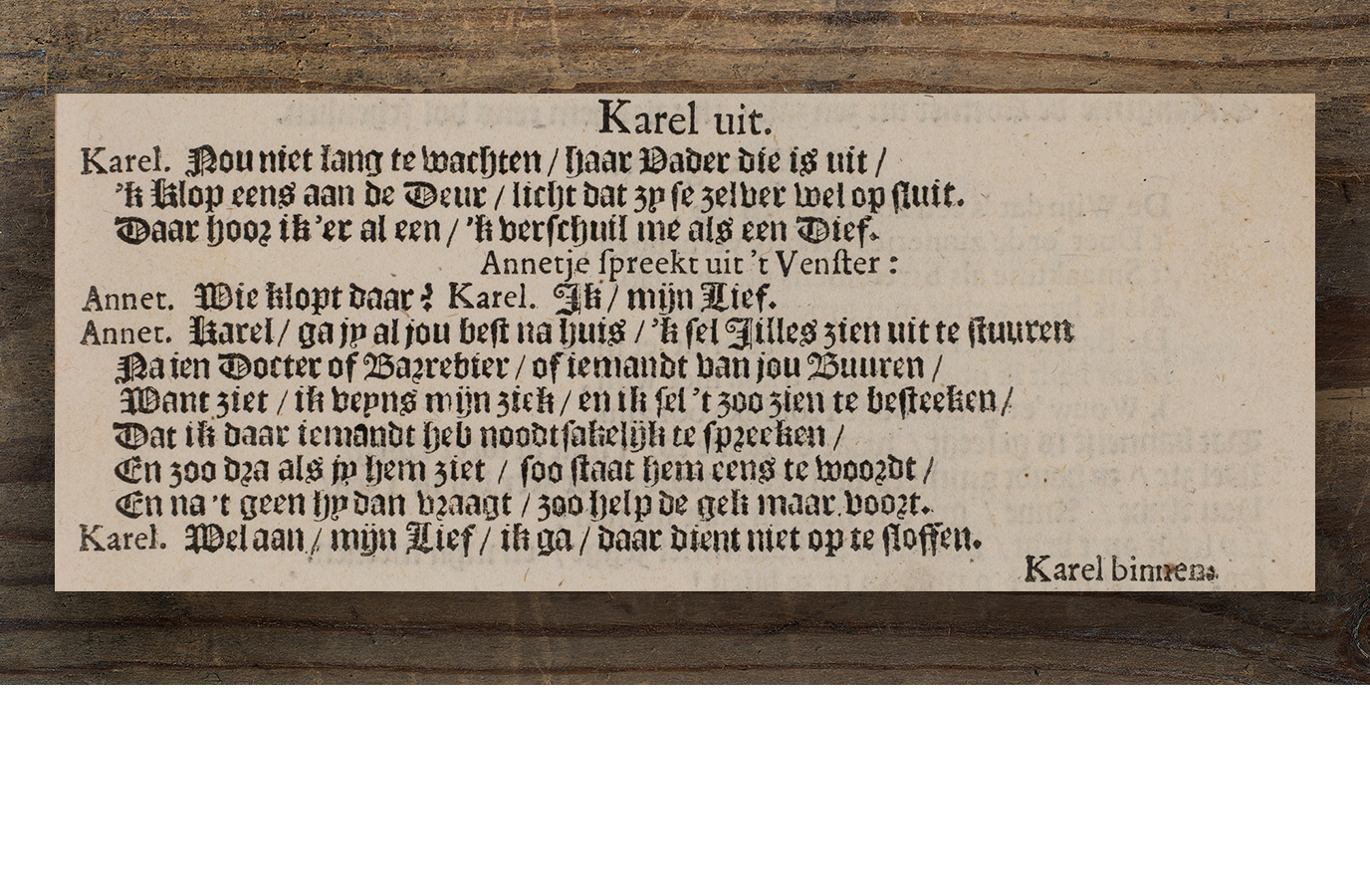

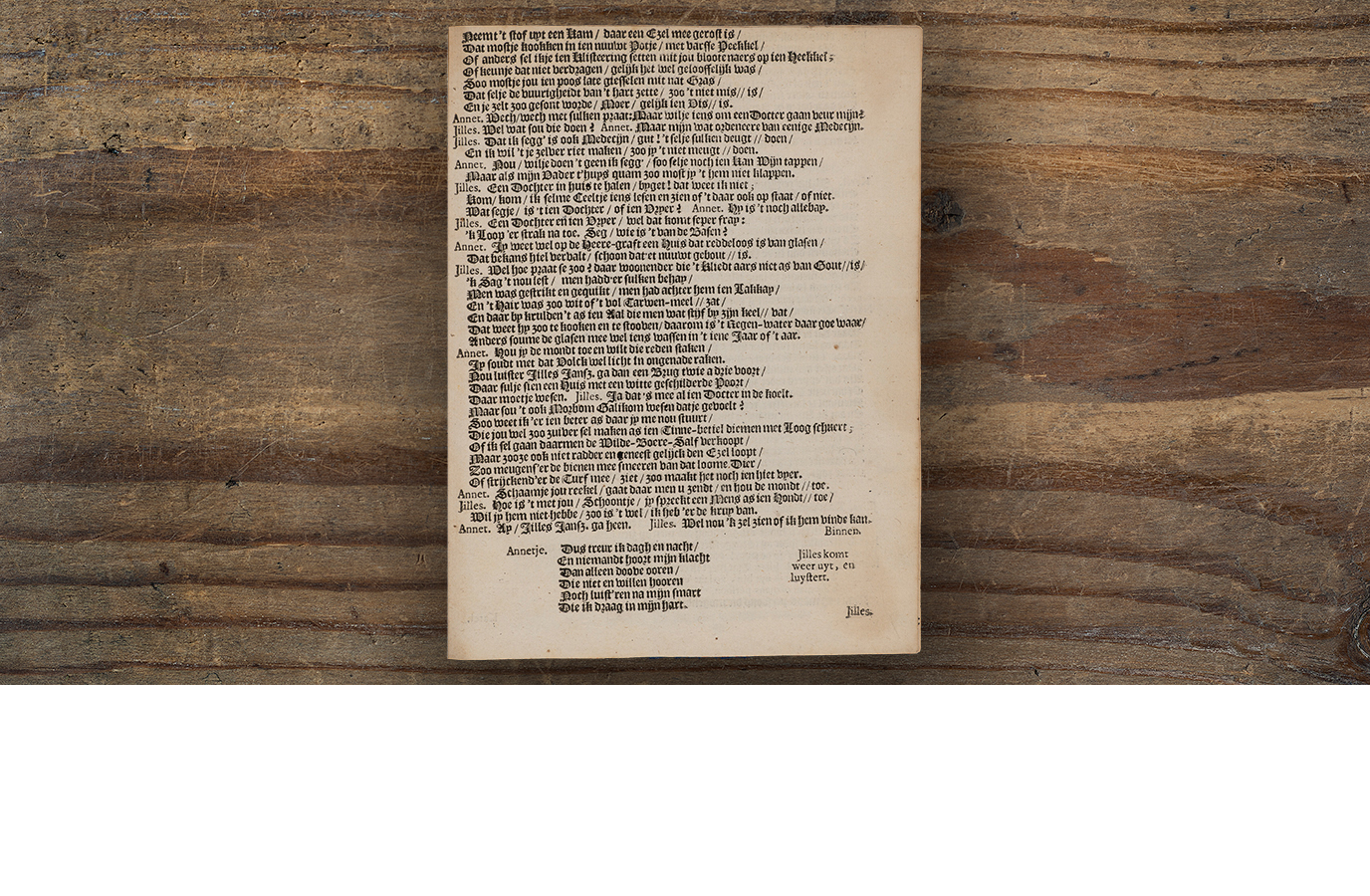

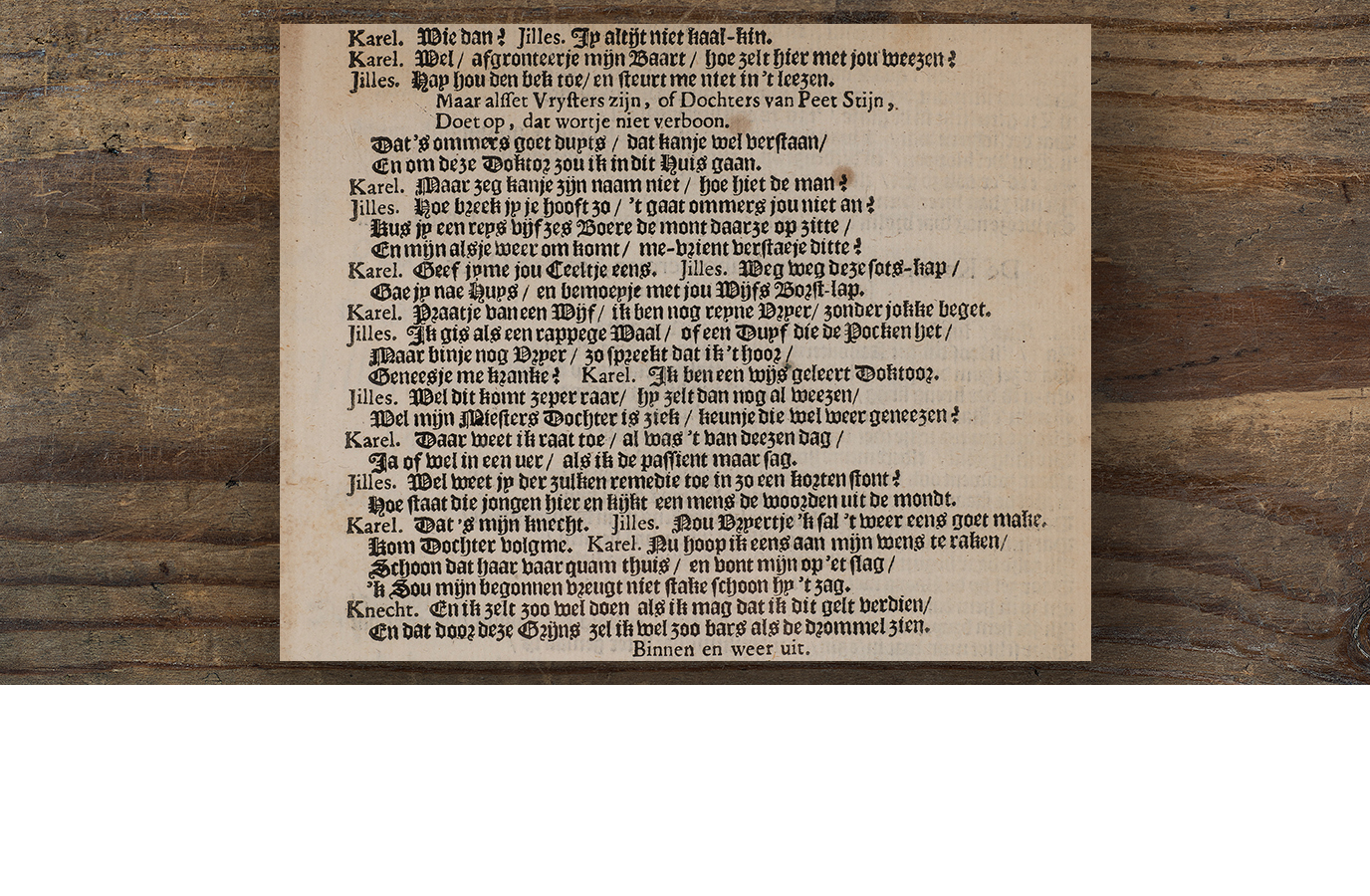

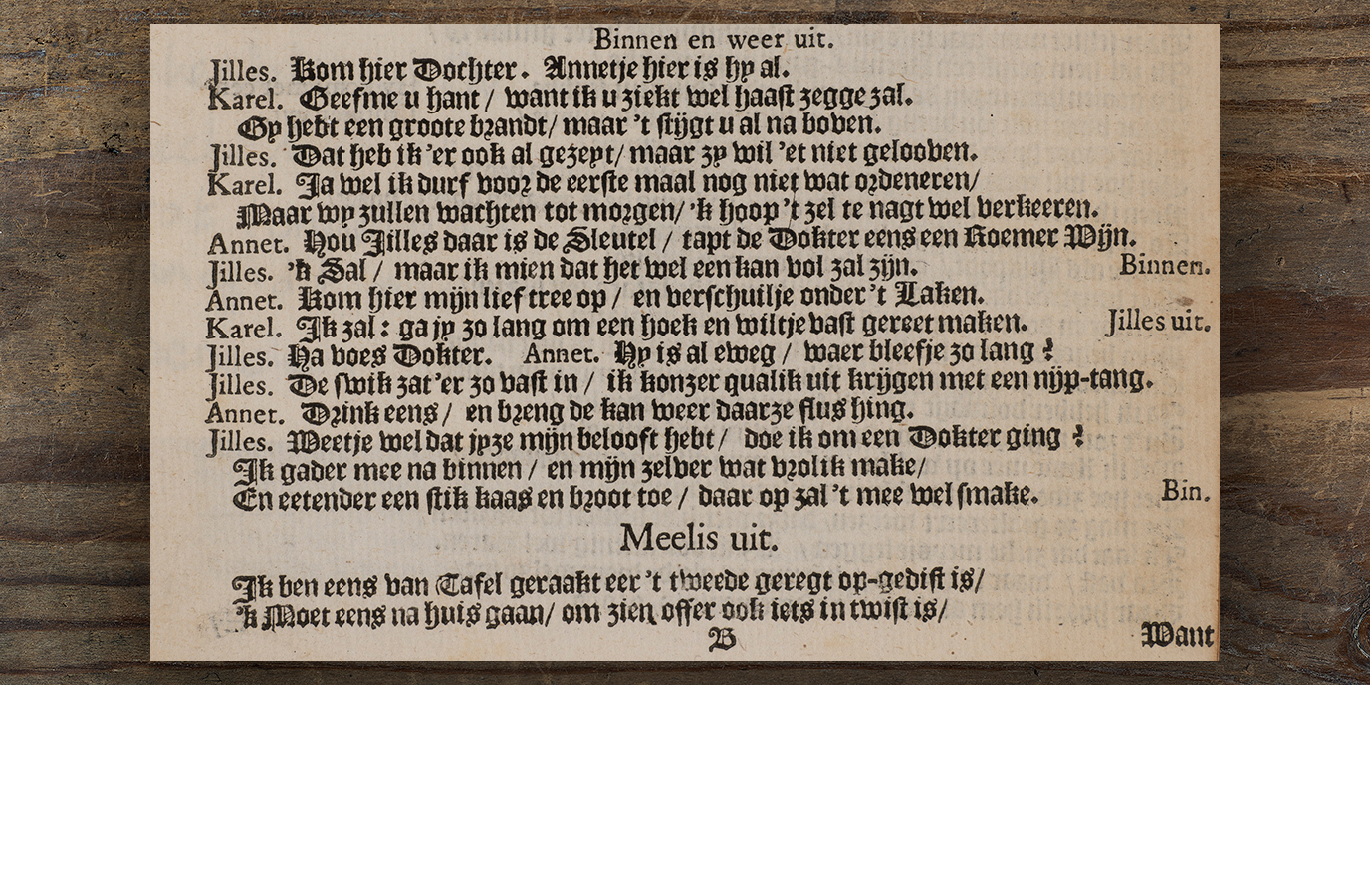

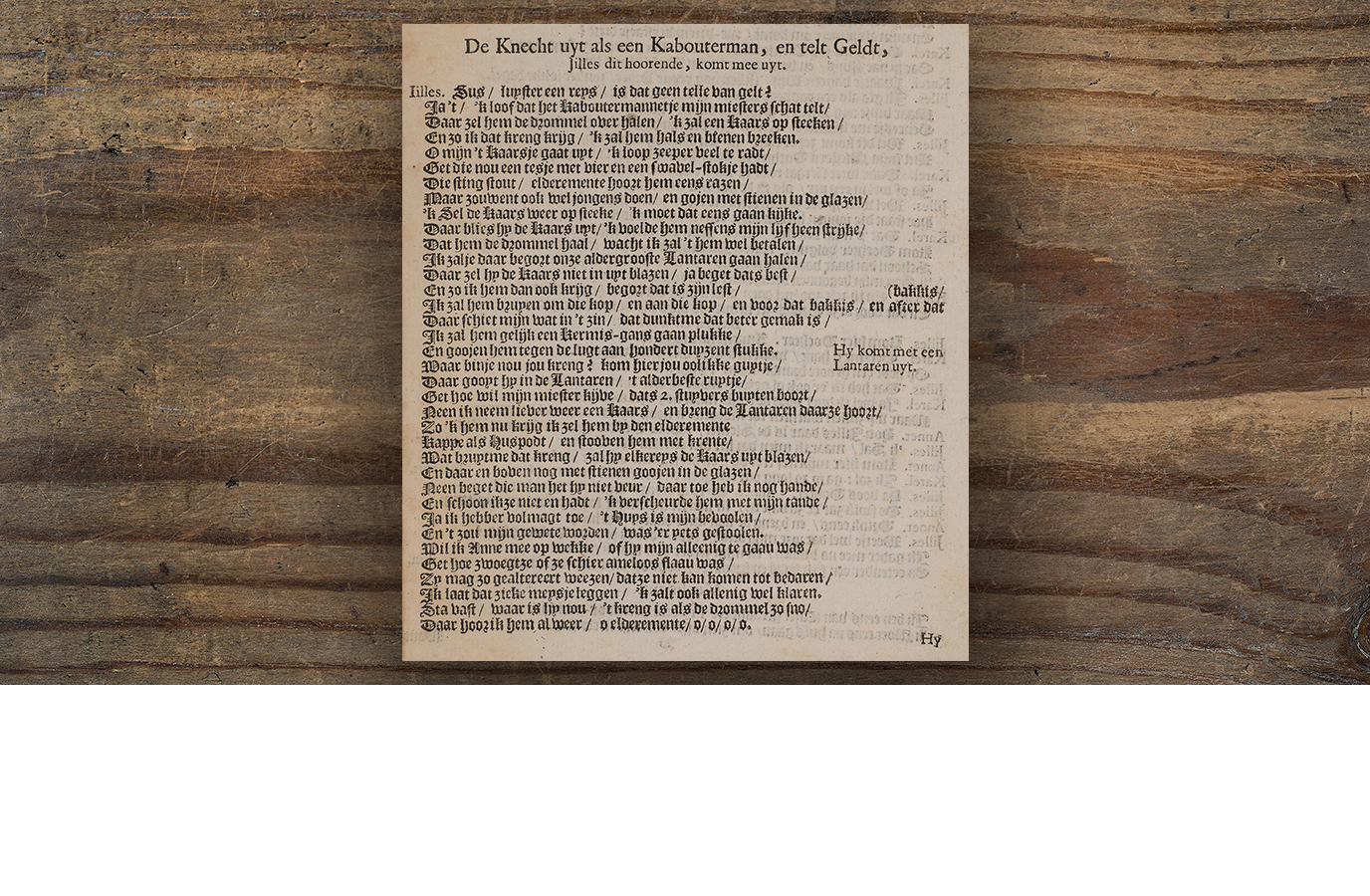

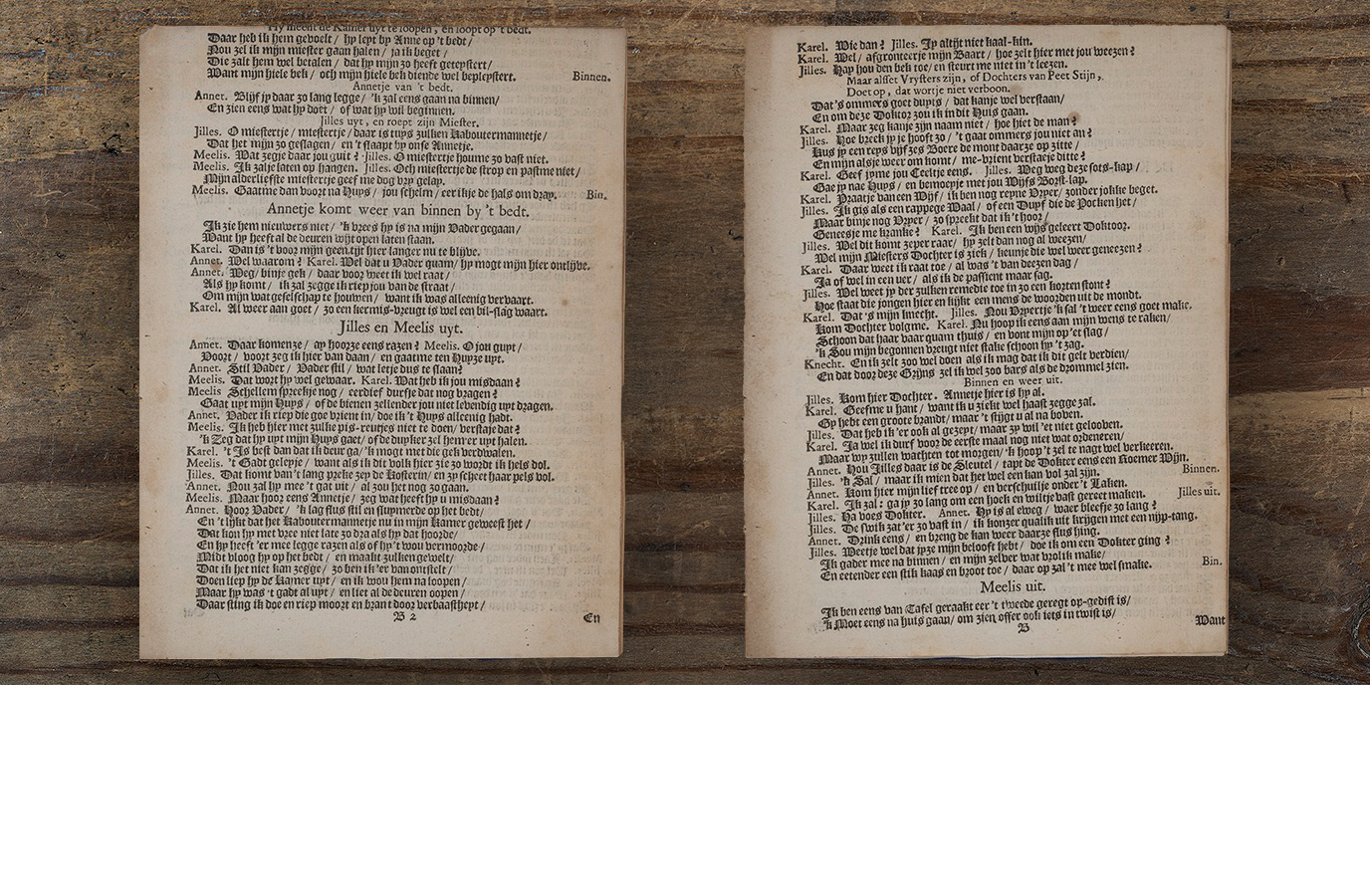

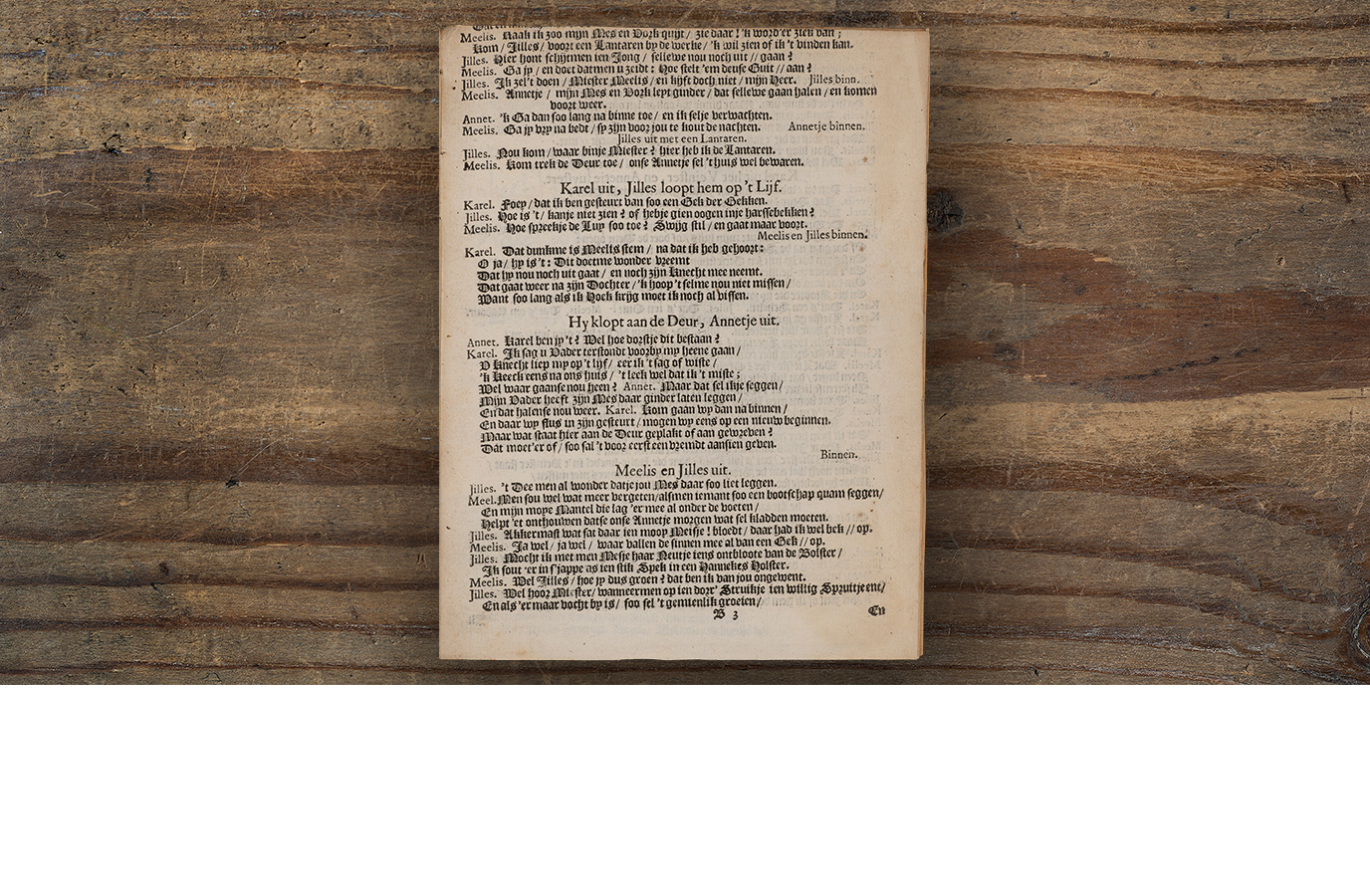

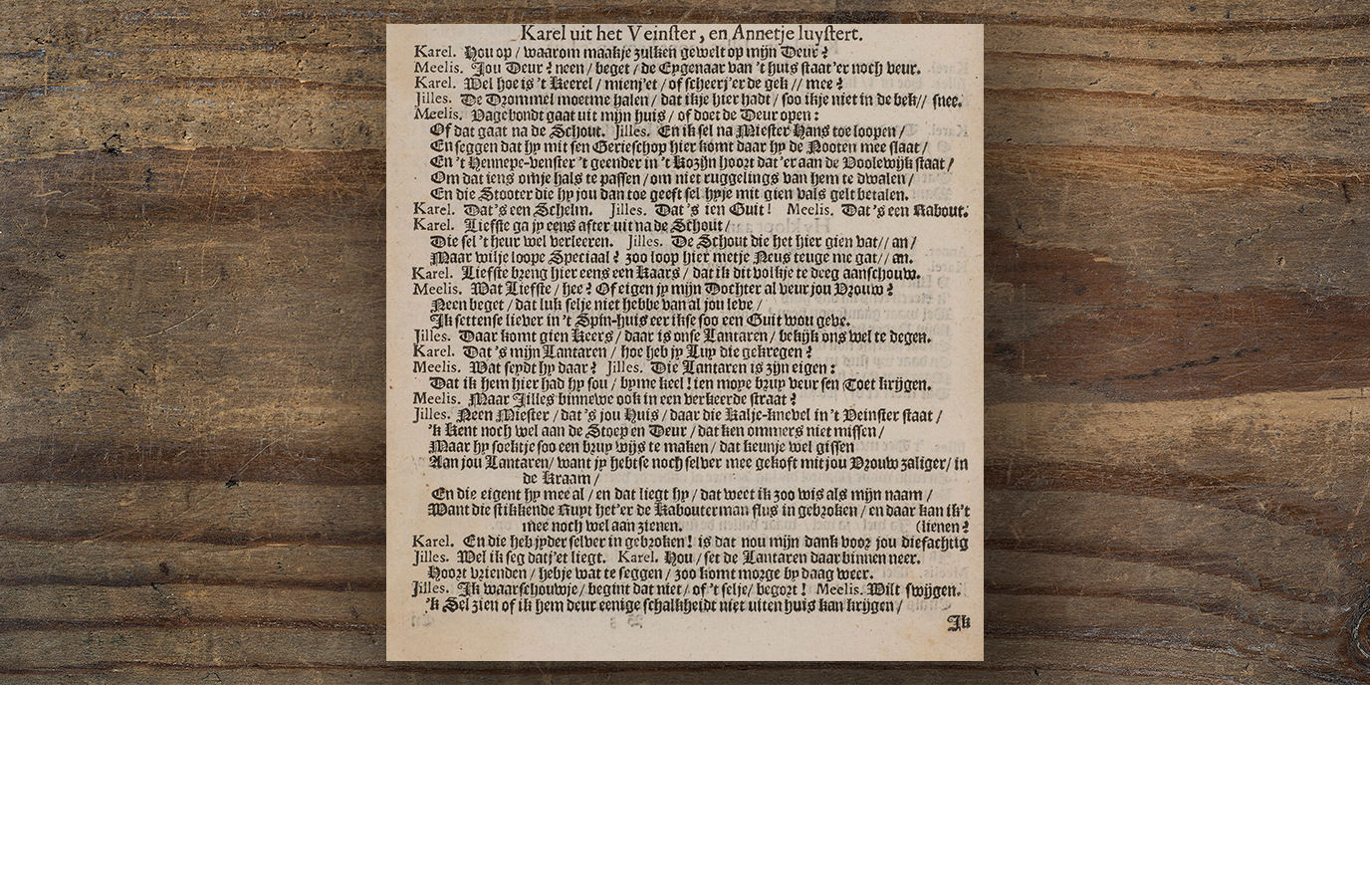

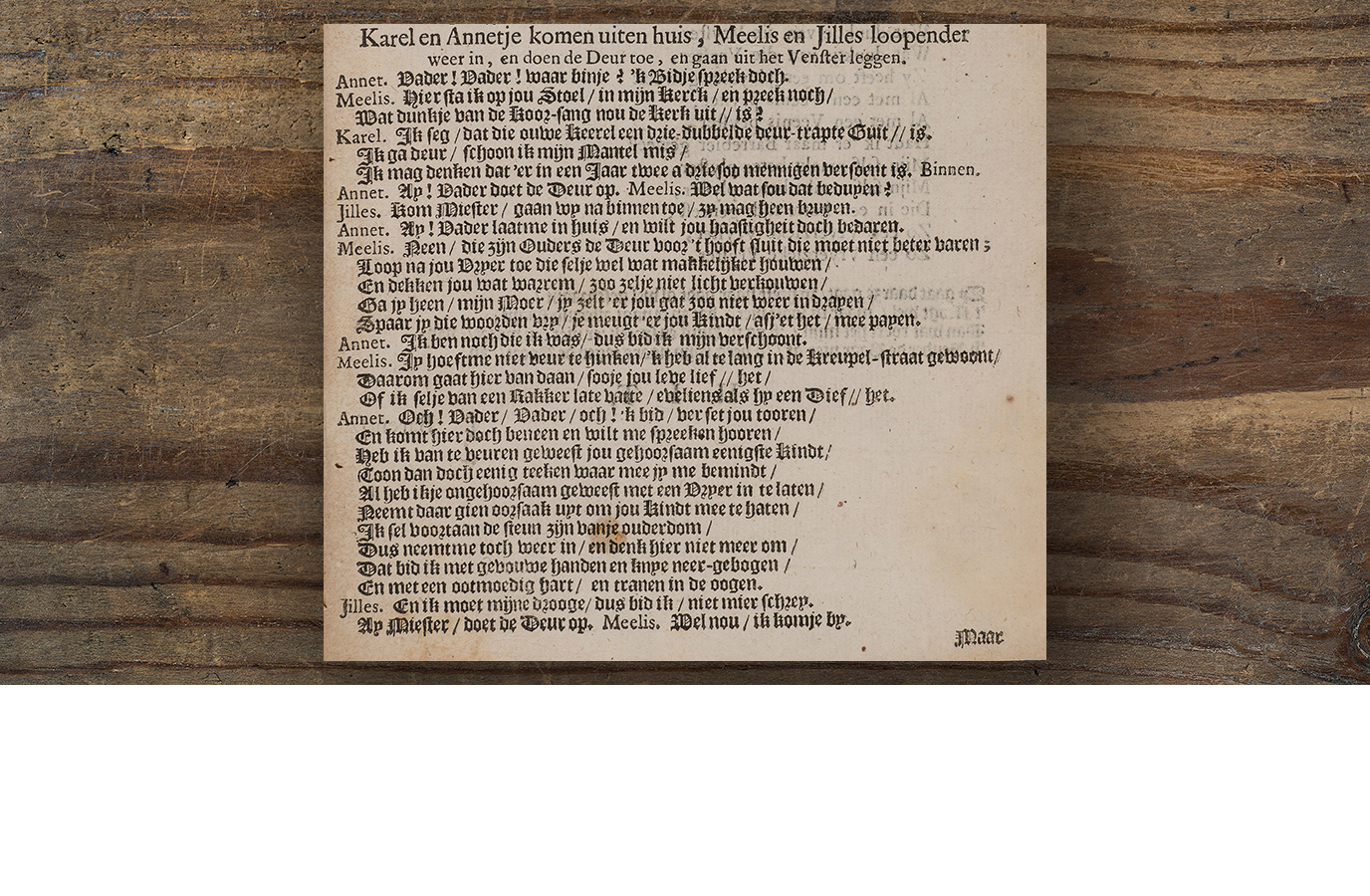

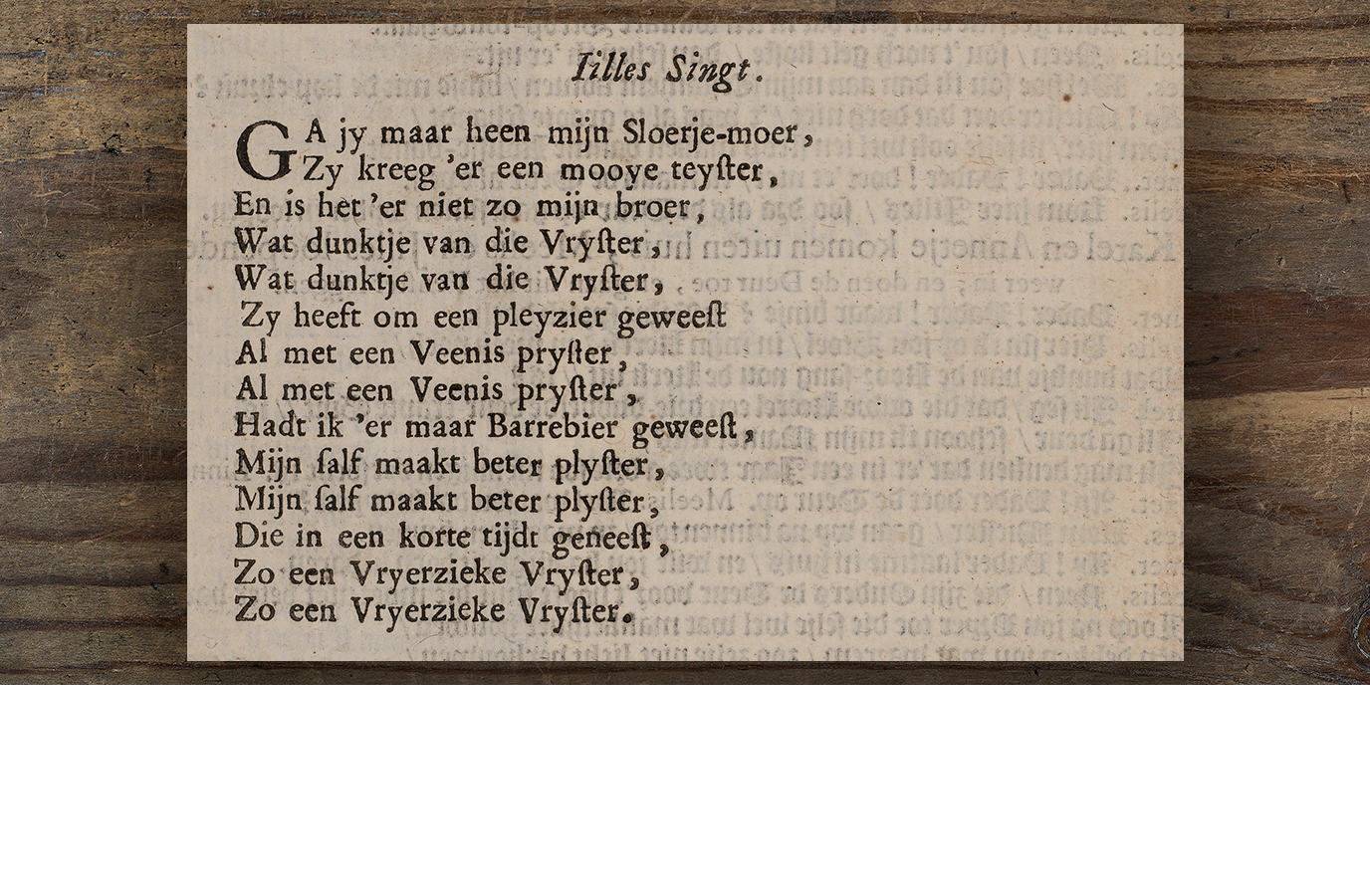

Quick, comical and caricaturing. The farce was a very popular genre among the rhetoricians. A farce is a short play with a simple plot. The characters are usually caricatures and the play is often about excess or deceit. The farces of the rhetoricians regularly criticized society and were consequently crammed with satirical elements.[10] A farce was written to make people laugh and in the seventeenth century it was the most commonly performed kind of comic theatre in the Dutch Republic.[11] In the Klucht van Buchelioen ’t Kaboutermannetge (Farce of Buchelioen the Gnome) (1655), coarse dialogues and cunning events alternate seamlessly. Deceit plays a major role: daughter Annetje misleads her unsuspecting father and his naive servant. Ultimately all three fall victim to her tricks. An extensive overview of the content of the farce can be found in the slide show below.

Morality

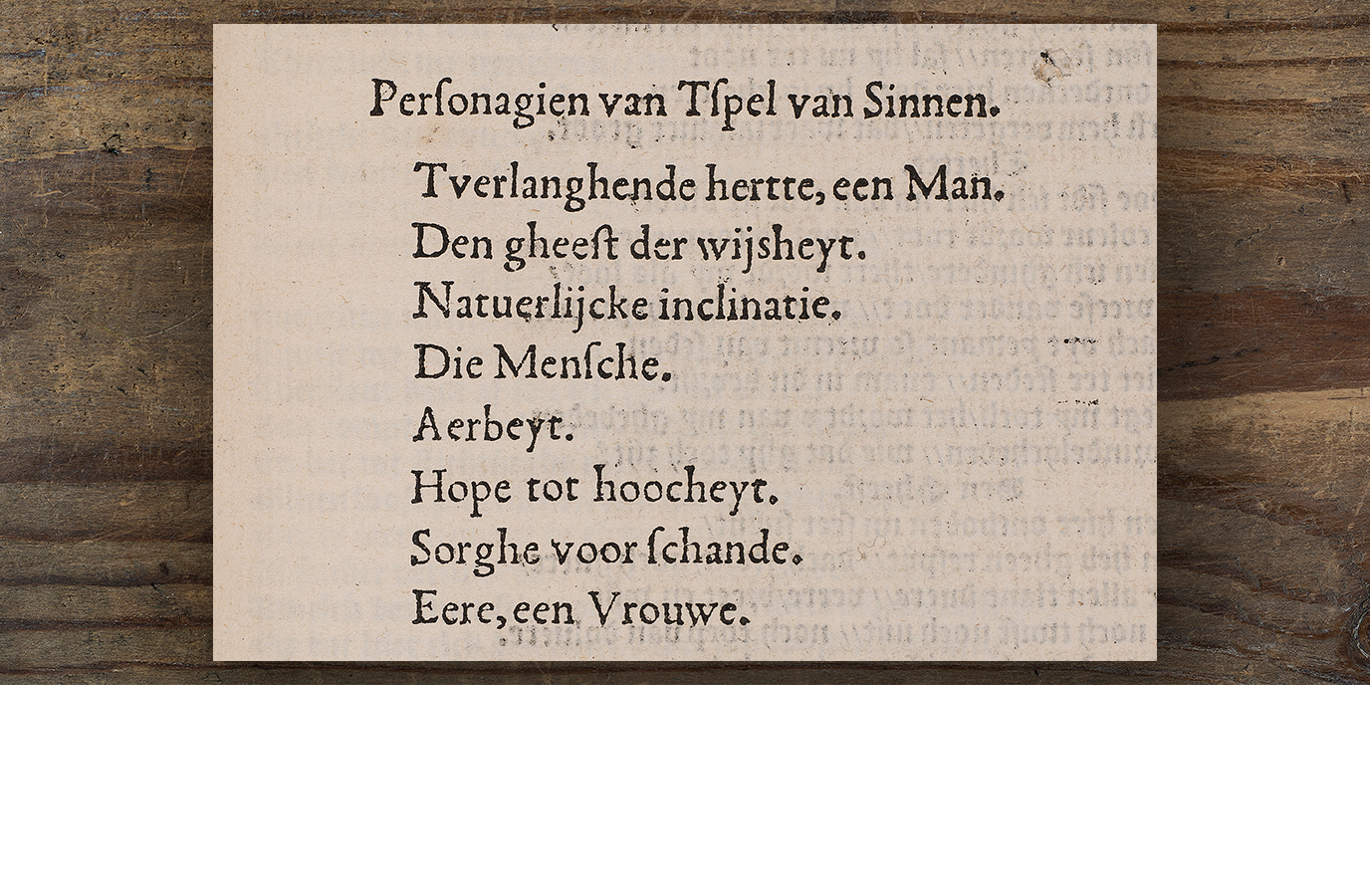

Like the refrain and the farce, the morality play was a favourite among the rhetoricians. The moralistic message (zin) of this didactic genre summarizes the idea of the play as a whole. The morality play is an allegorical drama in which qualities or attributes are personified. In the sixteenth century, concepts such as ‘Faith’, ‘virtue’, ‘truth’ and ‘light’ usually appeared as characters on the stage. The most popular personifications were those known as sinnekens: devilish figures which try to mislead the protagonist. Many morality plays were written for and performed during competitions. Most of these were held between chambers from one region or province.

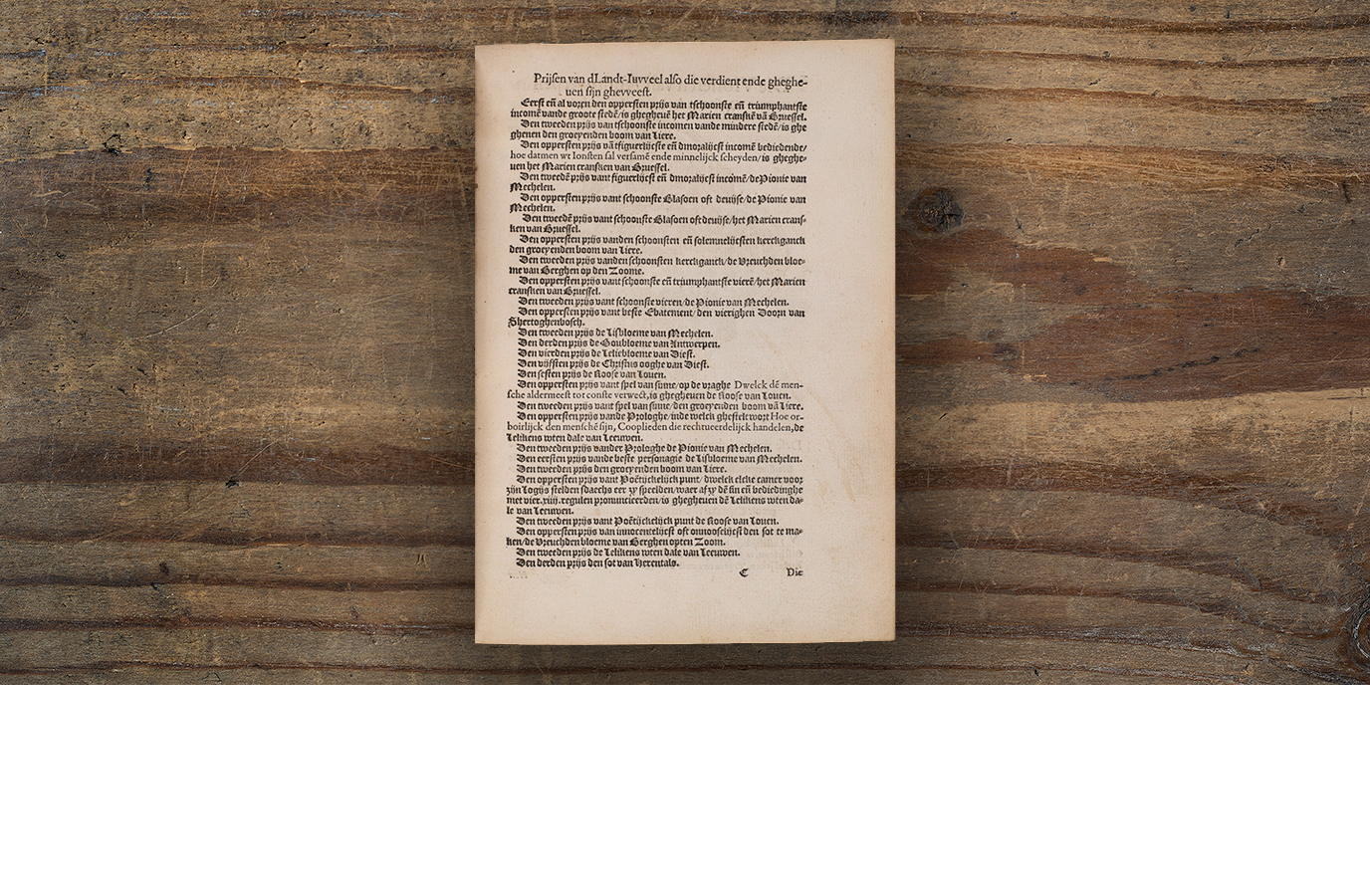

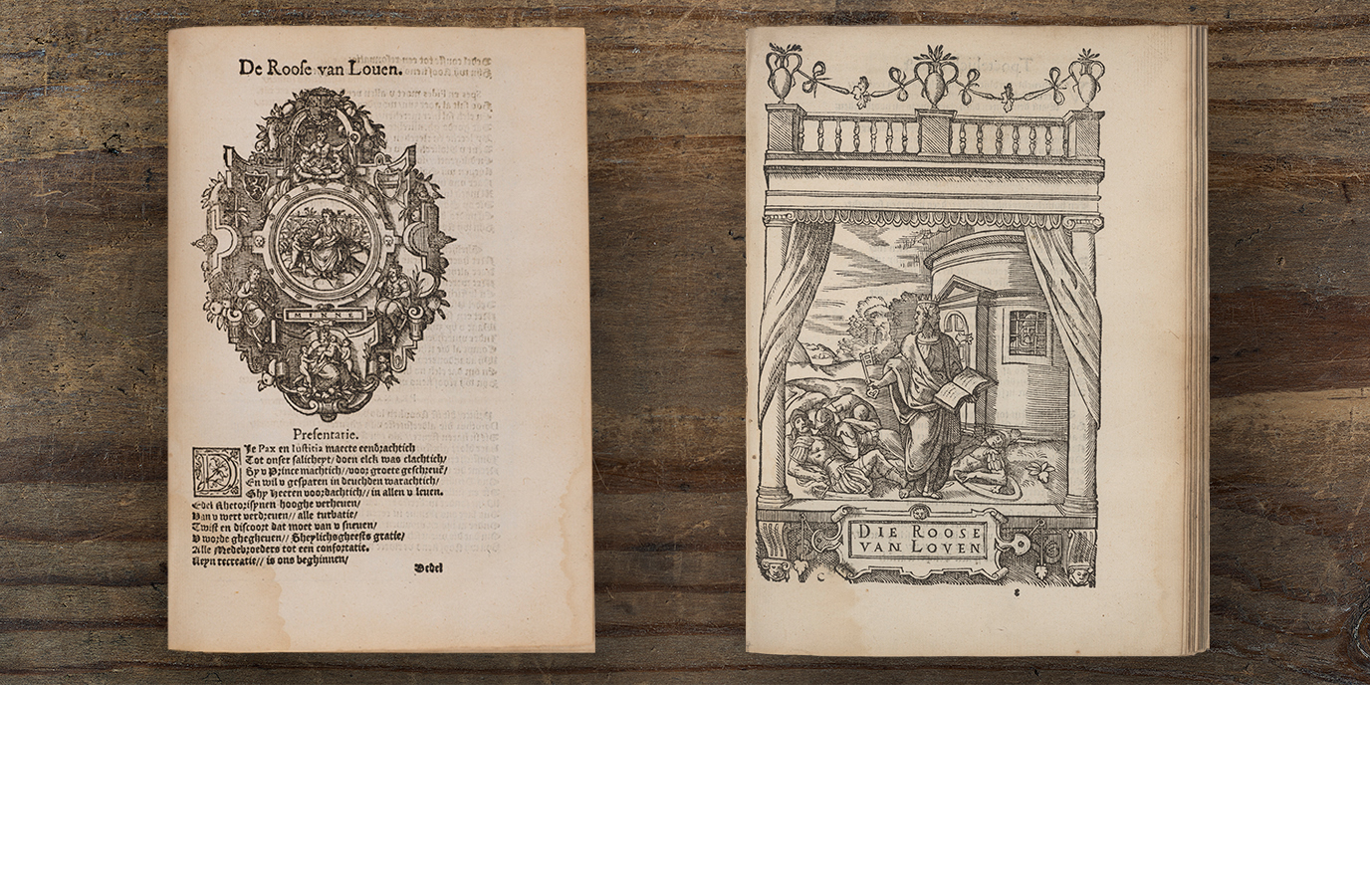

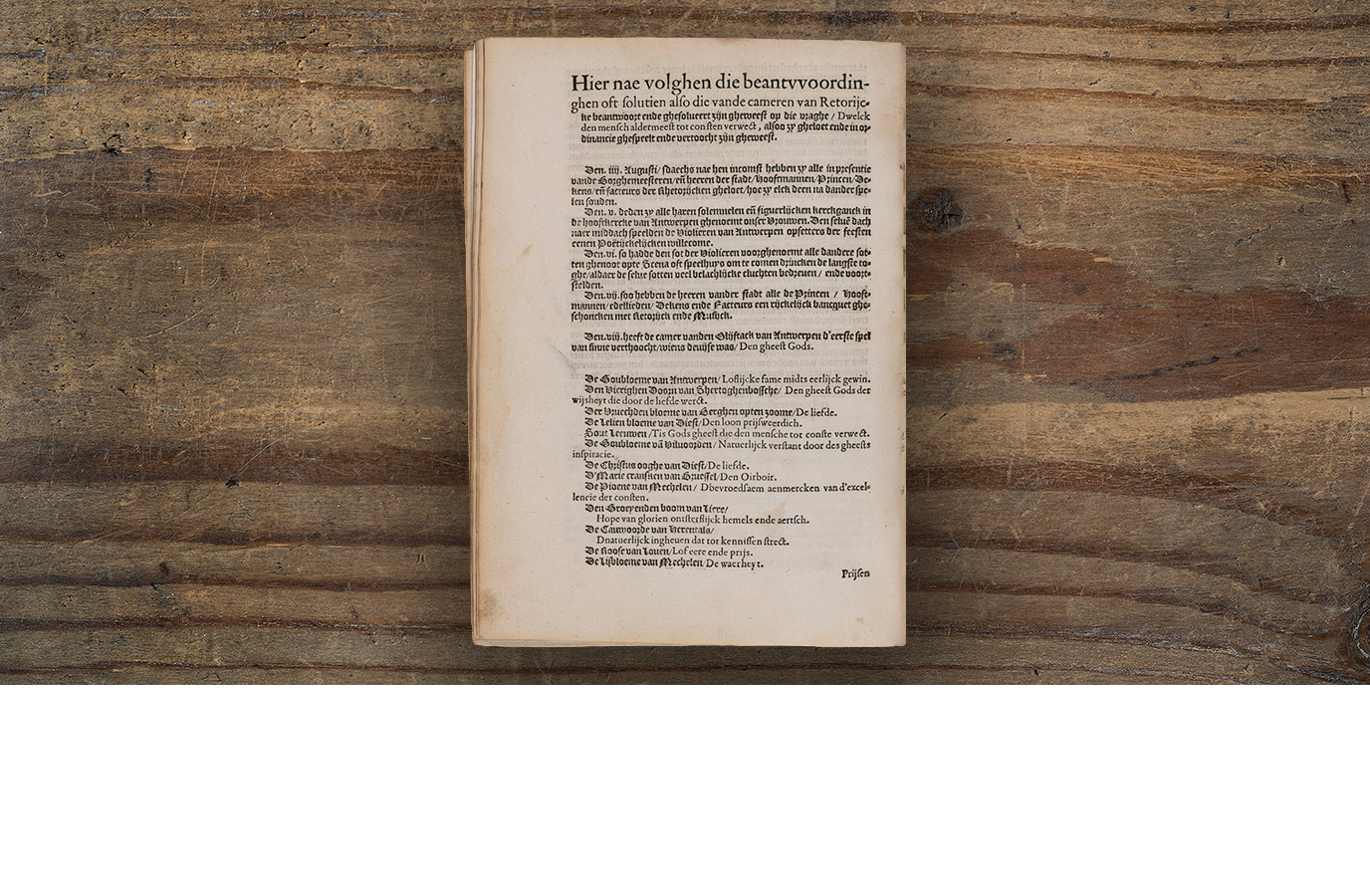

The most famous example of such a competition is the Antwerp Landjuweel of 1561, in which fourteen chambers of rhetoric from Brabant competed. This competition was organised by the local chamber De Violieren (The Gillyflowers). The festivities lasted no less than a fortnight, had an estimated 5,000 participants and took place mainly outdoors. This Antwerp Landjuweel is known as the biggest competition ever held by the rhetoricians. Spelen van sinne vol scoone moralisacien vvtleggingen ende bediedenissen op alle loeflijcke consten (Morality plays filled with morals, explanations and meanings) (1562) contains the poems recited and plays performed at the Landjuweel of Antwerp. Competition volumes of this kind provide a unique insight into the world of the sixteenth-century rhetoricians.

Thanks to their own hard work and good record keeping, the rhetoricians have left us a magnificent and extensive oeuvre. The products of the rhetoricians are of priceless value. Their literature offers us not only an understanding of the literary world but also of personal, religious, social and political life between the middle ages and the modern era. Would you like to see more of their repertoire? Take a look at the list of the rhetoricians’ collection of Special Collections.

Literature

[1] Herman Pleij. Het gevleugelde woord. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1400-1560. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2007.

[2] Bart Ramakers, red. Confirmisten en rebellen. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003.

[3] Dirk Coigneau. “Matthijs de Castelein: ‘excellent poëte moderne.’” In Verslagen en Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Academie Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde (1985): 451-475.

[4] Matthijs de Castelein. De Konst van Rhetoriken. Rotterdam: Felix van Sambir, 1612. uklu 'EP'EP E 242. Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen.

[5] G.J. van Bork en P.J. Verkruijsse. “Castelein, Matthijs de.” In De Nederlandse en Vlaamse auteurs. Van middeleeuwen tot heden. Weesp: De Haan, 1985.

[6] Orlanda S.H. Lie. “Middelnederlandse literatuur vanuit genderperspectief. Een verkenning.” In Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal en Letterkunde 117 (2001): 246-267.

[7] G.J. van Bork en P.J. Verkruijsse. “Bijns, Anna.” In De Nederlandse en Vlaamse auteurs. Van middeleeuwen tot heden. Weesp: De Haan, 1985.

[8] Herman Pleij. Anna Bijns van Antwerpen. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2011.

[9] Anna Biins Konstighe Refereynen. Antwerpen: Hieronymus Verdussen den Jonghere, 1646. uklu A 6558. Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen.

[10] Karel Porteman & Mieke B. Smits-Veldt. Een nieuw vaderland voor de muzen. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1560-1700. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2008.

[11] W.A. Ornée. “Het kluchtspel in de Nederlanden, 1600-1760.” In Scenaríum 5 (1981):107-120.

[12] Jan Barentsz. Klucht van Buchelioen ’t Kaboutermannetge. Amsterdam: Dirck Cornelisz. Houthaak, 1655. uklu 'EP'EP E 198. Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen.

[13] Arjan van Dixhoorn. Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Noordelijke Nederlanden 1400-1650. DBNL, 2004. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/dixh002repe01_01/.

[14] Jeroen Vandommele. Als in een spiegel. Vrede, kennis en gemeenschap op het Antwerpse Landjuweel van 1561. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2011.

[15] Spelen van Sinne. Antwerpen: M. Willem Silvius, 1562. uklu 'EP'EP E 244. Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen.

[16] Ruud Ryckaert. De Antwerpse spelen van 1561. Naar de editie Silvius (Antwerpen 1562) uitgegeven met inleiding, annotaties en registers. Gent: Koninklijke Academie voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde, 2011.

| Last modified: | 04 January 2021 10.29 a.m. |

![Matthijs de Castelein (Pamele bij Oudenaarde, 1485/1486 – Pamele, 1550) was a rhetorician, priest and notary. His motto was: ‘Wacht wel 'tslot, Castelein' (Guard the castle, Castle Keeper).[5] (photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl1-1.jpg)

![Anna Bijns (Antwerp, 1493 – Antwerp, 1575) grew up near the old town hall of Antwerp (see above) and worked there as a schoolteacher. Bijns’s motto was ‘Meer suers dan soets’ (More sour than sweet).[7][8] (photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl2-1.jpg)

![The preface of this seventeenth-century book is considerable. On the title page, Bijns is introduced as ‘Maiden and Schoolmistress’ – not as a poet.[9] In comparison, in "De Const van Rhetoriken" De Castelein is introduced as an ‘excellent modern poet’.](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl2-2.jpg)

![The “Klucht van Buchelioen ’t Kaboutermannetge” was written by Jan Barentsz.[12] Barentsz. was probably a member of the Amsterdamsche Kamer (Amsterdam Chamber), since the title page shows the arms of the Eerste Nederduytsche Academie (First Dutch Academy) and the motto of De Eglentier (The Sweet Briar), the two chambers from which the Amsterdamsche Kamer arose.[13]](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl3-1.jpg)

![The Antwerp chamber of rhetoric De Violieren was probably founded around 1400 as part of the powerful Guild of St Luke (the painters' guild). Their motto was ‘Wt Jonsten Versaemt’ (United in Friendship).[14]](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl4-2.jpg)

![Participation in a landjuweel was in response to a chaerte (invitation), which was sent to all the chambers in advance. This invitation included the rules of the competition as well as the subject of the morality play: ‘what most drives people towards knowledge’.[15]](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl4-3.jpg)

![The stage (left) with the coat of arms of the Guild of St Luke on the base and the engraving (right) that was part of the chaerte at the time.[16]](/library/_shared/images/BC/virtual-exhibitions/sl4-4.jpg)