Studying social service robots: potential colleagues, instead of competitors

| Date: | 21 February 2024 |

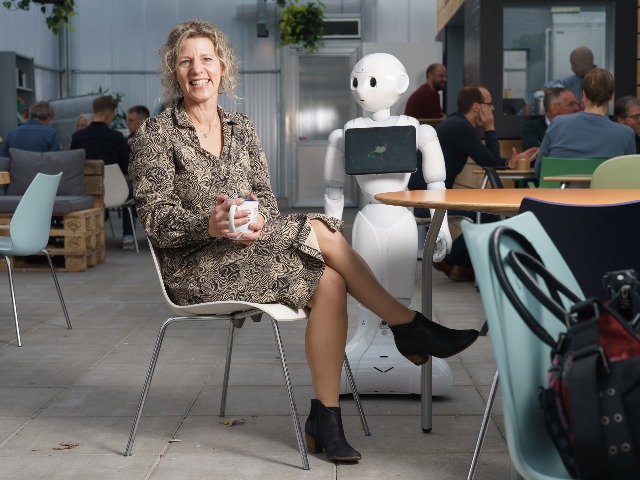

As a researcher and Professor of Service Marketing, Jenny van Doorn strives to be on the forefront of new developments and is passionate about discovering consumers’ reactions to societal transitions. One of the next frontiers of societal transitions is the use of social service robots, something she is fascinated by and has already spent some years studying. Having recently received a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO), she can continue to do so.

Jenny van Doorn’s journey into the topic of social service robots started in 2015, at a so-called Thought Leadership Conference of the Journal of Service Research. “The focus of the conference was the question what would be major changes in how services are provided in the future, and I had the privilege to discuss this question with leading scholars in my field. We quickly started highlighting various technologies as the most significant force of change. We decided to zoom in on robots that socially interact with their user. We argued that if such robots are employed as service employees, they are fundamentally different from previous waves of service automation, such as cash machines, because they also engage consumers on a social level. We coined this as robots having “Automated Social Presence”. The article that was written based on this conference marks the start of my research into the acceptance of social robots.”

Fascinating but frustrating

Over the past years, Van Doorn has acquired and used several robots, such as the Nao, the Pepper, the Meccanoid and the Temi. “I simply find them fascinating. Interacting with a robot is a social experience that can be deeply satisfying if it goes well, but also very frustrating if the robot does not understand me. I have witnessed reactions of many different types of people to encountering a robot ‘in the wild’ – at the entrance of our university, in a lecture room, in the Groningen Forum, and in an elderly care institution. People are often very curious about the robot, yet not everyone is eager to interact with it.”

This hesitance to interact with robots, was also something she encountered in her first research projects focused on the acceptance of social robots by consumers. “One of the first insights I obtained is that people disliked it when they were served by a robot instead of a human in hospitality. Colleagues from Maastricht University found the same results, in a different setting though, namely that of elderly care. This finding was actually a bit disheartening and led me to rethink my focus on robots in service – it is perhaps better to stop using robots in service altogether? What made me continue is what I got back from various societal partners.”

Van Doorn talked to elderly care organizations and health care organizations that all emphasized how difficult it was to find sufficient staff to serve their clients, and how much work pressure their staff experienced, and how often they had to ask them to work double shifts. The COVID-19 crisis made this even worse, and also highlighted advantages of robots – they cannot transmit the virus, they cannot get sick themselves. “This motivated me to look for the sweet spots and think of situations and contexts when robots are a good way to serve people.”

Continuing her research on service robots led Van Doorn to uncover some surprising details. “We discovered that making robots more human-like had a very negative effect on people’s acceptance of a robot serving them. Even small things, such as giving a robot a human name made a difference, which was something I did not expect. Next to this, we found that people actually welcome robot service when they have to acquire an embarrassing product, or are in an embarrassing situation. Yet, again the robot should not be too human-like – a human-like robot again makes people feel embarrassed.”

Not a replacement, but an addition

Van Doorn started her research journey into robots, and her first projects and papers, with the idea that robots could replace humans, but she quickly realized that that is not going to happen. “Instead of robots taking over our jobs, it will be us working side-by-side with robot colleagues. It is expected that, within the next decade, one-third of current fulltime occupations will be transformed into augmented services delivered by teams of humans and robots/AI. So, the real question is: how will we all function alongside a robot colleague? And how do consumers react to human-robot teams?” These two questions are central to her new research project titled ‘My robot colleague will be with you in a moment – Public service by teams of robots and humans’, for which Van Doorn recently received a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

It is a topic of great importance. As the population in many countries gets older, the demand for health care is rising, and the shortage of people working in health care is reaching alarming levels. As a consequence, more and more organisations turn to robot technology to address these challenges.

Due to this partial focus on health care in her research, Van Doorn is also actively involved the Centre for Public Health in Economics and Business (CPHEB), one of the Centres of Expertise that are part of the Faculty of Economics and Business. Within CPHEB, she collaborates with colleagues from various departments on interdisciplinary research with links to health care. Van Doorn: “Robots can help solve the huge health care demand and will work side-byside with human colleagues. For us as a society, it is therefore important to know how robots and humans can best work together, both from the perspective of the client who is served, and the perspective of the human colleague who has to work with robots.”

Fundamental change in how we work

The use of service robots in health care is just one of the many technological developments that influence our lives and work places, there are many technologies that remain for Van Doorn to examine in future research: “I am fascinated by the quick developments in technology these days that entail that many of us are now co-working with technology. Students study with the help of ChatGPT, amateur and hobbyist artists use DallE to create art – and professional artists are having a heated debate about (not) using such tools and what it means for the arts sector in general. There is a lot to be discovered about the social and societal implications of these developments – how does co-creating with such technology make us feel about ourselves, the outcomes of our work and our jobs/hobbies? What are the consequences in the workplace? I am not worried about ‘AI taking over all our jobs’, yet I am sure that the rise of AI will fundamentally change how we do things.”