'Polluted' white dwarfs show that stars and planets grow together

Observations and simulations of 237 white dwarfs strengthen the evidence that planets and stars rapidly form together and become planetary systems. An international team of astronomers and planetary scientists, including Tim Lichtenberg of the University of Groningen's Kapteyn Institute, published their findings on Monday in Nature Astronomy.

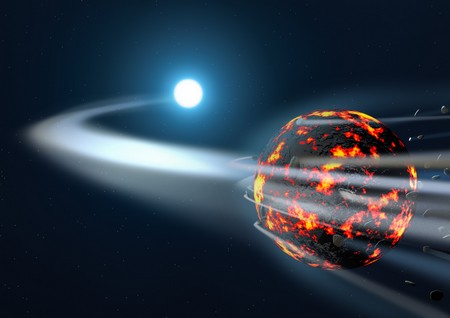

Planets form in a disk of hydrogen, helium and small particles of ice and dust around a young star. The dust particles clump together and grow slowly at first. When enough of them are packed together, so-called planetesimals can form. These can subsequently grow into planets. Any debris is left behind as asteroids or planetesimals. That debris still occasionally slams into the star, providing a kind of fossil imprint of early geological processes.

White dwarfs

There is debate among astronomers and planetary scientists about whether stars form first and planets only many millions of years later, or whether planet formation begins almost simultaneously with the star. To answer this question, the researchers analyzed light from the atmosphere of 237 so-called polluted white dwarfs. These end-of-life stars are called polluted because, in addition to helium and hydrogen, they temporarily contain heavier elements in their atmosphere, such as silicon, magnesium, iron, oxygen, calcium, carbon, chromium and nickel.

‘The enrichment with heavy elements indicates that iron-core planetesimals have been falling onto the star,’ said Tim Lichtenberg, one of the study's authors. He was working at the University of Oxford when the research began and is now at the University of Groningen. “And such an iron core can likely only form if the fragment has been previously strongly heated. This is because that's when iron, rock and more volatile elements are separated.’

Simulations

Additional simulations of asteroid collisions reinforce the observations and show that the debris falling into the stars must be quite small. "The iron cores, as with asteroids in our own solar system, were likely created by heat released during the decay of short-lived radioactive elements," Lichtenberg said. ‘We suppose that the element in question is aluminum-26. That element also drove the formation of planetary cores in our own solar system.’ Aluminum-26 has a half-life of about 700,000 years. As a consequence, the researchers argue that planet formation around what are now white dwarf stars must have occurred in the first few hundred thousand years of the stars’ lives.

In the future, the researchers plan to expand their research on white dwarf pollution. For example, the amounts of nickel and chromium in these "celestial graveyards" provide information about how large an asteroid or planetesimal was when its iron core formed. And that can give insights into atmospheric composition of Earth-like exoplanets.

Referentie: Amy Bonsor, Tim Lichtenberg, Joanna Drazkowska & Andrew M. Buchan: Rapid formation of exoplanetesimals revealed by white dwarfs , Nature Astronomy, 14 november 2022.

Text: NOVA

| Last modified: | 28 November 2024 3.34 p.m. |

More news

-

20 December 2024

Three FSE researchers receive NWO M1 grant

Dr. Antonija Grubišić-Čabo, Dr. Robbert Havekes and Prof. Jan Komdeur receive an NWO M1 grant

-

19 December 2024

NWO ENW-XL million grants for RUG research projects

Four researchers from the Faculty of Science and Engineering (UG) receive NWO grants of 3 million euros for their research projects.

-

19 December 2024

Jacquelien Scherpen honoured with Hendrik W. Bode Lecture Prize 2025

For her achievements in the scientific development of control systems and engineering, Rector Jacquelien Scherpen has received the 2025 Hendrik W. Bode Lecture award from the IEEE Control Systems Society (CSS).