That’s cool: spin transport in an insulator

There’s more to electrons than a negative charge. They also possess a property called spin. Electron spin can move through insulators, whereas electrons can’t. PhD student Jing Liu has made an exciting discovery about this process. She published an article about it on 10 April in Physical Review B Rapid Communication.

Electron spin is a magnetic property, which can take the values ‘up’ or ‘down’. Spin can be used to store, transport and manipulate information. Much work in the lab of Professor of Applied Physics Bart van Wees, last year’s winner of the Dutch Spinoza Prize, is focused on understanding the fundamental physics behind spin and spin transport, with the long-term aim to build so-called spintronics – electronic devices which operate on spin rather than charge.

This is interesting for several reasons. First, using spin adds a quality to electrons which can carry information. Furthermore, devices that operate on electron spin switch faster, use less energy and produce less heat. Especially so when spin is transported through an insulator. Insulators don’t allow electrons to move (which would generate heat), but the spins can pass through, like a 'wave’ passing through a stadium .

Surprise

Jing Liu, a PhD student in the Van Wees lab, has investigated the physics behind the transport of spins through an insulator (Y3Fe5O12, Yttrium iron garnet or YIG for short). She studied the transport of magnons, quasiparticles made up of a collective excitation of the electrons' spin structure in a crystal lattice. In simple terms: a magnon describes spin waves in a material in a particle-like fashion.

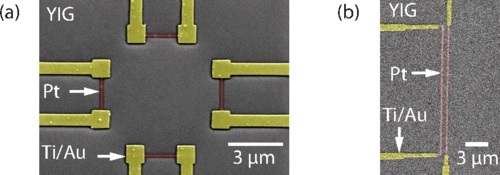

‘We created a device in which we can measure magnon currents in the YIG insulator’, Liu explains. To her surprise, the measurements revealed so-called anisotropic transport: the magnon transport was directionally dependent. Although this had never been seen for magnon spin transport, it is a familiar phenomenon in electron transport through ferromagnetic materials. It can be caused by an interaction between the spin of an electron and its motion, an effect that is called spin-orbit coupling.

New questions

‘To find this in our device was a surprise, as spin-coupling is very weak in the material we used’, says Liu. The finding will therefore trigger more research: what exactly is happening in the insulator? But apart from producing new questions, her research also provides a new tool for research: ‘We now have a method to measure anisotropic transport. But also, the fact that it occurs means we can probably manipulate spin transport in our device.’

For her next project, Liu will investigate two different types of magnons, with low and high energy. ‘The high energy magnons behave more like particles, the low energy magnons are more wave-like. I aim to study their interaction.’ The long term vision is creating spintronic devices that work without electron currents and therefore don’t produce heat. A cool prospect!

The work by Jing Liu is part of the research program Magnon Spintronics financed by FOM foundation for Fundamental Research of Matter (now part of NWO).

Reference: J. Liu, L. J. Cornelissen, J. Shan, T. Kuschel, and B. J. van Wees: Magnon planar Hall effect and anisotropic magneto resistance in a magnetic insulator. Phys. Rev. B 95, 140402(R) – Published online10 April 2017

DOI 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.140402

| Last modified: | 15 December 2017 11.02 a.m. |

More news

-

10 June 2024

Swarming around a skyscraper

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

21 May 2024

Results of 2024 University elections

The votes have been counted and the results of the University elections are in!