New molecular machines are textbook stuff

When he was studying chemistry at Nanjing University in China, Jiawen Chen read about University of Groningen Professor of Organic Chemistry Ben Feringa in his textbooks. Now, he is defending his PhD thesis in Groningen with results that might end up in those same textbooks.

‘I am standing, as they say, on the shoulders of giants.’ Chen may be modest, but his results are a big step forward in the development of light-driven molecular machines. ‘This group has over fifteen years of experience in working with these motors.’ Reading about the molecular motors that the Feringa group has produced inspired Chen to apply for a PhD there. ‘I sent an email, got the job and then had to find out where Groningen was.’

Chen didn’t find it hard to adapt to the European research culture. ‘My English was reasonably good, and my Master’s thesis had been supervised by a professor who had worked in Germany and who had introduced me to the European style.’

The results of his four-year project are impressive. One of his first accomplishments was to redesign the oily motor molecules to make them water soluble. Right from the start, Feringa had envisioned his motors working in a biological (and therefore watery) environment. Chen added some water-soluble groups to the motor to make it soapy.

In an aqueous solution, Chen created a slow-moving light-driven motor molecule that self-assembled into end-capped nanotubes, but would switch morphology into vesicles upon light irradiation, and back into tubes by applying heat. Thus, he was the first to change the shape of a larger nanostructure using motor molecules. This opens up the way for applications to store and deliver compounds in such nanostructures.

Next, Chen fixed a molecular motor to a surface and added a rigid ‘paddle’ to create a light-driven nano-stirrer. Using paddles of different length and rigidity, Chen was able to measure how kinetic and thermodynamic parameters affect the amount of solvent which the stirrer can displace. Future applications could lie in mixing ingredients on a lab-on-a-chip, or moving materials in solution, possibly even inside cells.

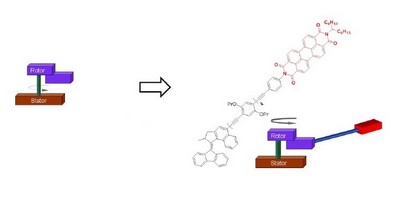

The visualization of the movement of a single molecular motor was another challenge, solved by attaching a fluorescent group to the motor using a long spacer. Single molecule techniques allowed Chen to directly view the rotary motion, another first in this field. This experiment with a small artificial molecular motor mimics to some extent a classic experiment in which the rotary movement of the much larger cellular ATPase protein complex (which produces the universal energy carrier ATP) was visualized.

It may all sound like a walk in the park, but the synthesis of one light-driven motor that could be fixed to a surface took 34 steps. And he first had to find out which steps worked. ‘Sometimes, I had to change my approach and redirect the synthetic path I had chosen.’ Not every step ran smoothly either. He estimates it took him about a year to get the job done. ‘But’, he smiles ‘it was very good training for my synthetic skills!’

Ben Feringa believes that Chen’s work represents a watershed in molecular machine engineering. ‘We can build a motor from scratch, visualize its movement, mimic natural motor systems and place the motors on a surface. This opens up the way for all sorts of smart materials and surfaces.’ Chen’s work has featured in the news in the US and further afield.

So who knows, perhaps the work of Jiawen Chen will end up in the textbooks and will inspire the next generation of chemistry students! He will now continue working in Groningen as a postdoc. Apart from the science, there are personal reasons for this choice: he just became a father, so this is not the best time to relocate. It was the inspiration behind one stelling in the list of propositions accompanying his a thesis: ‘My son is the best synthesis so far in my life. And now I have begun to raise my son myself, I am starting to realize more and more how great my parents are.’

Jiawen Chen will defend his PhD thesis ‘Advanced Molecular Devices Based on Light-driven Molecular Motors’ on 30 January at 11 a.m. in the Martinikerk.

This research project was done at the Stratingh Institute for Chemistry, University of Groningen. Read more about the bachelor and master programs in Chemistry.

See also the University of Groningen press release

| Last modified: | 19 September 2017 12.51 p.m. |

More news

-

10 June 2024

Swarming around a skyscraper

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

21 May 2024

Results of 2024 University elections

The votes have been counted and the results of the University elections are in!