The history of Kapteyn

The time of Kapteyn

The Institute is named after its founder, Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn, who lived from 1851 to 1922. Kapteyn was appointed professor of astronomy and theoretical mechanics in 1878 at a time when there was no astronomical tradition, let alone an observatory, in Groningen. The chair was established as a result of the new Higher Education Act of 1876, which stipulated that the three government-subsidized universities of Groningen, Leiden and Utrecht would teach the same curricula, so a new chair of astronomy had to be established in Groningen. Leiden and Utrecht already had such chairs and these were supported by observatories. However, the government did not make money available to establish another one in Groningen (and the other two astronomy professors together effectively stopped this by giving negative advice so they did not have to share the available money with a third party).

Photographic plates

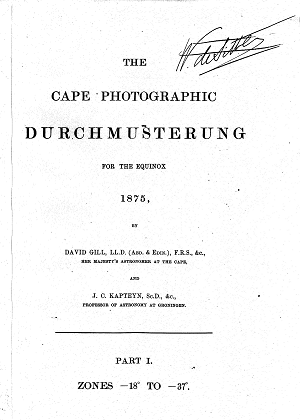

In Cape Town, Sir David Gill was struck by the possibility of counting and cataloguing stars on photographic plates and mentioned this in correspondence with Kapteyn. He did not have the manpower to measure star positions and magnitudes (astronomical jargon for brightnesses), but continued photographing the southern sky anyway. Eventually, he managed to persuade Kapteyn to offer his services. Kapteyn continued measuring Gill's plates and this resulted, after 12 years of hard work, in the publication of the Cape Photographic Durchmusterung in three volumes between 1896 and 1900. This Durchmusterung catalogued the positions and magnitudes of 454,875 stars. To carry out these tasks, Kapteyn established an Astronomical Laboratory, an ‘Observatory without telescopes’, which was eventually named after him.

'Star streams'

Kapteyn was particularly interested in the structure of the ‘sidereal system’. But this required measuring distances from stars. However, direct measurements of the reflection in the sky of the Earth's motion around the sun are only possible for the nearest stars. He designed a new, statistical method, called secular parallax measurements, to statistically estimate the distances of stars, using the fact that the displacement of a star in the sky due to the Sun's movement through space decreases with distance.

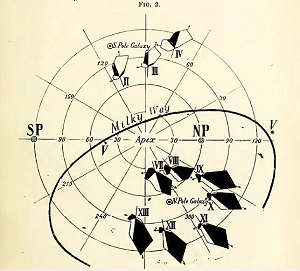

These displacements in the sky, called proper motion, naturally include a component due to the star's own motion in space and can therefore only be applied statistically. This requires that the proper motion of stars in space is random and isotropic (without preferred directions). Kapteyn's first major discovery was that this is not in fact true, but that there are apparently two ‘star streams’, which he announced at the St. Louis International Exposition in 1904. He discovered that the space motions of ‘ordinary’ stars near the sun showed two preferred directions; this was later explained by Karl Schwarzschild as the result of an anisotropy of stellar motions in a velocity ellipsoid with unequal axes. The streams are then the opposite directions in which the random motions are greatest.

Space distribution of stars

Kapteyn developed methods to derive the space distribution of stars from star counts as a function of magnitude (brightness) along the entire sky and mapping the apparent displacements, called proper motions, of stars due to their movement in space relative to the sun.

Absorption of starlight

He was very concerned about the absorption of starlight by interstellar material and published two articles on the subject in the Astrophysical Journal in 1909. Eventually, he concluded that there was indeed evidence for such absorption. He had correctly realized that absorption (in practice, mainly scattering of light by small dust particles) would depend on wavelength, making stars appear redder at long distances. In fact, his inferred quantity, improved in his student Pieter van Rhijn's thesis, is not too bad, although it is now known to be limited to close to the plane of the Milky Way galaxy.

Later, Harlow Shapley in the US showed that absorption towards a globular cluster outside the Milky Way was almost absent, at least significantly less than Kapteyn's value. This led astronomers, including Kapteyn, to mistakenly follow Shapley and ignore interstellar absorption everywhere, including near the Milky Way, in the ‘disk’ of the Galaxy.

International collaboration

Kapteyn also pioneered and was very successful in international cooperation; the need for him to work with plates taken by others and measured in his observatory without a telescope, and his Anglo-Saxon orientation (as opposed to the German orientation so common at the time) must have been important factors in this.

George Ellery Hale

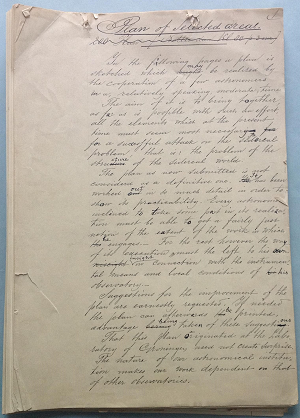

He became a close friend of George Ellery Hale and spent his summer months between 1908 and 1914 as a research associate at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California. In 1906, he published his Plan of Selected Areas, in which observatories around the world would measure positions, magnitudes, proper motions (and, for the brightest, spectral types and radial velocities) in a series of carefully chosen fields scattered across the sky.

George Ellery Hale was so impressed by Kapteyn that when he was in the process of building the world's largest telescope, the 60-inch on Mount Wilson near Pasadena and Los Angeles in 1906, he adopted Kapteyn's plan as the main observing programme for his new giant telescope. This also resulted in Kapteyn being invited to become a research associate of the Carnegie Institution of Washington at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California to oversee this work. After his first visit, Kapteyn, accompanied by his wife, spent his summer months in California from 1908 until 1914, when the ‘Great War’ made travel across the Atlantic impossible.

‘Astronomical Laboratory’

Kapteyn never succeeded in establishing an observatory in Groningen. He did, however, secure a building for his ‘Astronomical Laboratory’, which was opened at a temporary location in 1896 and, after several moves, got its final location in 1913 (in the Broerstraat in the centre of Groningen next to the university's central building). After Kapteyn's retirement in 1921 and shortly before his death in 1922, the trustees of the University of Groningen decided to name the astronomical laboratory after him.

Towards the end of his life, Kapteyn, together with Pieter van Rhijn, published a schematic model for the distribution of stars in space (Astrophysical Journal, 1920), followed by his ‘First attempt at a theory of the arrangement and motion of the Sidereal System’ (Astrophysical Journal, 1922). In it, he laid the foundations for dynamical studies by combining observed space distributions with motions and derived a first value for the density of matter near the sun.

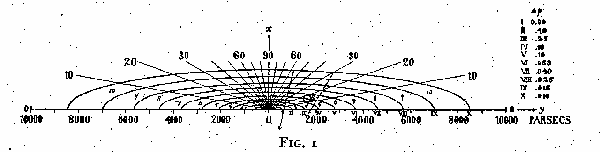

Kapteyn Universe

This Kapteyn Universe, a highly flattened system with the Sun reasonably close to the centre suffered in the plane direction under absorption but in the vertical direction is even now very close to what we now think it is. By neglecting absorption, the Kapteyn Universe is about three times too small in the longitudinal direction compared to what we now call the ‘disk’ of the galaxy. Shapley had found that globular clusters were distributed in a roughly spherical structure, concentrated towards a centre in the plane of the Milky Way, but this was much larger than Kapteyn's Universe. This is now the Milky Way's ‘halo’, but partly due to absorption, Shapley's galaxy is a factor of two too large.

Interstellar absorption

Kapteyn is now less prominent internationally, to some extent because his work on the structure of the Milky Way is usually seen in the US as a competition between him and Shapley, that was won by the latter.

Kapteyn is described as making a capital blunder by ignoring interstellar absorption, when in fact this was prompted by Shapley. Another important reason is that after the war, Kapteyn took the position that it was a big mistake to exclude Germany and other defeated nations from international organizations such as the League of Nations, the International Research Council and the International Astronomical Union, a position for which he was heavily criticized and condemned by many scientists and astronomers in the UK and the US in particular.

Van Rhijn and Blaauw

In 1921, Kapteyn was succeeded as professor of astronomy and director of the astronomical laboratory by his assistant Pieter J. van Rhijn (1886-1960). The latter had received his doctorate from Kapteyn in 1915. Kapteyn's first student, Willem de Sitter (1872-1932; PhD in 1901) had become director of the Leiden Observatory.

Jan Hendrik Oort

Kapteyn's most famous student was Jan Hendrik Oort (1900-1992), who had come to Groningen to study because of Kapteyn. He wavered between physics and astronomy and repeatedly stated that he was converted to astronomy by Kapteyn. He worked under Kapteyn on high velocity stars, which would later put him on the discovery trail of galactic rotation, but had yet to begin thesis research in 1922. De Sitter offered him a job in Leiden and, after working at Yale for two years under Frank Schlessinger, he moved to Leiden. He eventually obtained his PhD in Groningen under van Rhijn in 1926 on the subject he had already been working on in his Groningen years. Other students of van Rhijn, such as Peter van de Kamp (1901-1994; PhD in 1926) and Barthelomeus (Bart) Jan Bok (1906-1983; PhD in 1932) moved to the US, where a job in astronomy was easier to get than in the Netherlands. Adriaan Blaauw (1916-2010) had come from Leiden to work with van Rhijn and worked in Groningen during World War II. He eventually obtained his PhD in 1946, but went back to Leiden (Blaauw eventually returned).

Telescope for the Laboratory

Van Rhijn's attempts to get a telescope for the Laboratory with government money failed. In 1931, he did manage to get a 55 cm reflector and dome on the laboratory building, financed with private money. This telescope was mainly used by van Rhijn and Jan Borgman for studies of interstellar redness. In 1959, the telescope was removed because of structural problems with the building.

The work under Van Rhijn during his long tenure as professor and director (1921 to 1957) concerned the continued implementation of the Plan of Selected Areas. It was not very innovative, but time-consuming and routine work, and the Kapteyn Laboratory lost much of its prominence. Most of the work went into determining the spectra of stars in these areas; in collaboration with the Bergedorfer Sternwarte near Hamburg, prismatic objective plates were analyzed in all areas of the northern hemisphere, resulting in the 'Bergedorfer Spektral-Durchmusterung der 115 nordlichen Kapteynschen Eichfelder', completed in 1953. Blaauw later often complained that Groningen should have been in the title because a significant part of the work was carried out there. Undeniably, the Kapteyn Laboratory deteriorated badly during the van Rhijn years.

Adriaan Blaauw

In 1957, after van Rhijn's retirement, Adriaan Blaauw was appointed professor and director. Under his leadership, research broadened into several other areas. Blaauw was also very much involved in the founding of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), an initiative of Oort in Leiden and Walter Baade, a German who worked most of his life at Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. After the first International Astronomical Union symposium on Galactic Research, held near Groningen in 1953, staff member Lukas Plaut was assigned to carry out the Palomar-Groningen Survey of RR Lyrea stars in one of ‘Baade's Windows’ towards the Galactic Centre, which lasted until the early 1970s. Jan Borgman facilitated that by designing and building an instrument that could electronically compare star fields so that variable stars could be easily recognised (an automated version of a so-called Blink Comparator used visually). Stuart R. Pottasch was appointed professor of astrophysics in 1963.

Jan Borgman

Under Jan Borgman, the Kapteyn Observatory in Roden was opened in 1965 with a 61-cm reflector. Borgman also started a ‘photometry’ working group for space research, which initially used balloons but eventually culminated in strong involvement in the Astronomical Dutch Satellite (ANS; an ultraviolet and X-ray space observatory), which was used in orbit between 1974 and 1976. The Kapteyn Observatory remained heavily involved in the early development of the ESO, eventually based in Chile after much testing in South Africa. Galactic structure remained a central area of interest. Under Hugo van Woerden, a group was formed to use the 25-metre radio telescope at Dwingeloo for studies of neutral hydrogen gas in the Milky Way galaxy, an initiative that originated from and was strongly supported by Blaauw.

After 1970

In 1968, Blaauw became part-time scientific director of ESO and, in 1970, director-general. Also in 1970, the Kapteyn Laboratory moved to a new location on the developing campus grounds near Groningen's northern suburb of Paddepoel. It is now called the Zernike Campus. The space research working group, now called Laboratory for Space Research, also moved from Roden to Paddepoel. The original Kapteyn Laboratory was used for some time as part of the university's central administrative office, but was damaged by a fire in the 1980s. The university administration seized the opportunity to demolish the building. Around the same time, a restructuring of the organisational structure of universities took place, fuelled by student uprisings demanding more involvement and influence on decisions in democratic procedures, with astronomy becoming a sub-faculty. Stuart R. Pottasch became the first dean of the Astronomy sub-faculty (later chairman of the Department of Astronomy) from 1970 to 1982.

Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope

In 1970, the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope was commissioned, and the Kapteyn Institute's radio group soon became one of its main users. Especially after observations with the 21-cm line of neutral hydrogen became possible (largely the result of the efforts of Ronald J. Allen, who had been hired as a postdoc and subsequently became a staff member), extensive studies were made of nearby galaxies, with the emphasis shifting from structure of our own Milky Way galaxy to that of external galaxies.

Star formation, interstellar medium and gas in the Galaxy remained a second major focus. In particular, the so-called flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies and the evidence that they contain large amounts of unknown ‘dark matter’ became a major topic of study. Renzo Sancisi and Miller Goss, alongside Ron Allen, Tjeerd van Albada, and Ron Ekers, led the Westerbork studies, while Pieter C. van der Kruit combined radio studies with the new field of optical surface photometry based on electronic scanning and digitizing of photographic plates with the Astrocan machine at the Leiden Observatory.

Space Research group

The Space Research group, now led by Reinder J. van Duinen, made a major contribution to the Astronomical Netherlands Satellite ANS, followed by major participation in the NL/UK/NASA Infra-Red Astronomical Satellite IRAS, launched in 1983.

Borgman had become dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences in 1975, then became Rector Magnificus and then chairman of the Executive Board of the University of Groningen, and moved to The Hague in 1988 to become chairman of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). The Space Research Laboratory became part of the Netherlands Space Research Foundation (SRON), funded by NWO.

Interuniversity Working Group on Astronomical Instrumentation

In 1981, with the beginning of Dutch involvement in the UK/NL Isaac Newton Group of optical telescopes on La Palma (Canary Islands), the Interuniversity Working Group on Astronomical Instrumentation was established in Roden with staff from the universities of Groningen and Leiden. Led by Harvey R. Butcher and Jan Willem Pel, this working group developed instrumentation for both ESO and La Palma. The group was transferred to the Radio Observatory in Dwingeloo in 1995 and made a name for itself designing and building optical instrumentation; the Kapteyn Observatory in Roden closed. In 1983, the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute moved to its current location in what was first called the Zernike building, now the Kapteynborg.

Recognition astronomy department

In 1982, Pottasch was succeeded by Ronald J. Allen as chair of the Department of Astronomy and this position was subsequently held by Hugo van Woerden from 1985 to 1991 and by Pieter C. van der Kruit from 1991 to 1994. In 1994, van der Kruit became dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences until the end of 1997. Also in 1994, the Department of Astronomy (which included the Kapteyn Laboratory in Groningen, the Kapteyn Observatory in Roden and related research within the Space Research Department) was formally recognized by the University of Groningen as a research institute, giving it a certain protected status, and was renamed the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute. Tjeerd S. van Albada became scientific director, succeeded by Piet van der Kruit in 1998.

NOVA

In 1992, the astronomical institutes at Dutch universities together formed the Netherlands Astronomy Research School (NOVA) and were recognized as such by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences. In 1998, the Minister of Education, Culture and Science organized a ‘Deep Strategy’, in which the more than 100 research schools in the Netherlands could compete for recognition as top research schools and receive significant additional funding for a period of 10 years. NOVA came out as number one in this national competition, in which only six schools were awarded top research school status. This has been extended for about a decade, with ASTRON being awarded the designation ‘exemplary’, a distinction shared with only one other research school in the Netherlands.

Expansion and renewal of the scientific staff

As a result of additional resources and the protected status of NOVA, as well as the move of the optical workshops to Dwingeloo, retirements and departure of staff to other large institutions abroad, a significant expansion and renewal of the scientific staff in Groningen took place between roughly 1990 and 2010. In 2021, there were approximately 18 permanent scientific staff and supporting technical, computer and administrative staff, about 20-30 postdocs, and more than 50 PhD students.

Scientific directors Kapteyn Institute

The scientific directors were Thijs (J.M.) van der Hulst (2005-2011), Reynier F. Peletier (2011-2017), Scott C. Trager (2017-2020), and Léon Koopmans (2020-present).

In 2017, the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences changed its name to the Faculty of Natural Sciences. Kapteyn Astronomy Institute staff have been or are closely involved in many ground and space facilities, such as ESO, La Palma, ISO, Herschel, LOFAR, SKA, Euclid, and many others. They have been very successful in obtaining external funding, in addition to NOVA, and prizes and awards. These include grants from NWO and personal grants such as the Veni, Vidi, en Vici NWO grants, and starting, consolidating, and advanced grants from the European Research Council (ERC).

Piet van der Kruit has been appointed one of the few named professors in the faculty (Jacobus C. Kapteyn Professor). Prof Amina Helmi received the highly prestigious Spinoza Prize, the highest scientific award in the Netherlands.

Literature

- Kapteyn, zijn Leven en Werken, 1928, biography of Kapteyn by his daughter Henrietta Herzsprung-Kapteyn. Translated into English by P.C. van der Kruit at https://www.astro.rug.nl/JCKapteyn/.

- In het voetspoor van Kapteyn: Schetsen uit het werkprogramma van de Nederlandse Sterrenkundigen aangeboden door vrienden en collega's aan Prof. dr. P.J. van Rhijn ter gelegenheid van zijn zeventigste verjaardag, 1956, Nederlandse Astronomen Club.

- Sterrenkijken Bekeken; Sterrenkunde aan de Groningse Universiteit vanaf 1614, 1983, publication of the Groningen University Museum (eds. A. Blaauw, J.A. de Boer, E. Dekker and J. Schuller tot Peursum-Meijer).

- The Legacy of J.C. Kapteyn; Studies on Kapteyn and the Development of Modern Astronomy, 2000, proceedings of a symposium on Kapteyn (eds. P.C. van der Kruit and K. van Berkel), published by Kluwer Academic Publishers (ISBN 978-3-319-10875-9).

- Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn: Born investigator of the Heavens, 2014, by Pieter C. van der Kruit, volume 416 in the Astrophysics and Space Science Library of Springer Publishers (ISBN 978-3-319-10875-9).

- De Inrichting van de Hemel: Een biografie van astronoom Jacobus C. Kapteyn, 2016, by Pieter C. van der Kruit, Amsterdam University Press (ISBN 978-9-462-98042-6).

- Pioneer of Galactic Astronomy: A Biography of Jacobus C. Kapteyn, 2020, by Pieter C. van der Kruit, Springer Biographies, Springer Publishers (ISBN 978-3-030-55422-4).

| Last modified: | 17 October 2024 11.27 a.m. |