Adventures in Eden

| Date: | 27 May 2024 |

| Author: | Sven Gins |

Biodiversity loss, artificial intelligence, and legal personhood of animals would seem to be topics of debate reserved for modern times. In my work as a medievalist, I cast light on the premodern roots of these interrelated topics. I read medieval encyclopaedias to study how people gave meaning to their relationships with other animals. For instance, wild boars were described as impressive but dangerous predators that, when killed, yielded delicious meat and great prestige. I also explore how medieval craftsmen translated such animal lore into allegedly lifelike ‘robots’ such as mechanised boar heads that symbolised mastery over nature. Sometimes, however, even a simple village pig could upend such ideas of control by, for instance, maiming and eating a human child. I investigate how communities responded to such preposterous events by organising court trials that turned the animals into judicial spectacles.

Each of these topics, especially the medieval robots and so-called ‘animal trials’ now have a kind of quasi-legendary status. The best way to gain a better understanding of them – or even simply to accept that they indeed really existed – is by returning to the sources. To that end, I recently travelled to northern France, to look into centuries-old manuscripts and parchment rolls and seek out other material remains of this marvellous past.

A medieval theme park

Medieval France once housed an unforgettable amusement park, described by chroniclers as ‘one of the most sumptuous works on earth’. The castle and garden park of Hesdin brought together natural and artificial mirabilia in a spectacular vision of paradise lost and reimagined. A magnificent castle overlooked steep hills, vast woods and marshlands, meticulously maintained fishing ponds and rivers – every blade of grass painstakingly engineered to evoke awe. Besides hunting grounds, the park offered a feast for the senses. Guests wandered the resplendent gardens, inhaling the aromas of various herbs and thousands of fruit trees. Musical delights awaited visitors of the aviary, where real and artificial songbirds perched on a golden tree. Nature’s wonders could also be seen in action in the park’s héronnière, home to the counts’ herons, and in the menagerie, which housed a bear, a wild boar, and exotic wildlife, including a camel.

Hesdin’s fame mostly lies in its technological ingenuity, which was particularly evident in the marshland pavilion. Here, unsuspecting visitors faced violent talking statues, distorting mirrors, rooms with artificial weather systems that could conjure rain, lightning, and snow, and even a prank gallery with water conduits all over to ensure that ‘nobody ... could possibly prevent themselves from getting soaked’. Since emperor Charles V razed the city, castle, and park of Hesdin in 1553, sadly all that seemingly remains now is its story.

Paradise in parchment

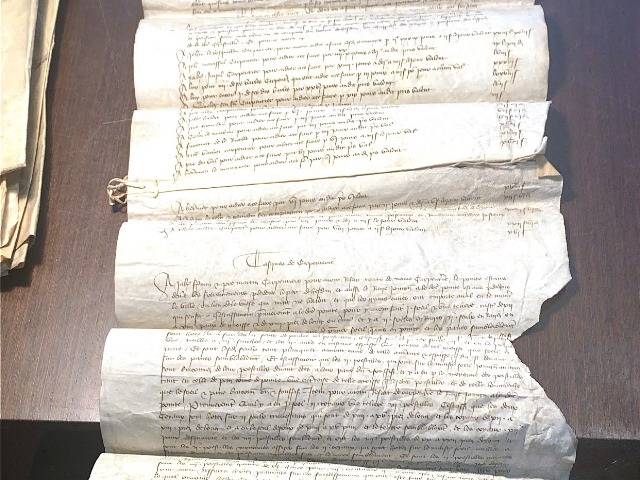

To learn more about this wonderful place, I recently spent a week in Lille’s departmental archives combing through ducal records. My goal: acquire new knowledge about the animals and robots (engiens in Middle French) that populated Hesdin under the dukes of Burgundy (1384-1477). I came across many bills detailing expenses for works in and around the castle of Hesdin. Various documents reference wages paid to various people employed as ‘painter and master of engines’ (paintre et maistre des engiens). In 1439, one Colart le Voleur apparently addressed a personal letter to Duke Philip the Good, asking for remuneration of the wood, rope, and ‘powder’ he had purchased to restore a broken window. This same Colart had previously restored the prank gallery in 1433 – including several windows that could close themselves and wet guests, and devices that covered nobles in soot. The letter’s window was probably part of that very gallery, likely one that assailed guests with a kind of powder whenever they tried to open it.

While in Lille, I also chanced upon a certificate attesting to the execution of a pig that had killed a child in Bailleul, 1486. As scholarly literature on animal trials mentions no cases from northern France, I did not expect to encounter such records here. Imagine my delight at this discovery: firsthand evidence that there are still animal trial records waiting to be (re)discovered in the archives!

My itinerary then led me to spend the next week at the Centre Mahaut d’Artois, near Arras. The parchment rolls stored here provide an extensive overview of how Hesdin’s castle and garden park initially developed under count Robert II and his heir, countess Mahaut of Artois. The records describe the (re)construction of Hesdin’s earliest automata: gesturing apes, gilded songbirds, a moving boar head... even a hydraulic elephant. These accounts also reveal the locals’ strained relationship with Hesdin’s wildlife: the counts spared no expense on rabbit, wolf, and otter hunters. One record from 1311 even indicates that they made repairs to ‘old engines to capture the otters ... and to perfect [these] engines’. Sadly, it does not elaborate on how these engines operated.

In search of lost time

Finally, I travelled to the city itself, braving the steep hills of the Hesdinois landscape to make my way to Vieil-Hesdin (about five kilometres from modern Hesdin), where I toured the vestiges of the old city. My guides painted a vivid picture of the original Hesdin: over ten thousand citizens, several churches, a great fishing pond, and a splendid castle on the hill. The local museum features over a thousand years of Vieil-Hesdin’s history – a powerful reminder that time did not stop here after the city fell. Its legacy continued, woven into new stories through the people who stayed and rebuilt, time and again.

On my final day, I did not rest but, armed with several maps and my trusty bicycle steed, set out into the idyllic northern reaches of the old park. Fancying myself something of an adventurer, I hoped to find some kind of ruins or other distinctive traces – preferably of the old marsh pavilion. My quest led me over the Chemin de St. Silvan, a reportedly old road that offers an overview of the Ternoise river valley. Yet Hesdin guards its secrets well: many of the castle and park’s areas of interest are now private property. Moreover, timber buildings like the pavilion never stood a chance against the wreck of time. Yet my search was not fruitless: eventually, I reached a set of natural springs, the so-called ‘bottomless holes’ which possibly furnished the park’s fountains with water. Following the Rue de la Font aux Dames (a reference to the gallery that used to soak aristocratic ladies), I reached Le Parcq, a village located smack in the middle of the historic park site. Its inhabitants have planted an all new ‘Garden of Eden’ where weary travellers can rest their legs before returning home, as I did.

In the weeks to come, I turn my attention to the many scanned rolls of parchment that require transcription. It has, however, come to my attention that there are several museums that reportedly possess archaeological remains of Vieil-Hesdin. It seems that another visit is in order soon...

Acknowledgements

My archival research and fieldwork was made possible thanks to financial support of the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and the Association Villard de Honnecourt for the Interdisciplinary Study of Medieval Technology, Science, and Art (AVISTA).

I thank Sébastien Landrieux and the other members of the Association des Amis du site historique du Vieil-Hesdin for their warm welcome and wonderful narration of the fortunes and vicissitudes of Vieil-Hesdin. I am also grateful to Dr Stephen Wass, who kindly shared his insights with me regarding his archaeological fieldwork in Vieil-Hesdin.

About the author

PhD Researcher - Faculty of Religion, Culture and Society, University of Groningen

Research Project: “Homo Imperfectus: Animals, Machines and the Quest for Humanity in Late Mediaeval France.” Funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) via the PhDs in the Humanities talent programme (PGW.21.029)