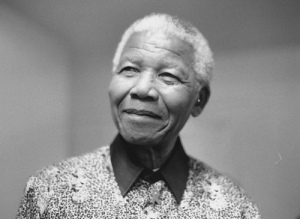

A secular saint? The Life and Legacy of Nelson Mandela

| Date: | 09 December 2013 |

| Author: | Religion Factor |

The inevitable moment of Nelson “Madiba” Mandela’s departure from this world came last Thursday evening, 5 December. Given that he had been so frail for some time, his death was not unexpected, yet that does not lessen the impact of his loss. As South Africa and the world honour his life through various services and memorials all this week, Erin Wilson discusses what Mandela’s fight for equality and justice for the marginalized and oppressed in apartheid South Africa means for an interdependent and interconnected world and whether Mandela is what some have called “a secular saint.”

The death of Nelson Mandela is being mourned throughout the world on a scale rarely witnessed. His struggle for his own freedom and the freedom of South Africa from the brutal system of apartheid is one that has inspired subsequent generations of political leaders and human rights activists the world over. He has been revered, honoured and admired by billions. Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, another key figure in the reconciliation process Mandela implemented to rebuild post-apartheid South Africa, described him as “the leader of our generation who stood head and shoulders above his contemporaries — a colossus of unimpeachable moral character and integrity, the world’s most admired and revered public figure… he will go down in history as South Africa’s George Washington, a person who within a single five-year presidency became the principal icon of both liberation and reconciliation, loved by those of all political persuasions as the founder of modern, democratic South Africa.” (1)

Despite their close friendship and the work they did in pursuing justice and reconciliation in post-apartheid South Africa, Mandela is regarded in an entirely different way from Tutu. Tutu has always been overtly religious in his activism and his interventions in public life. Mandela, despite his own strong, if eclectic, spirituality, has rarely made overt religious reference a large part of his public rhetoric and his activism (2). He has instead emphasized values of justice, equality, the human spirit and common humanity, without reference to any particular religious or political worldview. This may be why one BBC reporterdescribed him as the closest the world has to a secular saint.

Yet it seems to me that he was neither strictly secular nor strictly religious and describing him as either secular or religious in some ways only feeds the divisions that Mandela strove to transcend throughout his life. Mandela sought to identify, utilize and build upon the values that were shared across traditional social, political, economic, racial, cultural and religious divides in his efforts to pursue justice and freedom. Instead of trying to promote the success of a particular political view, people, religion or himself, Mandela sought to maximize the opportunities for human dignity and flourishing for as many people as possible. He was on occasion criticized by members within the ANC for being too willing to compromise and accommodate those who had been involved in the oppression of black South Africans in the past. Yet Mandela was more concerned with restorative justice that would both acknowledge the wrongs of the past and enable the building of a shared vision for the future, rather than retributive justice that would only accuse and punish prior wrongdoings.

In his bestselling autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela described his time in prison, stating “A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones”. At a time when the world is facing dire challenges that require both the addressing of past wrongs and the building of a shared vision for a common global future, it seems apt to consider this sentiment in a broader context of a globalized and interconnected world, where neoliberal economics have generated mass inequality and widened gaps between rich and poor, and where those who are stateless are often unable to access their rights and are treated as criminals for seeking safety, protection and the opportunity for a life of dignity.

How will our generation, particularly those of us who live comfortable, safe, privileged existences in developed countries, be remembered for the way we treated the most marginalized and disenfranchised members of our global community? Is there not just a hint of hypocrisy as political leaders around the world fall over themselves to pay tribute to Mandela’s memory yet at the same time ignore the plight of the world’s poor, punish, criminalize and imprison refugees for seeking asylum and fail to take seriously the implications of climate change for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, not to mention failing to adequately address poverty, homelessness and unresolved legacies of colonial injustice in their own national communities? Mandela’s death and the inspiration that his life continues to be should encourage all of us who admire him and what he stood for to soberly reflect on our own lives and what more we could be doing to follow his example, not simply utter platitudes about a life well-lived.

As we honour his memory and his legacy, we should also remember his flaws. Mandela was not perfect. He was a fallible human being, like all of us. He failed to grasp the scale of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa, something that he later tried to amend (3). He deeply offended leaders of Australia’s Indigenous community who had supported him throughout his struggle for freedom in South Africa when he visited Australia in 1990, failing to raise their cause with the government of the day, a cause that shared many similarities with the plight of black South Africans (4). He also possessed an at times fiery temper that threatened to derail South Africans transition negotiations. (5) He said of himself “I’m not a saint unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.” Yet this in some ways makes him all the more remarkable and inspirational. If someone as influential and widely respected as Mandela can not only make mistakes, but admit them, apologise for them and pull himself back up after them and continue to strive for justice, equality and dignity for humanity, then surely that is something that all of us can at least try. May we all strive to be this kind of saint, secular, religious or otherwise.

Erin Wilson is the Director of the Centre for Religion, Conflict and the Public Domain, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Groningen. This article was originally published at ABC Religion and Ethics

(1) http://allafrica.com/stories/201312051793.html?viewall=1

(2) D. Lieberfeld, 2003. “Nelson Mandela: Partisan and Peacemaker” Negotiation Journal 19(3), p244

(3) http://allafrica.com/stories/201312051793.html?viewall=1

(4) http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2013/07/05/when-nelson-mandela-came-australia

(5) http://allafrica.com/stories/201312051793.html?viewall=1