Godwit migration is learned rather than innate

The timing, route, and destination for godwit migration is learned rather than innate. Researchers at the University of Groningen discovered this in a daring experiment, which is being published in the latest issue of the journal Current Biology.

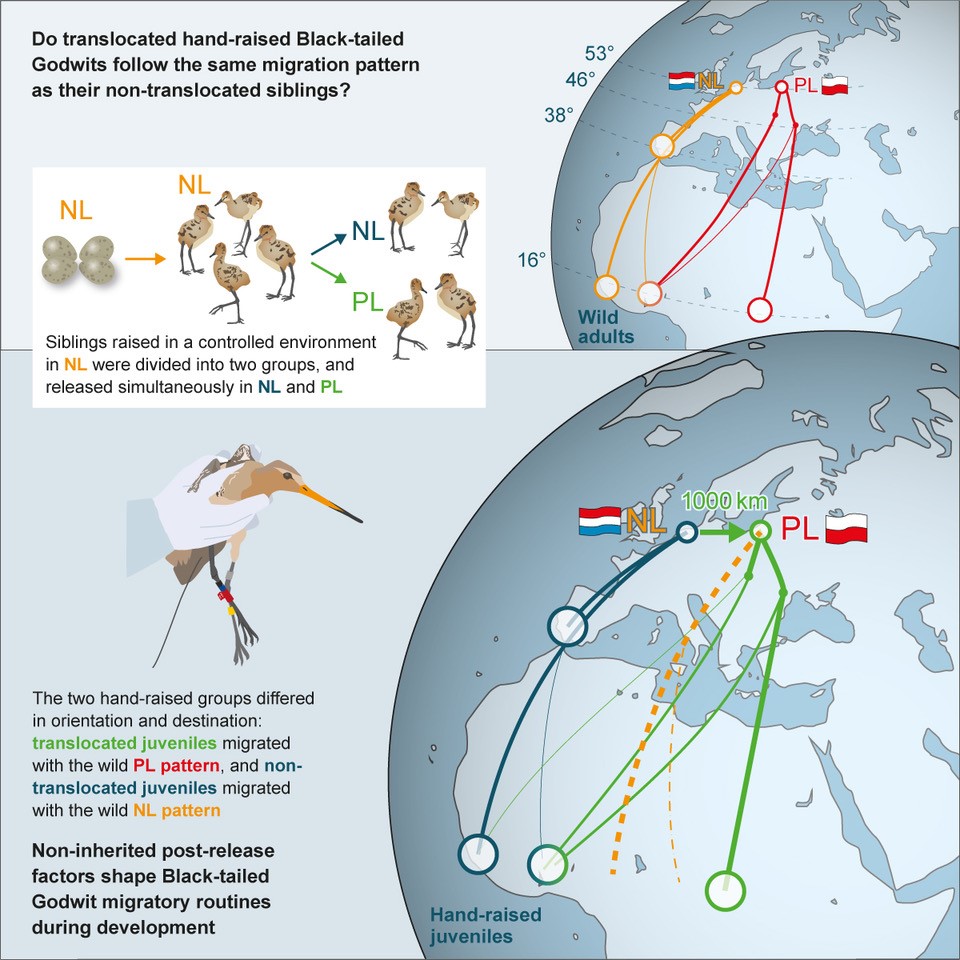

The researchers raised a number of birds themselves. These godwits were brought to Poland shortly before migration time. They subsequently followed the entire migratory routes of Polish godwits. Their nestmates who started their migration from the Frisian breeding area flew along the 'normal’ migratory route. ‘This is a clear indication that migratory behaviour in these birds is certainly not only genetic or otherwise innate,’ says project leader, final author, and Spinoza prizewinner Theunis Piersma. ‘The godwits apparently learn their migration route and destination from other birds or other factors from their environment.’

Growing up monitored

For their experiment, the researchers gathered full nests of four godwit eggs each from intensive agricultural areas. They knew from previous years that the natural chance for survival of these nests was minimal. After hatching the eggs with an incubator, the birds were raised ‘manually'. Piersma: ‘During the day we would let them hunt insects while being monitored by interns. At night they would sit inside and receive some extra insect food from us.’ By the time the chicks were fledging, the group was split up by the researchers. Half of the birds from each nest were moved one thousand kilometres to the east—to the breeding area for Polish godwits. The other half remained in Friesland. The researchers released some of the birds immediately at the natural moment of fledging, while keeping the others in captivity for another month.

Transmitters

Small transmitters weighing six grams were placed on the birds at the moment of release. These transmitters showed that the birds who moved to Poland followed the migration routes and destination of their Polish counterparts, while the Dutch chicks followed the normal, more western route toward slightly more western wintering grounds in Africa. Eventually, most Polish godwits spent the winter several thousands of kilometres further to the east in Africa. They also made an extra stop in Europe, like Polish godwits normally do.

Going to school

Piersma is exhilarated by the results. ‘The experiment clearly shows that genetics are not the decisive factor. These godwits mainly learn from their environment. They go to school, as it were. A next step in the research could be to study who exactly they learn from. Is it from older birds of the same species? Or perhaps from altogether different species? Do the birds maybe even 'talk’ to each other?

Flexibility

Besides answers to biological questions, the study contains an optimistic lesson, according to Piersma. ‘It shows that birds are more flexible than we assumed. They learn from their environment. This means that, provided that there are plenty of habitats along the migration route, migratory birds can more easily adapt to changes in suitable habitats than we initially thought.’

Questions from answers

By publishing the unambiguous results of his translocation experiment, Piersma is rounding off his Spinoza 2014 project. ‘With this controversial experiment, we hoped to take migratory birds out of ‘genetic framing’ and instead assign a much larger role to other birds of the same species and other aspects of the environment than they were initially thought to play. This instantly leads to new questions, because what is the nature of the information exchange which they apparently make use of?’

Meer informatie

- Abstract of underlying PhD-research

- Theunis Piersma

| Last modified: | 30 May 2023 1.37 p.m. |

More news

-

25 April 2025

Leading microbiologist Arnold Driessen honoured

On 25 April 2025, Arnold Driessen (Horst, the Netherlands, 1958) received a Royal Decoration. Driessen is Professor of Molecular Microbiology and chair of the Molecular Microbiology research department of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the...

-

24 April 2025

Highlighted papers April 2025

The antimalarial drug mefloquine could help treat genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, as well as some cancers.

-

22 April 2025

Microplastics and their effects on the human body

Professor of Respiratory Immunology Barbro Melgert has discovered how microplastics affect the lungs and can explain how to reduce our exposure.