Thighbone in church not from James the Apostle

As far back as the sixth century, relics attributed to the apostles Philip and James have been held in the Santi Apostoli church in Rome. The relics comprise a thighbone (femur), shinbone (tibia) and foot. However, research suggests that the thighbone, originally thought to be that of James the Apostle, does not belong to this saint but actually to someone who lived 160 to 240 years later. This research thus once again illustrates the burgeoning practice of transporting bones in the early Middle Ages. The study was carried out by an international team of scientists, including Prof. Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (affiliated with the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome, KNIR) and Prof. Hans van der Plicht (expert in the field of carbon-14 dating) at the UG.

The Roman Santi Apostoli church has since the sixth century AD held relics, believed to be the remains of two of the earliest Christians and Jesu apostles: St. Philip and St. James, sometimes also called the Younger – relics of the Holy Catholic Church. Now, they have undergone scientific analysis, casting light on their age and origin.

Remains of martyrs

Despite its difficult time during the first centuries, from the fourth century onwards Christianity gradually became the dominant religion. After Emperor Constantine on his deathbed declared Christianity the state religion, churches were erected all over Italy and in Rome. Shortly after the churches were erected, remains of worshipped Christian martyrs were moved from their graves to designated worship churches in the towns. This also applied for the remains of the two apostles, St. Philip and St. James. Such movements of remains were called translations.

A foot, a femur and a tibia

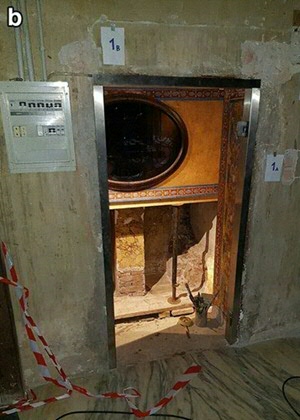

It is unknown who transferred the alleged remains of St. Philip and St. James and where from, but it is a fact, that they came to glorify the current church of Santi Apostoli in Rome, constructed in their honor. It is also a fact that the remains have been kept in the church since the sixth century. So, are the relics really the remains of St. James and St. Philip? And what else can we learn from the bones? The skeletons are today far from complete. Only fragments of a tibia (shinbone), a femur and a mummified foot remain. The tibia and foot are attributed to St. Philip, the femur to St. James. It appears likely that this has been the case since the sixth century.

Femur not from St James

The researchers considered the remains of St. Philip too difficult to de-contaminate and radiocarbon date, and their age thus remains unknown so far. But the femur, believed to belong to St. James, underwent several archaeometrical analyses. Most importantly, it was radiocarbon dated to AD 214-340. Thus, the femur is not that of St. James. It originates from an individual some 160-240 years younger than St. James. Nevertheless, it casts a rare flicker of light on a very early and largely unaccounted for time in the history of early Christianity.

Looking for remains

It is considered very likely, that whoever moved this femur to the Santi Apostoli church, believed it belonged to St. James. They must have taken it from a Christian grave, so it belonged to one of the early Christians, apostle or not. The same goes for the believed remains of St. Philip. One can imagine that when the early church authorities were searching for the corpse of the apostle, who had lived hundreds of years earlier, they would look in ancient Christian burial grounds where bodies of holy men might have been put to rest at some earlier time, the researchers write in Heritage Science.

Moving bones - a popular tradition

The first historically known movement of a martyr’s remains to a church is that of St Babylas in AD 354. His remains were transferred from a cemetery in Antioch to Daphne and placed in a church especially built for the purpose by Governor Caesar Gallus. Immediately after this, translations became popular: the translations of St Timotheus, St Andrew, and St Lukas to Constantinople followed in a year’s time. At the same time, sources reflect an increasing popularity and circulation of relics from the second part of the 4th century onwards. Despite the criticism of bishops, throughout the Roman empire bodies or body parts were exhumated, transferred, and reburied in the apse in close vicinity of the altar of many important churches.

International team

The research was done by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Groningen, University of Pisa in Italy, Cranfield Forensic Institute in England, Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology in Italy and the National Museum of Denmark. The lead investigator is prof. Kaare Rasmussen from Odense. Groningen participants are prof. Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta from the Faculty of Religious studies, and prof. Hans van der Plicht from the Faculty of Sciences and Engineering who performed the Radiocarbon dating.

The results have been published in the scientific journal Heritage Science (including photos).

Contact

- Kaare Lund Rasmussen, klr@sdu.dk

- Hans van der Plicht, j.van.der.plicht@rug.nl

- Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta, f.l.roig.lanzillotta@rug.nl

| Last modified: | 01 February 2021 07.40 a.m. |

More news

-

03 April 2025

IMChip and MimeCure in top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition

Prof. Tamalika Banerjee’s startup IMChip and Prof. Erik Frijlink and Dr. Luke van der Koog’s startup MimeCure have made it into the top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition.

-

01 April 2025

NSC’s electoral reform plan may have unwanted consequences

The new voting system, proposed by minister Uitermark, could jeopardize the fundamental principle of proportional representation, says Davide Grossi, Professor of Collective Decision Making and Computation at the University of Groningen

-

01 April 2025

'Diversity leads to better science'

In addition to her biological research on ageing, Hannah Dugdale also studies disparities relating to diversity in science. Thanks to the latter, she is one of the two 2024 laureates of the Athena Award, an NWO prize for successful and inspiring...