Whatever you do, don’t humanize care robots

In the future, robots will play an important role in our everyday lives. In the healthcare sector, for example, an extra pair of hands is always welcome. But whatever you do, please do not give these robots a name or a human face, warns Professor Jenny van Doorn. Surrogate people make us feel uncomfortable, resulting in all sorts of consequences.

Text: Riepko Buikema, Communication Office; Photos, Elmer Spaargaren

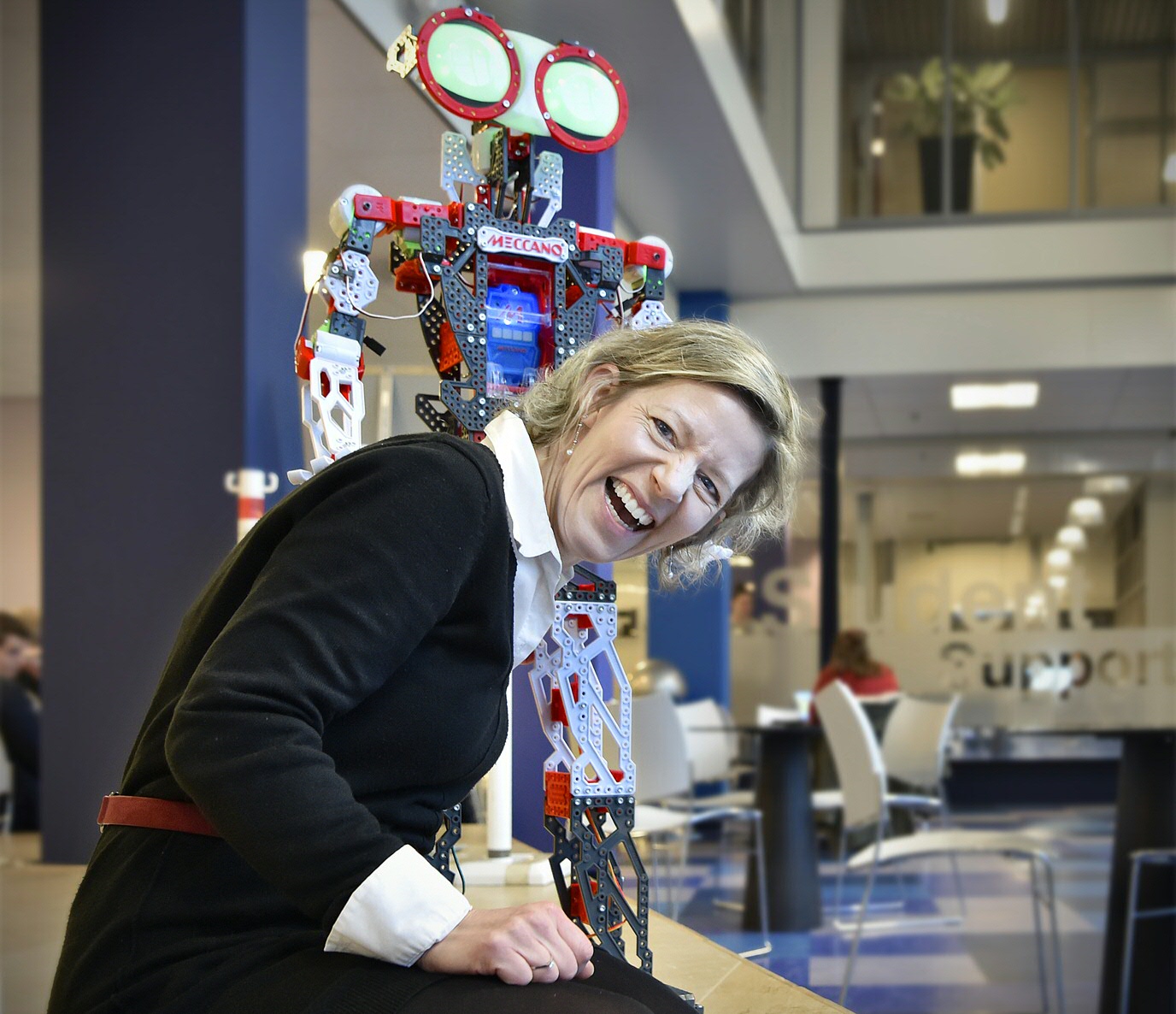

I received a hilarious message from the photographer after his shoot with Jenny van Doorn: ‘Her robot is like a stubborn toddler. It tried to give her a high five, but it went wrong! It hit Jenny on the ear and it knocked her earring off onto the floor...’

This incident perfectly echoes the words of marketing expert Van Doorn earlier that week. Although marketers generally have no trouble speaking about their research projects in glowing terms, her comments on the current possibilities and limitations of service robots were rather sober.

Limited value

‘To be honest, most robots can’t do that much yet,’ says Van Doorn. ‘In Japan, you come across them a lot when you’re out shopping, but they don’t do much more than say hello and give some basic information. The value of robots is still fairly limited, especially given the considerable costs involved for programmers. It’s not a coincidence that the Hilton hotel chain stopped its experiment with Conny, the robot concierge. There are still many unanswered research questions in this area: What’s the best way to use a robot? How do people react to them? How should humans and robots work together?’

A disappointed robot

My own collaboration with the huge toy robot in the corner of Van Doorn’s office wasn’t exactly plain sailing. The robot is called Meccanoid and he (or she) has been designed to teach children how to program. ‘My children know him from Mr Sjoerd’s year 7 class,’ says Van Doorn, ‘but I use this robot for my research.’ When Van Doorn briefly left the room to talk to someone, I just couldn’t resist. ‘Give me high five!’ I said, after a quick browse through the manual. And the plastic hand reached out into the air! But I hit it too softly, which really seemed to disappoint Meccanoid. ‘Oooohhhh, high five denied!’

Threatening

Van Doorn is fascinated by this interaction between robots and humans – by not only the complex technical translation of verbal tasks into action, but also the social consequences of services provided by artificial aids. Because it turns out that humans react negatively to robots. ‘I didn’t expect that beforehand, but nearly all studies have shown that to be the case,’ says Van Doorn. ‘When robots replace a waiter or receptionist, we often find it a bit creepy and experience it as a threat to our identity. It causes us more stress and discomfort than when we have to deal with a human worker.’

Ordering more food out of unease

The unease we experience when interacting with a robot presents an additional problem. In the experiments conducted by Van Doorn and her colleagues, to compensate for the unease experienced when being served by a service robot, participants ordered more food (especially unhealthy food) or bought more expensive, status-enhancing items.

Like when we’re feeling a bit down at home and reach for the chocolate? ‘Yes, it’s exactly the same thing!’ says Van Doorn with a laugh. ‘Exactly the same.’ Van Doorn published her sensational findings in the scientific article ‘Service Robots Rising: How Humanoid Robots Influence Service Experiences and Elicit Compensatory Consumer Responses’, a copy of which hangs proudly on her office door.

Balancing act

For marketers, the proven effect is a double-edged sword, Van Doorn admits. ‘From a business point of view, it’s good that people order more or buy more expensive items, but things are bound to get difficult if customers feel uncomfortable using your services.’ And don’t come to Van Doorn with the assertion that marketing is only about generating more and more sales. ‘My work has to be relevant to society, otherwise I don’t really see the point. For example, we can also use our knowledge to combat food waste or to help adapt robots for supportive tasks in the healthcare sector.’

Staff shortage

Despite her reservations, Van Doorn sees the greatest potential for robots in the healthcare sector. ‘So far, my research has shown that people are not always very enthusiastic about robots. I have also shared these findings with healthcare workers. I’m honest with them and say: “Look, the elderly think it’s all very interesting, but they are not very positive about the use of robots.” Then they tell me: “That’s good to know, but we have to press on with it anyway. Otherwise we won’t be able to cope with staff shortages in the future.”’

Unaffordable

Van Doorn has experienced this situation first-hand. ‘My mum and aunt cared for my grandma; they were her care system. They took turns staying with her. In such cases, a technical solution might not be so bad.’ Through her colleague Jochen Mierau and the Aletta Jacobs School of Public Health, she was introduced to a German professor in Oldenburg who is working on a system of smart speakers and home automation solutions that send people with dementia back to bed when they get up at two in the morning and get dressed. ‘Such intensive supervision is already virtually unaffordable with normal human carers. I see it as my duty to explore how we can use robots without unduly compromising patients’ care experience.’

Don’t give the thing a name

Van Doorn discovered that a number of adjustments reduce the unease experienced during interactions between robots and humans. For example, she is dead set against the tendency to humanize robots. ‘We have shown that robots shouldn’t be given a name or a real voice. We also seem to feel more comfortable in situations where a robot provides the service in cooperation with a real human being. I also just want to make very clear that this robot here next to me is a machine; he is the assistant and I am in charge. That’s a very tangible result of our research.’

Remove your earrings!

Van Doon will be explaining more about this research and her expectations for the future with regard to services on 3 March, during her inaugural speech “Frightful or fantastic?”. House robot Meccanoid will also be accompanying Van Doorn in the Aula of the Academy Building. Warning: remove your earrings!

More information

- Contact: Jenny van Doorn

- 3 March 2020, 4.15 p.m., inaugural lecture by Van Doorn: ‘En(i)g? Robots en kunstmatige intelligentie in de dienstverlening

- Publication in the Journal of Marketing Research: Service Robots Rising: How Humanoid Robots Influence Service Experiences and Elicit Compensatory Consumer Responses

| Last modified: | 01 February 2023 4.21 p.m. |

More news

-

01 April 2025

UGBS Executive MBA best-rated MBA | Dutch Master's Guide 2025

According to the independent Keuzegids Masters 2025, the Executive MBA of the University of Groningen Business School is the best rated MBA in the Netherlands (both part-time and full-time programmes).

-

01 April 2025

Executive Master of M&A and Valuation accredited as joint degree with Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Starting 1 September, participants enrolled in the programme will receive a master's degree from both the University of Groningen and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam upon successful completion.

-

24 March 2025

UG 28th in World's Most International Universities 2025 rankings

The University of Groningen has been ranked 28th in the World's Most International Universities 2025 by Times Higher Education. With this, the UG leaves behind institutions such as MIT and Harvard. The 28th place marks an increase of five places: in...