Riding the waves of science

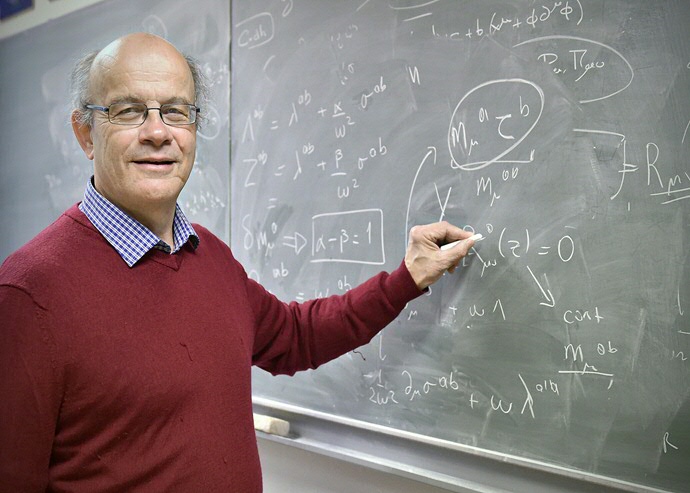

No one has been able to prove Einstein wrong. A change of scenery gives you new ideas. It is highly unlikely that a Theory of Everything will ever be constructed – which is good, because understanding everything would be boring. These are just a handful of statements from an hour with Professor of Theoretical Physics Eric Bergshoeff.

Text: René Fransen / Photos: Elmer Spaargaren

Getting an appointment with Eric Bergshoeff is a bit difficult, as he is on a sabbatical that involves spending two months at a time at three different research institutes. Having visited Vienna and Paris, he is briefly at the University of Groningen before flying to Canada on 1 April, to spend the next two months at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics.

The inspiration of travel

‘Travel and dialogue have always been important to me’, says Bergshoeff in his room in the Physics and Chemistry building at the Zernike Campus in Groningen. ‘Just sitting at my desk here creates a routine. Travel breaks that routine, and you meet new people. I need that to get fresh ideas.’ When he is not travelling the world, cycling home from the university can do the trick as well. ‘The other day, I was discussing a problem with one of my students. But it was only as I was cycling home that the answer popped into my head. I will meet her later today to discuss it.’

Being like Einstein

The issues he discusses usually have to do with gravity. Although we all experience how gravity works, the theory behind it is still a bit of a mystery. ‘There is Newton, who describes ordinary gravity at low speeds, and Einstein’s General Relativity, which works at relativistic speeds. But how we get from Einstein to Newton and back is not so clear.’ Take the newly discovered gravity waves, generated by the fusion of two black holes: these are the result of such a non-relativistic event. ‘This discovery has really stirred things up’, says Bergshoeff contentedly. Einstein inspired him to study physics: ‘I liked physics at school, and what I learned about Einstein made me want to be like him.’ Watching the moon landings and gazing at the stars also stirred his sense of wonder, and his curiosity.

Holy Grail of theoretical physics

As a student he spent time in the physics lab, but discovered that theory was more to his liking. The kind of theory that Bergshoeff got involved in is quite complicated and not always easily translated into experiments. String theory was all the rage then. It described fundamental particles as two-dimensional vibrating strings. In a seminal paper he wrote with two colleagues in 1987, Bergshoeff suggested these strings might actually be 11-dimensional membranes. These kind of string or membrane theories have long been seen as possible solutions to the unification of quantum theory and gravity problem. ‘That is more or less the Holy Grail of theoretical physics’, says Bergshoeff. ‘But I don’t think that unification will happen, that we will discover a “Theory of Everything”.’ And that is not a bad thing, he adds: ‘It is exciting to discover new things. Wouldn’t it be boring if we knew everything?’

Scientific surfing

Bergshoeff has seen theories in his field spawn new branches, some of which withered while others flourished. ‘Our knowledge has increased a lot. We know so much more about cosmology, the Big Bang. New ideas may be obsolete in ten years’ time.’ But as our knowledge grows, new questions arise. ‘What we don’t know is sometimes a bit of an embarrassment.’ For example, cosmology models depend heavily on dark matter and dark energy, but physicists don’t know what these are. So how does science work? ‘I see the development of science as a series of waves. If you are in the right place at the right time, you catch a wave which will propel you forward. But then it can peter out, and you may have to wait for the next wave.’ Riding the waves takes a good brain, but not extreme intelligence. ‘You can’t say that your IQ defines you as a scientist. The time has to be ripe for new ideas.’

Societal impact

Science policy these days dictates that some type of societal impact is required of research. ‘Of course, it depends on what timescale you want’, says Bergshoeff. ‘Take the discovery of the electron. That had quite an impact on society, eventually.’ He has noticed that fields like ‘quantum information’ have the interest of the military, so a lot of money goes that way. ‘But I do feel our work should be driven by curiosity. If you put a bunch of us together and let us think, something will happen.’ Bergshoeff is known for his public engagement. ‘Many people feel the urge to understand the world they live in. And they seem to expect me to be able to explain things.’ He gives many talks, usually on themes like gravity, or the work of Albert Einstein. ‘And yes, there are always people who think they have found errors in his work. But the fact is that after a hundred years, not even one percent of his General Relativity has been changed.’ As a scientist, he feels an obligation to interact with society. ‘After all, my training and my work has been paid for with taxpayers’ money.’ But he warns that scientists shouldn’t be too eager to show how useful their work has been. ‘There have been big announcements that were subsequently retracted. That sort of thing feeds science scepticism, which is a bad thing.’

Time travel

And the world needs science, especially now. ‘I worry a bit about the speed at which society has changed during my lifetime. The dinosaurs were around for tens of millions of years. We have been around much shorter and look what we have achieved. It is difficult to imagine how life will be a thousand years from now. But I can hardly believe that things will remain stable.’ And talking of the future, there is something else he would like to know. ‘What I want for my birthday is a ticket to a physics conference, a hundred years in the future. How would they talk about this period? As the Dark Ages, or a period of discovery? It is hard to tell.’

Contact

| Last modified: | 12 March 2020 9.23 p.m. |

More news

-

03 April 2025

IMChip and MimeCure in top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition

Prof. Tamalika Banerjee’s startup IMChip and Prof. Erik Frijlink and Dr. Luke van der Koog’s startup MimeCure have made it into the top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition.

-

01 April 2025

NSC’s electoral reform plan may have unwanted consequences

The new voting system, proposed by minister Uitermark, could jeopardize the fundamental principle of proportional representation, says Davide Grossi, Professor of Collective Decision Making and Computation at the University of Groningen

-

01 April 2025

'Diversity leads to better science'

In addition to her biological research on ageing, Hannah Dugdale also studies disparities relating to diversity in science. Thanks to the latter, she is one of the two 2024 laureates of the Athena Award, an NWO prize for successful and inspiring...