Photo exhibition

1. Palestine in Transition

Scholten’s sole exhibition during his life time was called Palestine in Transition. While motivations for photo project were religious, Scholten was well aware of the changing life of Palestine. He found bustling cities that were changing rapidly, motivating much of his documentary approach to the region. Despite the religious focus of his project, the collection tells us much about modernity in Palestine, particularly processes of urbanisation, population movements and class and communal dynamics in the years that the British Mandate over Palestine was being formalised.

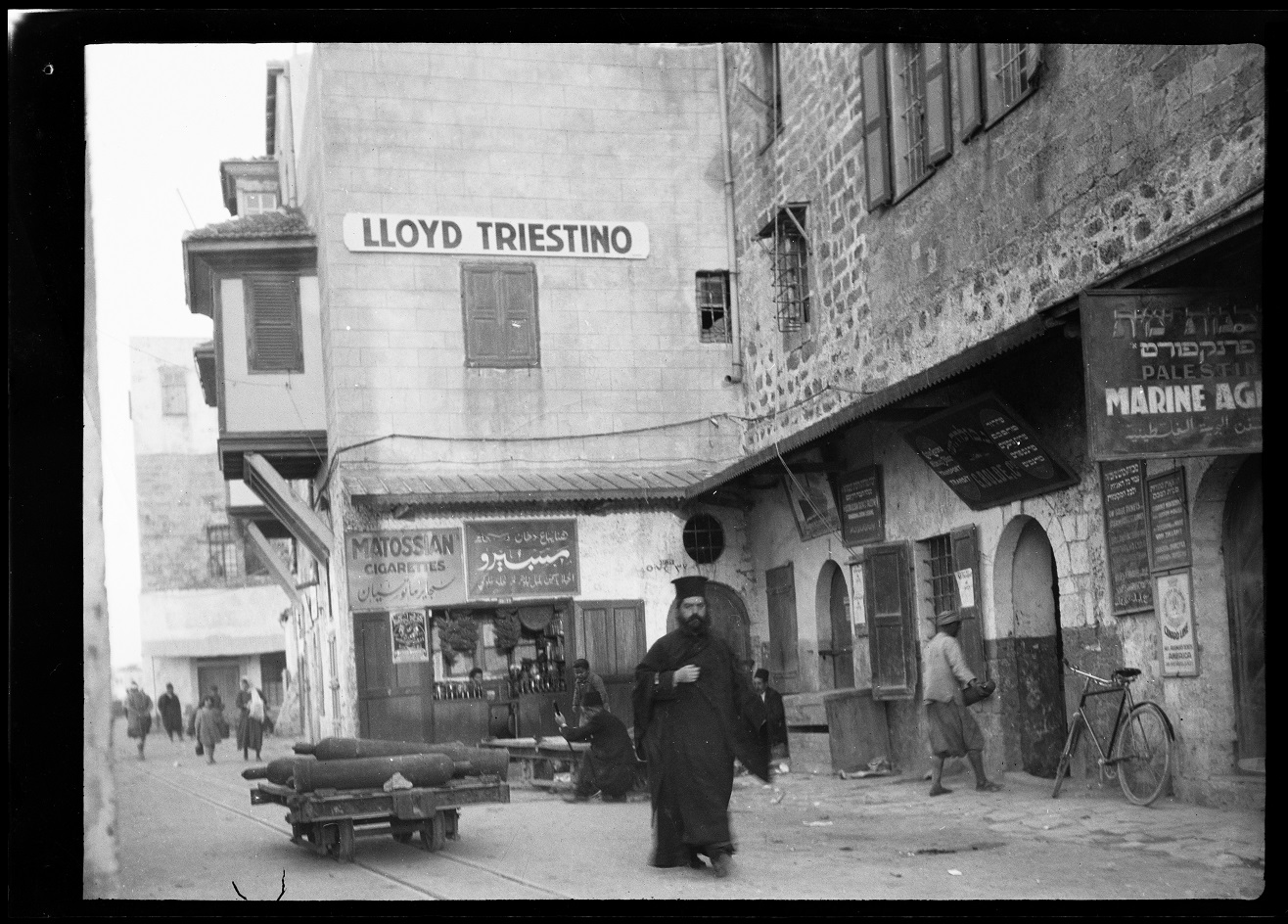

Jaffa Port, 1921-23

Scholten arrived at the port of Jaffa in early 1921. While Jerusalem held global religious importance, Jaffa was the primary economic and cultural centre, owing to its port. Trade and shipping were important to Jaffa, connecting it to other Mediterranean port cities such as Thessaloniki, Smyrna, Beirut, Alexandria and further afield to Western trading centres like Marseilles and Manchester as well as North and South America. The 1920s saw the return of many Arab Palestinian traders who had migrated in the late Ottoman period, particularly to South America, bringing new wealth back to the country.

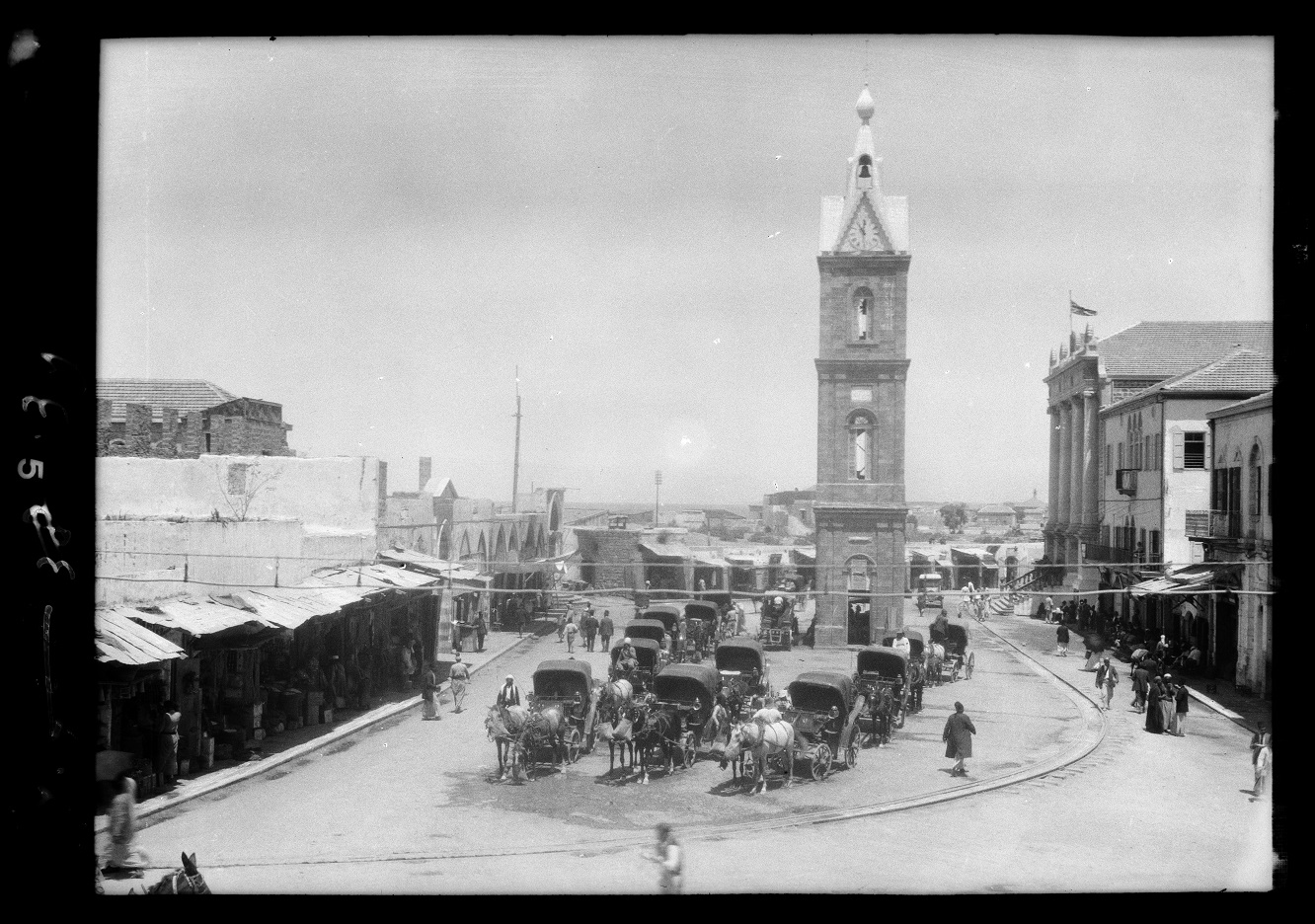

The Clocktower of Jaffa, 1921-23

Cities like Jaffa and Jerusalem changed radically in the 19th century. With Mohammed Ali Pasha’s Palestine campaign in the 1830s, the ailing Ottoman State launched the Tanzimat Reforms as a means of modernising the Empire and secularising bureaucracy. From the 1840s onwards, Palestine underwent a significant process of urbanisation, breathing new life into its ancient cities. The Jaffa Clocktower was one of many established through the empire in the early 20th century to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s rule. These clocktowers were a symbol of modernity in Palestinian cities, reflecting the agenda of the Ottoman State.

Jaffa Street in Jerusalem, looking towards the Jaffa Gate, 1921-23

With the cessation of hostilities after the First World War, business began to flourish once more. This image shows Mamilla, one of the new suburbs of Jerusalem, just outside of the Old City’s Jaffa Gate, in the well-to-do West of the city. Mamilla was a commercial centre. To the right of the image is the studio of the well-known Christian Arab photographer Chalil Raad, who studied photography under Garabed Krikorian, an Armenian, whose studio was across the road (sign not visible here). Also visible behind Raad’s studio is the sign for the Greek-Palestinian Savvides photographic studio, demonstrating the significant influence of Christians on photography in Palestine.

Christian Quarter, Old City of Jerusalem, 1921-23

Jerusalem’s Old City saw much significant restoration and renovation in the years after the war, particularly under the auspices of the British instituted Pro-Jerusalem Society. This period was fundamental to shaping the urban planning of the city as it is today, but despite the preservation carried out, well-to-do Jerusalemites continued to leave the Old City for the new middle-class suburbs in the West of the city. Modern British ideas of heritage preservation greatly impacted on the ancient quarters of Jerusalem. This was very different to the ways in which the British treated Jaffa, which in 1936 would see the Old City walls demolished and boulevards for military access cut through the ancient port city during the Arab Revolt.

2. Christianity and the Manifesting of National Presence in Palestine

Through the course of the 19th century, many European nations opened new institutions as well as building churches and other infrastructure that supported both the pilgrimage of their nationals and created spheres of cultural influence within Arab Palestinian communities. These relations were often along communal lines, for instance Russians addressing Orthodox Palestinians, or French and Italians addressing Arab Catholic Palestinians.

Scholten was, on some level at least, aware of such relations. In the two-volume set of photographic books that he published in French (1929), English (1930), German (1931) and Dutch (1935), the references change slightly in each language reflecting lingual relations and colonial affinities that had developed within each community.

The Russian Church of Mary Magdalene, Jerusalem, 1921-23

Like the institutions that facilitated pilgrimage, many nations also established new churches, such as the Russian Orthodox Church of Mary Magdalene, built in 1888. Palestinian Christians often had involvement with such churches, which had its own impact on indigenous Christians. The Halaby family, for instance, who had close relations with the Russians in establishing Mary Magdalene, produced the iconographer Khalil Halaby as well as the Palestinian modernist painter Sophie Halaby.

Many of these institutions were a form of national as well as religious representation in the ‘Holy City’, affirming the denominational status of different European nations. While they facilitated pilgrimage and tourism to Palestine, they were also nationalist endeavours that had significant programs of cultural diplomacy – often related to the arena of education – particularly among Palestinian Christians.

Garden of Gethsemane, 1921-23

While new institutions and churches continued to be built, older sites like the Garden of Gethsemane underwent renovations to appeal to the lucrative tourism industry. Here, the ancient olive trees which are said to date from the time of Christ, are landscaped into the new garden for tourists and pilgrims to visit under the auspices of the Catholic Custodia di Terra Sancta. There was much controversial competition for control of Holy Sites by the various Christian denominations, a continuity of the Status Quo agreements on their administration in the 1850s.

3. Catering to Christians: Making the ‘Holy Land’

Pilgrimage to Palestine had a long history dating back to the time of Constantine the Great. However, with the technological and cultural shifts of modern life, pilgrimage gave way to a broader industry of tourism. Multinational tourism operators such Lloyd Triestino and Thomas Cook ran tours through Palestine, which sat alongside nationalist-religious infrastructure such as the Russian Compound, the Austrian Hospice and Notre Dame. By the 1850s diaries talk of Jerusalem as a modern tourism centre, with some preferring less commercial location like the Jordan that were seen as more authentic. The transnational cultural affinities that had shaped the political subtext of Palestinian communalism were visible in the ways Arab Christians responded to discrete markets of tourists.

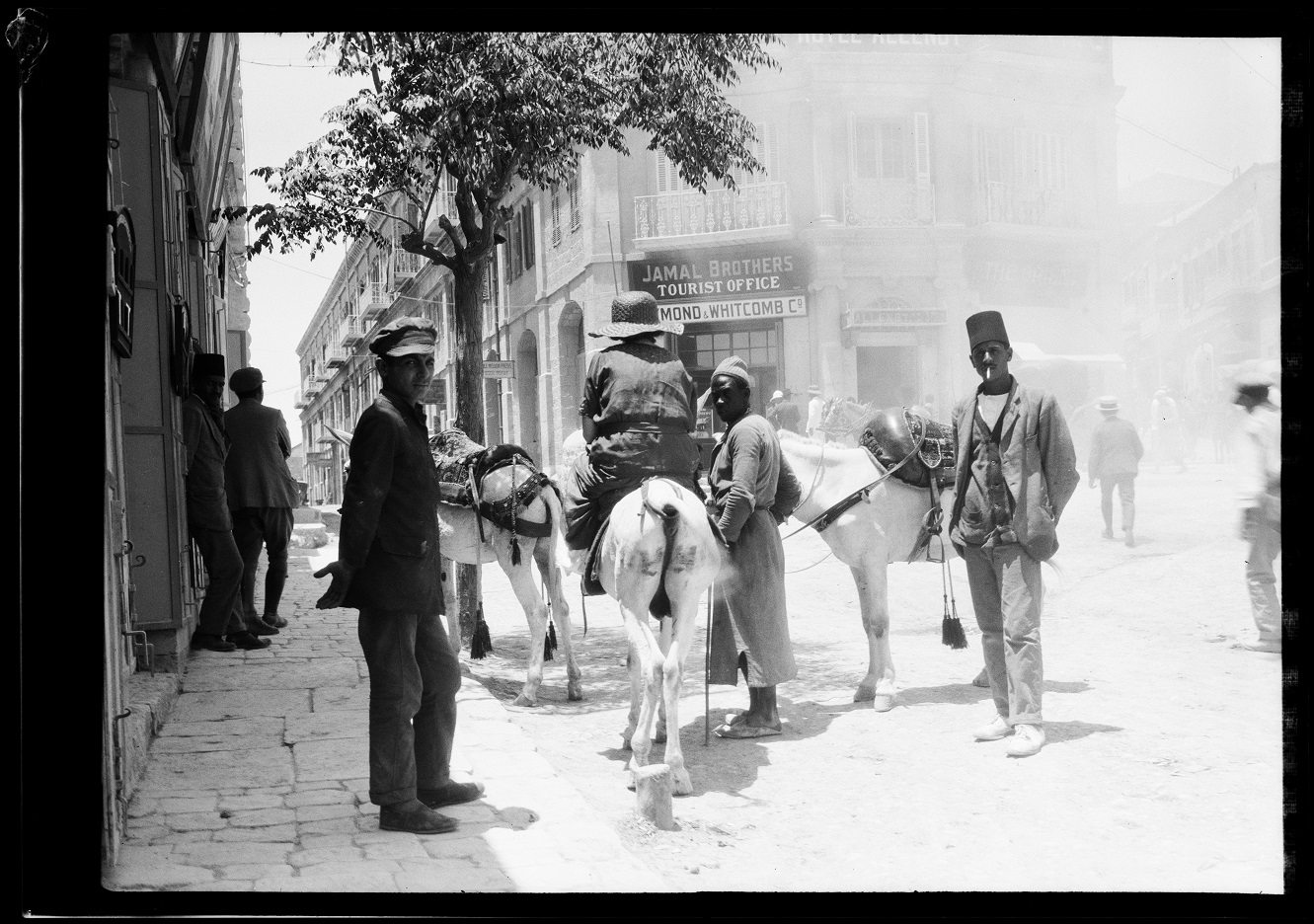

Jaffa and Jerusalem

Modern tourist infrastructure had been developed through the course of 19th century. Transnational tourist operators like Thomas Cook and Lloyd Triestino developed tours, often in conjunction with local operators to service the booming industry in the interwar period.

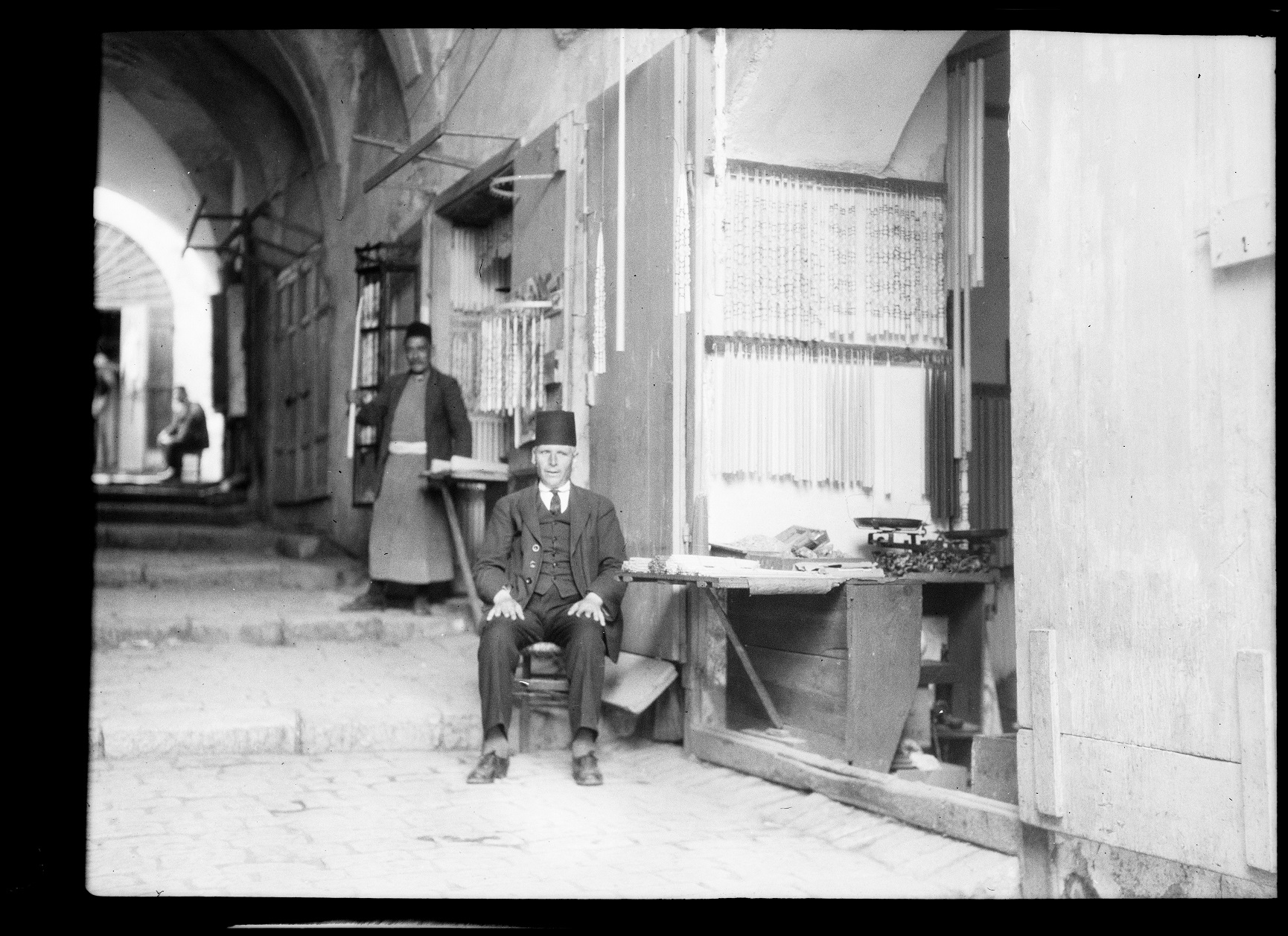

Arab Orthodox Vendors in the Old City of Jerusalem, 1921-23

Diaries from the period discuss the fact that various vendors in the pilgrimage market tended to focus their wares towards specific communities. Orthodox Palestinians tended to focus on materials for various Orthodox communities. After the Russian Revolution, the nature of such businesses began to broaden, acclimating to a reduced flow of Orthodox pilgrims, but nevertheless retained the important materials for worship such as candles. This had significant parallels with Palestinian visual art. Many artists who had traditionally produced icons began to turn to more secular modes of painting, most notable among them, Nikola Saig.

Church of the Nativity and Manger Square, Bethlehem 1921-23

Tourism and pilgrimage were also formative for Bethlehem. The city became the centre of mother of pearl carving, in addition to its significance for the birth of Christ. Pictured here are Manger Square and the front of the Church of the Nativity.

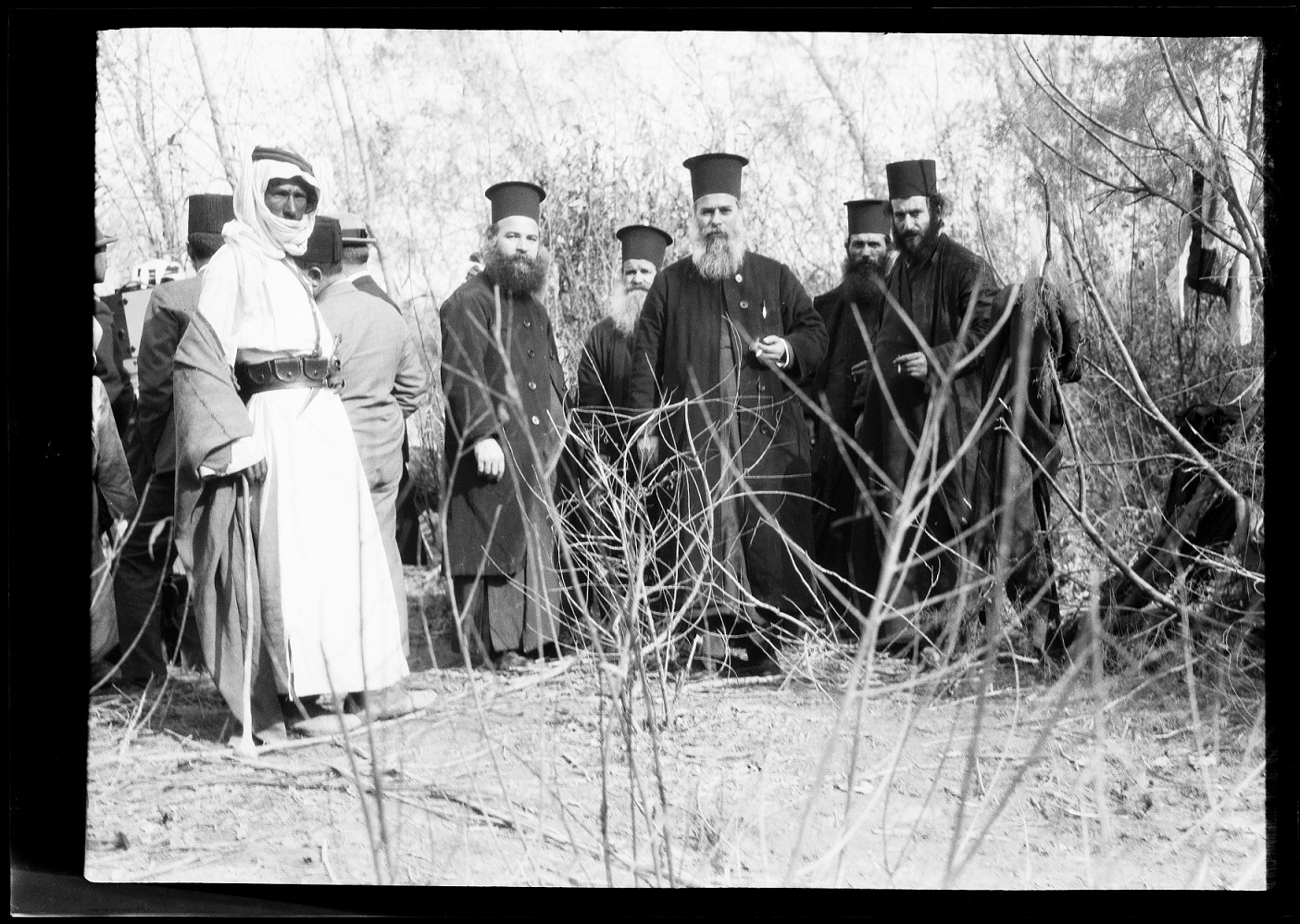

Tour guides, dragomans and Greek Orthodox priests, Jordan River, 1921-23

The organisation of pilgrimages involved many people. Here we see an Arab dragoman – an interpreter – with two urban tourist operators behind him, standing with a group of priests. The photo gives us a sense of the significant organisational infrastructure behind the planning of pilgrimages in Palestine. It also perhaps hints at some of the splits between Arabs and Greeks, given the position of priests with respect to their hosts.

4. Orthodox Communities in Palestine

The Orthodox community in Palestine was primarily Arab, though there were smaller communities of ethnic Greeks and Russians. Despite conflicts on an institutional level, on a community level there was much cordiality and intermarriage. Added to these communities were other branches of Orthodoxy, such as Syriac, Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox, with their own distinct traditions.

A young Palestinian Orthodox girl celebrating Easter, Jaffa 1921-23

One of the iconic Scholten images, this image shows an Arab Greek Orthodox girl at Easter in Jaffa. Arab Orthodox in Palestine came from a range of backgrounds, but as a result of Ottoman policy, many lived in urban centres and those from villages and rural areas often migrated to cities with the economy changes from the 1850s onwards. This photo is taken in Jaffa’s Old City, likely on Easter Sunday after the church service.

In this period around 10% of the Palestinian population were Christian, about half of whom were Orthodox. Most Christian Palestinians were historically of Orthodox background, but with the Crusades, and later missionaries, there was a growing number of Catholic and Protestant Palestinians. Most Christians lived in cities like Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, Nazareth or Bethlehem, though there were also smaller Christian towns and villages.

Orthodox Easter, Jaffa, 1921-23

For Orthodox Palestinians, Easter was the major religious celebration of the year. Here a family can be seen with candles decorated for Palm Sunday. For younger family members, palm fronds would be woven into a series of baskets on the central stem and filled with flowers as part of the festive procession. Of particular note in this image is the ways in which tradition and modernity intermingle. On the one hand, fashionable modern clothing like boater hats and Sunday bests, on the other, the enamelled locket in the traditional Palestinian style with an image of Virgin Mary around the baby’s neck.

While much of Palestine’s Orthodox community were Arab, there was a community of ethnic Greeks who intermingled with their Arab coreligionists. Relations were cordial and intermarriage was not uncommon. While the modern Greek State had been founded a century earlier, there were still many Greek communities living in the former Ottoman Empire and places like Egypt. Rising nationalism through the 20th century would see many of these communities leave for Greece, first with the Greek-Turkish population exchanges in 1922-23 and then with Arab nationalism under Egypt’s Gamal Abdul Nasser after World War II.

With the influx of missionaries and educational institutes from Western Europe and the controversial state of Orthodox church affairs, some Palestinian Orthodox began to convert to Catholicism or Protestantism. This had been a significant concern for the Russian Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society before the Russian Revolution and First World War. The Russians had intervened in the Orthodox Patriarchate supporting Palestinians demands to Arabise the Church. The Russian Revolution changed the political trajectory radically, and through the 1920s the historical links between Russia and Orthodox Palestinian saw a new generation secular and leftist Palestinians develop. This relationship had a significant impact on the nationalist agendas of Orthodox Palestinians.5. Between Communalism and Nationalism

The 1920s were a time of much political change. The confluence of the Nahda (Arab Awakening or Renaissance), Jewish and Zionist immigration, the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the British Mandate galvanised Arab identity in new ways. For Orthodox Palestinians, this meant a cultural shift in focusing on Arab identity over communal identity. The significant participation of Arab Orthodox in the broader nationalist movement, particularly in the cultural arena like the press, literature and the arts, saw the building of durable alliances between Christians and Muslims, in stark contrast to the situation of population exchanges between Greece and Turkey.

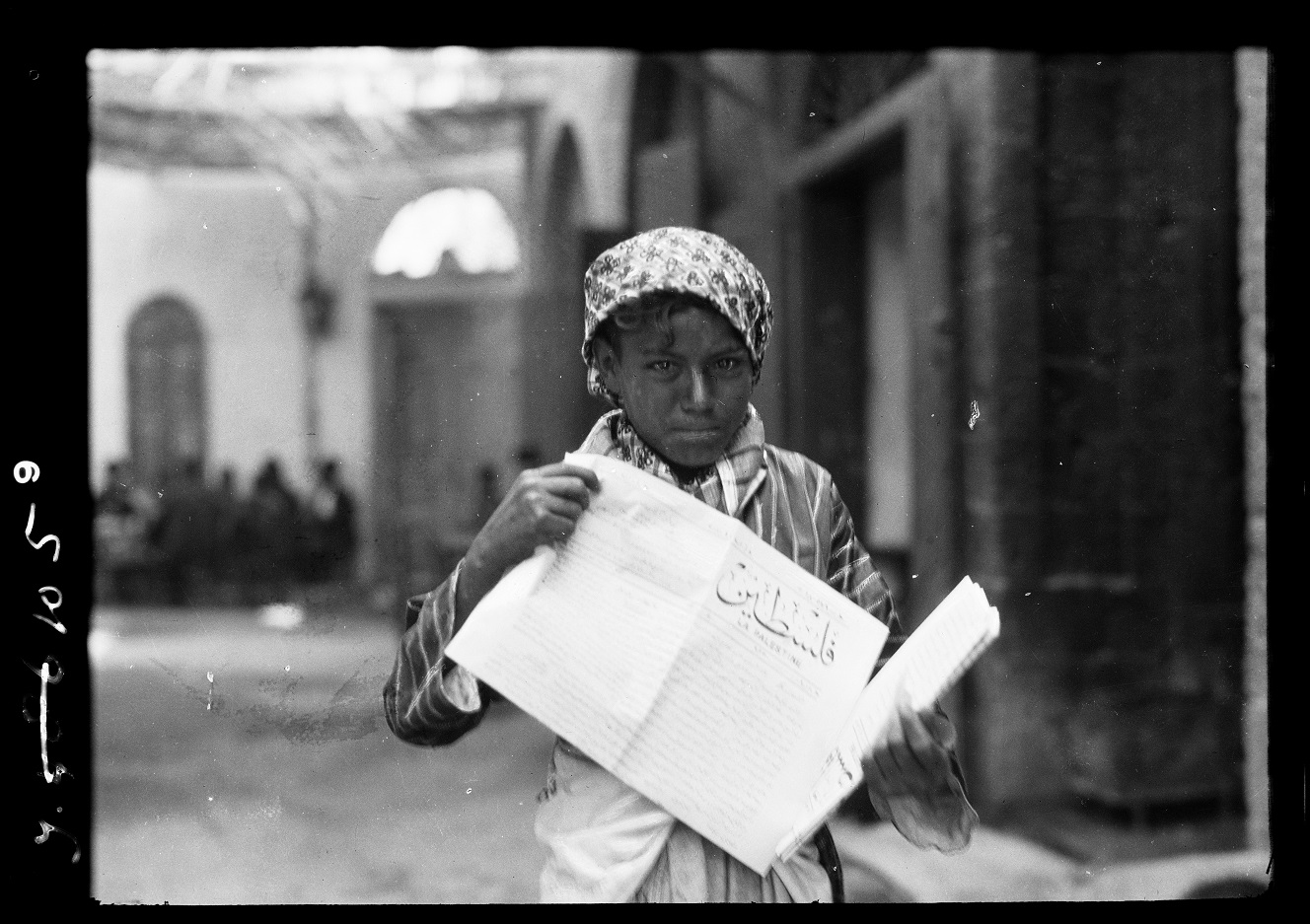

A boy sells copies of La Palestine in one of the modern neighbourhoods of Jaffa, 1921-23

Another of Scholten’s iconic images, the newspaper boy, demonstrates how influential Falastin had become, having effects on all quarters of Palestinian society. Here a young newspaper boy sells papers in the fashionable new suburbs of Jaffa. Such images show an Arab iteration of modern life in the 1920s, but also how media played a significant role in mediating Arab nationalist affairs across different class and confessional groups. It also demonstrates how the Orthodox community was heavily involved in the broader Arab nationalist struggle, marking a prioritisation of national over communal identity.

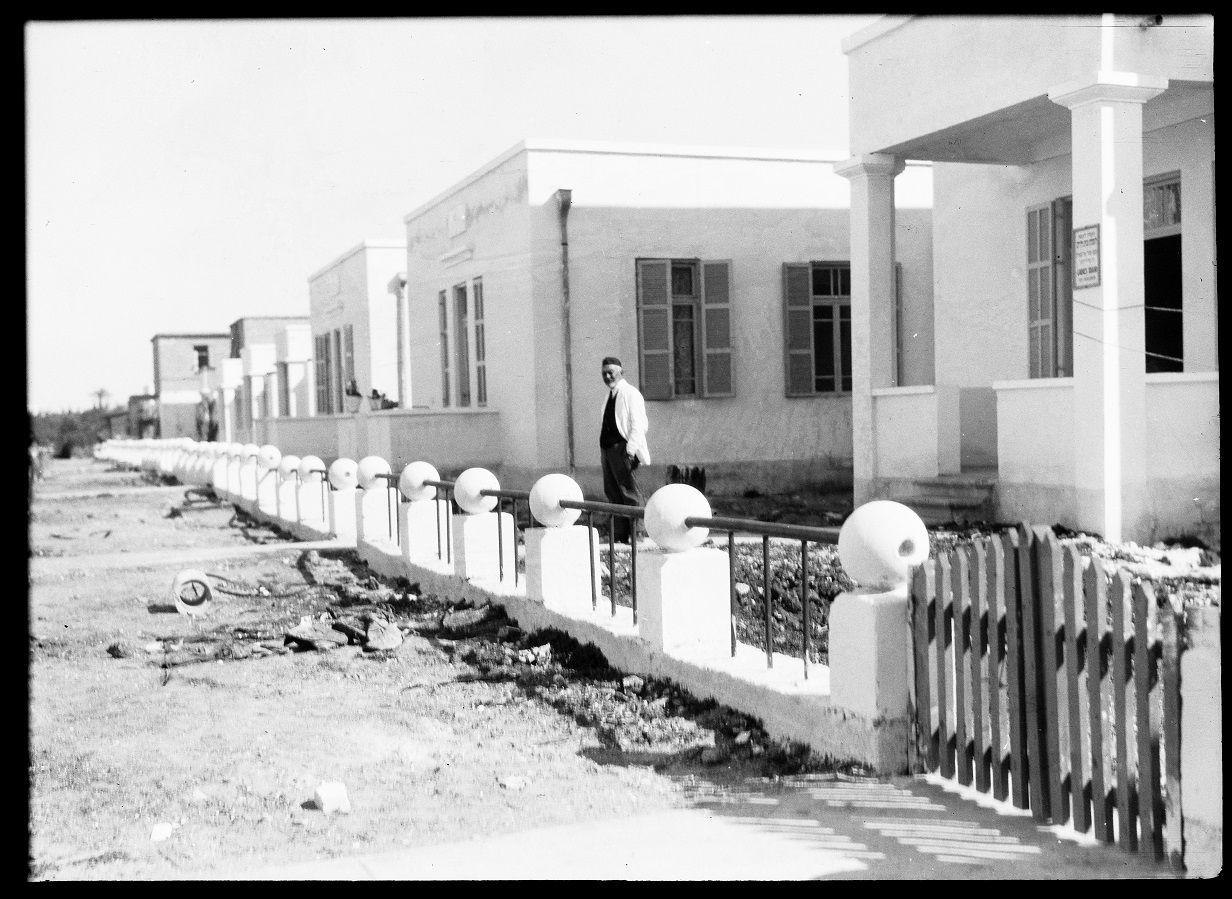

Tel Aviv, 1921-23

Much as the conflicts with the ethnically Greek hierarchy of the Jerusalem Patriarchate had significantly shaped communal relations for Arab Orthodox, the Third Aliyah (wave of Jewish migration) had a significant impact on nationalism. By the early 1920s Tel Aviv, established as a new Jewish housing estate on the outskirts of Jaffa in 1909, began to grow into a city. The Third Aliyah and its Zionist ideology, resulted in new Jewish administrative infrastructures such as the Histradut (Labour Federation), effectively galvanising Arab nationalism in the years after the Balfour Declaration (1917).

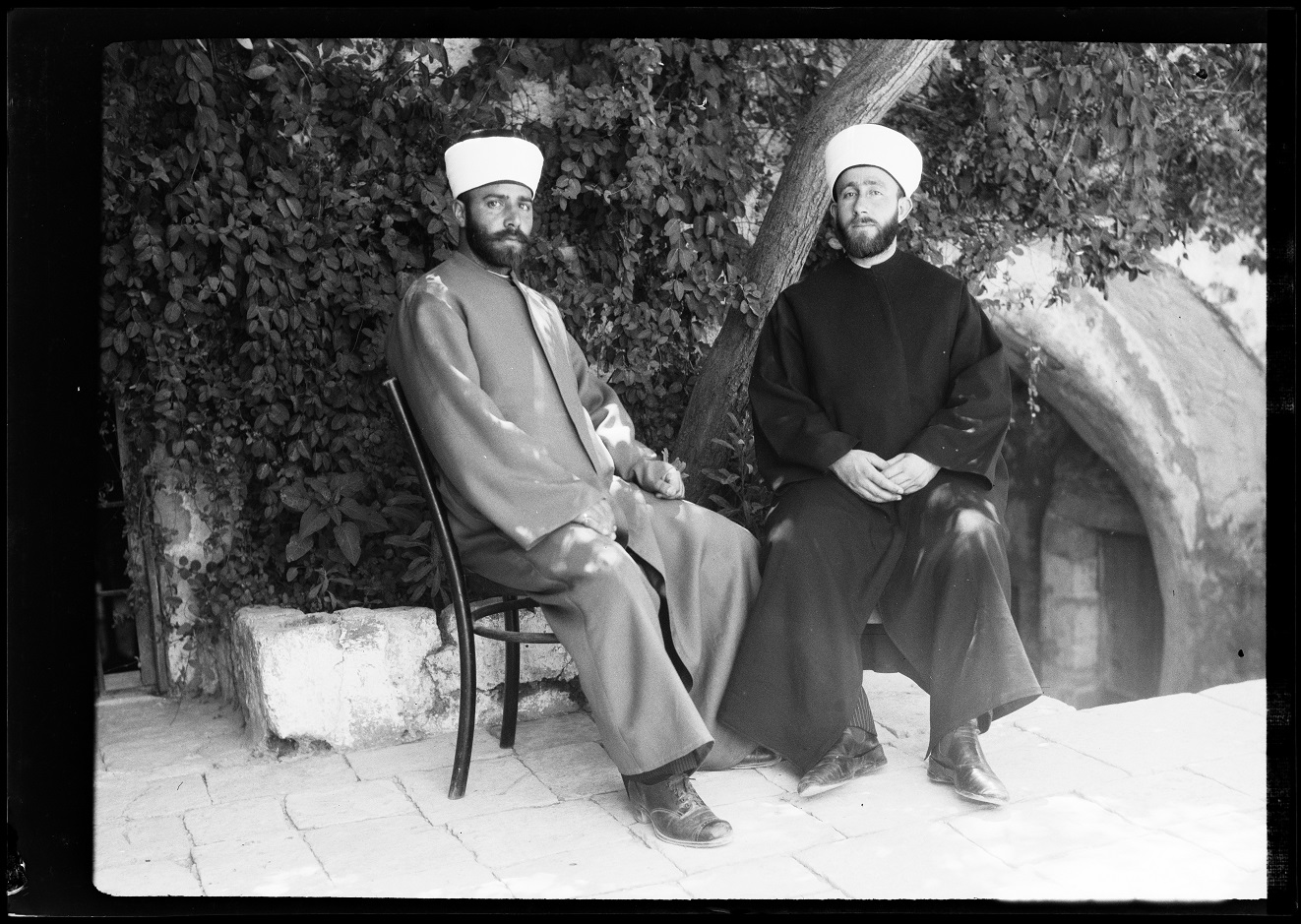

Photo of Yacoub Boukhari and Haj Amin Husseini, Jerusalem, 1921-23

Yacoub Boukhari (left) was an influential Sufi in Jerusalem, who head the Naqshbandi Wali. Mohamad Amin Al Husseini (right), was from the influential Husseini family. In 1929 he would succeed his brother as the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and become one of the most influential and divisive figures of Arab nationalism in Palestine.

This photo is taken in the years before he became Grand Mufti, but it demonstrates his career trajectory. Christians were divided on whether to support the Husseini or the Nashashibi family who both took different Arab nationalist stances. Aal Isa, for his part, had sided with the Husseini camp.

The Nabi Musa (Prophet Moses) Festival, Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem 1921-23

The Nabi Musa festival (Prophet Moses Festival) was significant Muslim religious holiday in Palestine. It is the only Muslim festival to be held according to the Christian calendar, a week-long festival commencing on the Friday before Good Friday of the Orthodox Easter. The festival would start in Jerusalem with a procession to the Nabi Musa shrine in a village of the same name near Jericho. This image is taken at the Old City’s Jaffa Gate.

In the 1920s, it transformed from a religious festival into a nationalist expression after the Nabi Musa Riot in 1920. Christian Palestinians began to take part in the Nabi Musa procession with the rise of Arab nationalism. This had parallels with Muslims taking part in the Feast of St George, in the village of Al Khader (St George), near Bethlehem.

Nabi Musa Festival, 1921-23

While there were important political shifts going with Nabi Musa, there was also a social aspect too it as well. Festivities included entertainments such as the Sunduq al Ajab (‘raree’ or ‘peep’ show), Ferris wheels, foods and drinks, making it a sociable as well as political occasion. Even for rural Palestinians, modern technologies such as the Sundaq al Ajab were transforming the ancient landscape, paralleling the broader shifts in society.

| Last modified: | 17 October 2023 1.42 p.m. |