The Marriage of Jacob Cats

When I happened by chance to come across three different copies of Jacob Cats’ 1625 Hovwelyck (also referred to as Houwelyck or Hovwelick), I thought I would make use of this opportunity to show that copies of seventeenth-century editions often present small and larger typesetting differences. It was not unusual for a printer to make changes in the process of printing a single edition. When can we speak of different editions, each deserving its own catalogue description?

Hovwelyck (or ‘Marriage’) offers a good indication of how people living in the seventeenth century viewed marriage. Over the course of six chapters, Cats tracks a human life, expounding on the appropriate behaviour for a woman through all stages of her life: as a virgin, spinster, bride, housewife, mother, and widow. The result is an edifying tale that is told in verse but is accessible for a wider audience. It was a popular book of which 50,000 copies were sold, according to the publisher .

The University of Groningen Library possesses three copies from 1625 that were originally linked to a single title description in the catalogue.

- 'EP'EP E 205 2 (hereafter A)

- 'EP'EP E- 14 (hereafter B)

- KW B 302 (hereafter C)

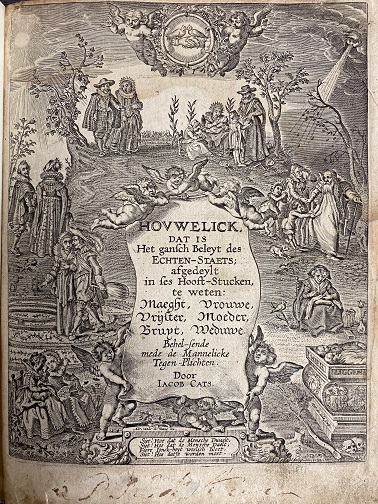

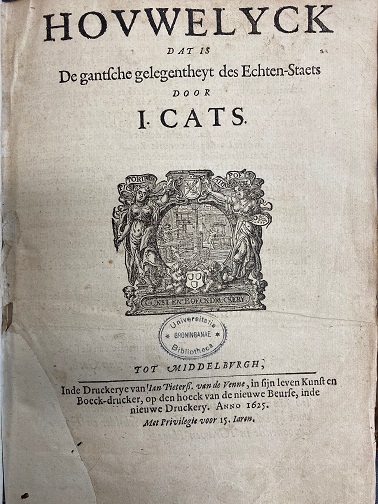

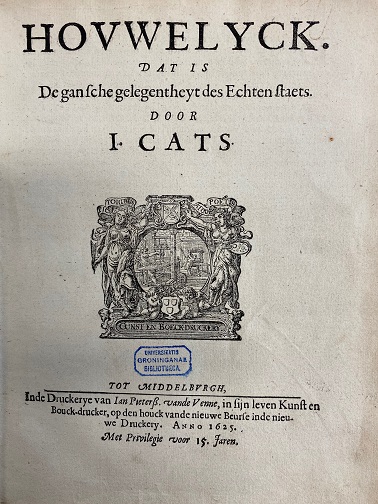

I wanted to investigate whether these three books should indeed be captured under one description. I first compared A and B. Both editions have both a typographical title page and an engraved title page (or frontispiece), as opposed to C, which only has a frontispiece. In addition to a ‘normal’ (typographical) title page, books published between the sixteenth and nineteenth century often have a separate frontispiece, usually a beautiful engraving related to the book’s content. Some books, such as C, only have a frontispiece. The book’s title can be derived from the frontispiece or copied from an identical copy with a title page. A good source for checking this is the Short Title Catalogue Netherlands. C turns out to be identical to the KB National Library's digitized copy with shelf mark 477 C 33.

I immediately noticed that the title pages of A and B were slightly different. The title and subtitle of A contain no full stop while those of B do end with a full stop. In addition, A contains the words gantsche and Echten-Staets, which are spelled gansche and Echten staets in B.

Additional typographical differences can be observed on the imprint: Boeck-drucker versus Bouck-drucker, hoeck van de versus houck vande, Iaren versus Jaren, and the word nieuwe appears in its entirety on the next line in A.

One factor that makes the comparison even more difficult (and this happens on a regular basis with early-modern prints) is that a book’s quires are not always bound in the same order. Binding happened, of course, separate from the printing process. For example, the title page of the third chapter (bruyt) in A appears after the prefaces, the frontispiece of B appears between the prefaces, A contains a portrait, and the section entitled Aende bruylofs-gasten appears at the start of the fourth chapter (vrouwe) in B, but after the fifth chapter (moeder) in A.

None of these discoveries are very exciting as yet, as they only concern two different issues. One of the two books was probably printed later than the other, and the printer created a new title page while reusing the remaining quires and placing them after the new title page. The binder then went on to bind the quires in a different order. Also, the fact that a portrait appears in one copy but not the other does not provide sufficient reason to create a new description, as such differences can easily be justified at copy level.

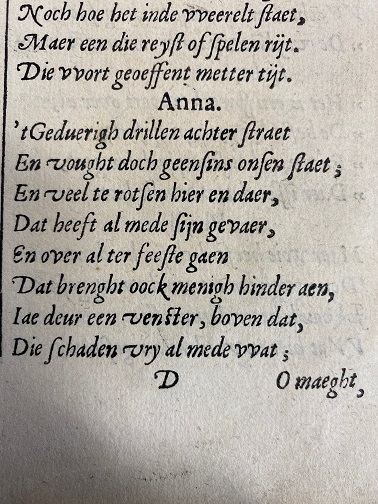

After comparing A and B, I turned my attention to C. There, I did find a striking difference in contrast to the two other copies. As mentioned earlier, this copy lacks a title page but it does contain a frontispiece. This frontispiece is identical to that of the other two copies. However, a closer examination of C reveals differences in the main text: words are typeset differently, and there are small differences in spelling and punctuation.

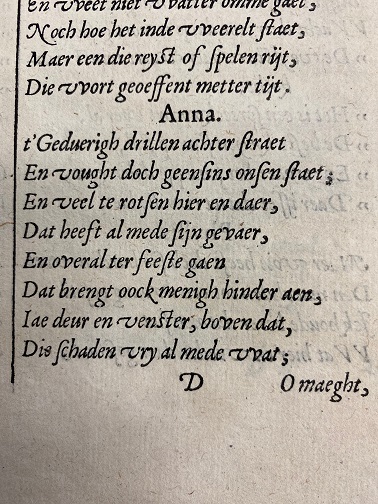

For example, in the first chapter (maeght) on page 25, third line from the bottom, C contains the word brenght while, in the other two copies, it is spelled brengt. There are also other small differences. To be able to adequately distinguish these differences in typesetting in old editions, we use what is known as a fingerprint.

However, as from the third chapter, there are no more differences between the three copies. Apparently, the printer opted for a hybrid form. He may have had enough quires left for the third chapter onwards, but not for the first and second chapter, forcing him to reprint them. Since the first two chapters each have a different typesetting, we can say that this is a different edition.

My conclusion is therefore that copies A and B are identical, although the title pages differ and the quires are bound in a different order. These are two copies of the same issue. The differences can be justified at copy level. C, on the other hand, has a different typesetting in the first chapters and is therefore a different edition. For this copy, I therefore created a new title description, complete with fingerprint.

Contrary to my original impression that I was dealing with three different editions, close inspection revealed that we are in possession of two different editions, and that the two copies of the same edition present differences on the title page and have differently bound quires. These kinds of examples are common in editions of the time. Since the University of Groningen Library possesses many old prints from the seventeenth and eighteenth century, I imagine there is a rewarding task ahead of me.

The titles can be found in our catalogue, under ‘EP’EP E 205 2 and ‘EP’EP E- 14 or KW B 302 , and they can be consulted upon request in our Special Collections research room.

| Last modified: | 12 February 2025 11.45 a.m. |