The ‘True Account’ of the Siege of Groningen

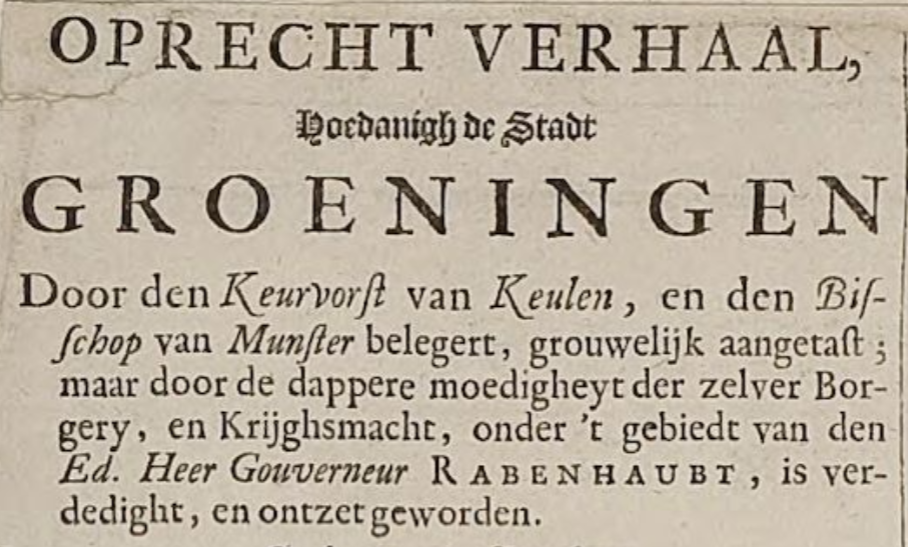

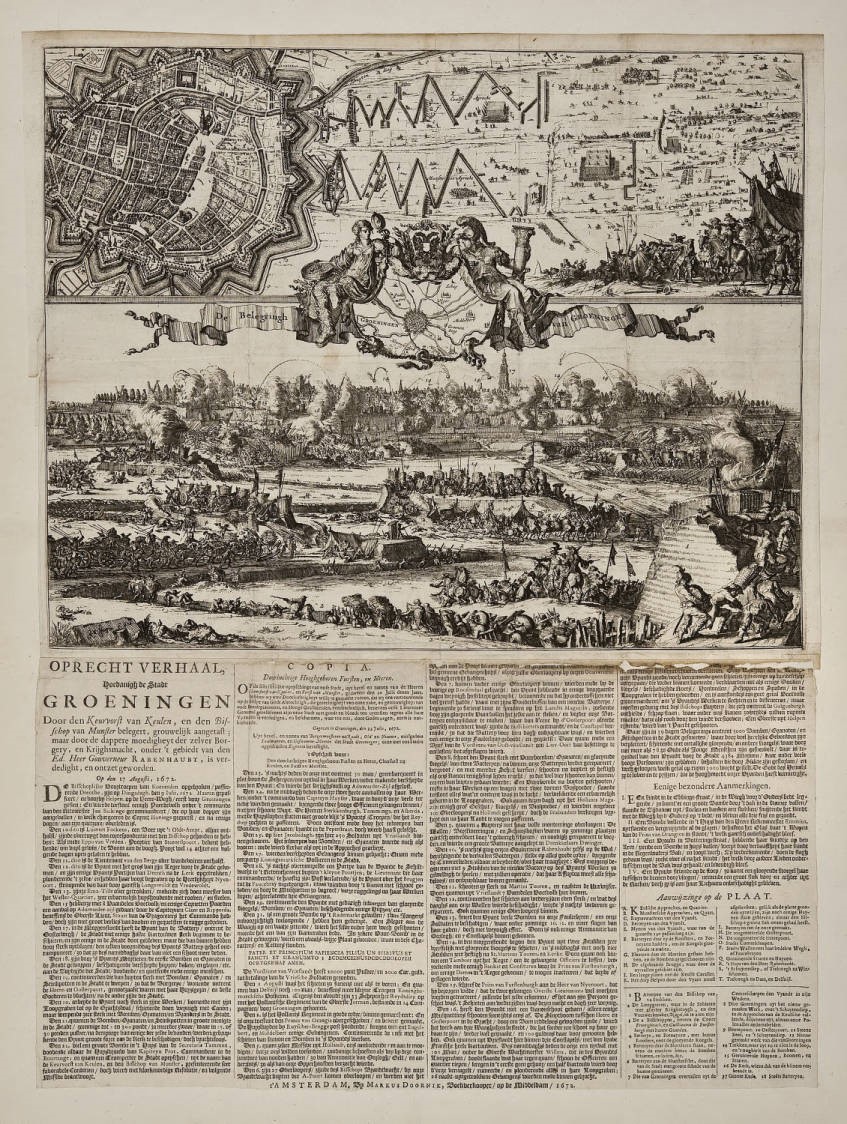

Almost immediately after Groningen was besieged by Bishop Bernhard van Galen — better known in Groningen as ‘Bombing Bernard’ —news of the Siege of Groningen spread like wildfire throughout the Low Countries. This was partially made possible by the multitude of printed pamphlets that found a ready demand among the hungry-for-news public in the cities of Holland. De Belegringh van Groeningen (‘The Siege of Groningen’) is such a pamphlet. The detailed copper engraving and accompanying text offer a chronicle of the siege. According to the pamphlet’s author, Romeyn de Hooghe , his chronicle is the ‘ oprecht verhaal ’ (‘true account’) of the Siege of Groningen. De Hooghe mapped the detailed military formations of the various parties and clearly showed, with a view of the city from behind rear lines, how the city was assailed with large numbers of bombs, grenades, firebombs, and stinkpots.

De Hooghe was an illustrator, best known today for his many illustrated title pages and newsprints. He was a politically engaged Amsterdam citizen who, according to historian Frank Daudeij, saw printing as the only ‘tegengif tegen de gecorrumpeerde kennis waarmee de toenmalige machthebbers, kort gezegd “de papen”, de inwoners van de Nederlanden probeerden te verblinden’ (‘antidote against the corrupt knowledge with which the powers of the time, in short “the Papists”, tried to blind the inhabitants of the Netherlands’). De Hooghe was an outspoken Orangist and Protestant who, according to Daudeij, saw it as his civic duty to convince his learned fellow citizens of his point of view. The production of patriotic printed material was apparently a gap in the market, as evident from the fact that during the period following the ‘Disaster Year’ of 1672, De Hooghe was one of the most wanted illustrators of the Republic, and, as is often the case with such pamphlets, he recounted recent events from a clearly ideological perspective. For details, De Hooghe usually based himself on eyewitness accounts, but since such observations were usually put to the service of his ideological message, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish rhetoric from actual events.

The fact that De Hooghe’s account, which he claims to be the only true one, is neither objective nor neutral actually becomes clear immediately. The Protestant and Republican sentiment is, for example, apparent from the introduction to his account, in which De Hooghe explains how ‘de dappere moedigheyt der zelver Borgery’ (‘the courageous bravery of the same citizens’) protected the city against the Catholic Bishop of Münster. De Hooghe describes how the city was assailed for days on end with bombs and burning bullets, and how the Stadjers (city residents) bravely endured, despite these abuses. According to De Hooghe, the Siege of Groningen provided the ultimate proof that God was on the Republic’s side, since it was ‘De Godt des Hemels … die de hooghmoedt onzer Vijanden heeft vernietight’ (‘The God of the Heavens … who destroyed the arrogance of our Enemies’).

The fact that Groningen citizens were violently and repeatedly shot at by the troops of Bombing Bernard is historically and archaeologically well documented by now, but the ‘bezondere’ (‘exceptional’) events described by De Hooghe in his day-by-day account are remarkable to say the least. One of these incidents involves a house being blown to smithereens. One complete sidewall of the house has been blown away, and yet by some miracle, a child lying in a crib in the room in question remains ‘fris en gezond’ (‘fresh and healthy’), as do its parents. Another incident involves a woman having a burning bullet shot between her legs as she sits on the pavement. Despite large sections of the pavement in front of and behind the woman being destroyed, she herself remained unharmed. And perhaps the most picturesque incident: the bomb falling on the house of Paymaster Emmius, blowing all the windows out of their frames, except one: ‘het Glas daar ’t Wapen van de Prins van Orangien in stondt’ (‘the window depicting the Weapon of the Prince of Orange’). According to De Hooghe, these events clearly showed that God was on the side of the young Republic and the House of Orange as they resisted the foreign attack.

To this day, we have no historical sources to either confirm or disprove the remarkable events described in this pamphlet, but it is reasonable to assume that they were the product of De Hooghe’s ideology and rhetoric. This shows to what extent narrative and observation can affect the way events are retold, and how with the help of the printing press, the story of the Siege of Groningen and De Hooghe’s views could spread throughout the Republic in the seventeenth century. In this way, the historical message underlying the study of such pamphlets remains relevant, as in a time when information spreads with unimaginable speed and sources are sometimes impossible to trace, it is all the more important to be aware of the connections between an event and its transmission, and how motives and rhetoric can colour communication.

Sources

- Daudeij, Frank, van Bunge, Wiep, and Krop, Henri. ‘Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) Op de Bres Voor de Burgerlijke Eenheid: Het Politiek-Religieuze Debat in de Republiek Rond 1700 Aan de Hand van de Spiegel van Staat (1706/07). Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2021.

- Nierop, Henk van. The Life of Romeyn de Hooghe 1645-1708: Prints, Pamphlets, and Politics in the Dutch Golden Age. Amsterdam University Press, 2018.

| Last modified: | 17 August 2022 5.47 p.m. |