Emo's Collateral

It’s not surprising that Abbot Emo regularly features in the Special Collections blog: his medieval chronicle covers the 12th and 13th centuries and is often the only source for the history of our region. In the centuries after this, barely anything can be found about the northern part of the country. Often, there are multiple copies of medieval texts, but in the case of this chronicle there is only one, plus a summary dating from the 17th century. Transcriptions and translations don’t appear until the 19th and 20th centuries.

Rereading a text always offers new insights. Unfortunately, this is also because Emo of Huizinge, despite the fact that he was very erudite—he studied at multiple universities, including the universities of Paris and Oxford—wrote a kind of Latin that later scholars such as Rudolph Agricola (1443–1485) abhorred. These humanists aspired to using clear Latin in the style of the great writers from Antiquity. If you read Emo’s chronicle, you see the difference. Our abbot’s wording is so cryptic, either consciously or subconsciously, that it is often unclear what he actually means.

And sometimes he is very concise when we, as 21st-century readers, would have preferred a more detailed account, instead of the elaborate self-reflections on sin—for example, on the question of whether selling ecclesiastical offices (called simony, something which was of course prohibited) was the cause of a punishment from God, in particular the heavy flooding and its thousands of victims among humans and cattle.

One account that is far too concise for our taste is of Emo’s journey on foot from Wittewierum to the Pope in Rome, from November 1211 until July 1212. What happened? The inhabitants of Wierum had donated their village church to Emo, to serve as the church of his monastery. The bishop of Münster, and local nobleman Ernestus in particular, realized this would mean that their earnings from the church and the lands would disappear, so they decided to take over the church. Emo decided that pleading his cause with the Pope was his last resort and he embarked on his 241-day journey. There are many questions surrounding his journey, but the biggest one concerns Emo’s collateral.

Emo actually managed to get a letter from the Pope (after fifty days in Rome!) that enabled him to secure his claim against the bishop and Ernestus. All’s well that ends well. He could start his journey home. But then the unsuspecting reader’s heart misses a beat, because what did Emo do, according to his own account, out of fear of losing this letter, his most prized possession? This is what the text says:

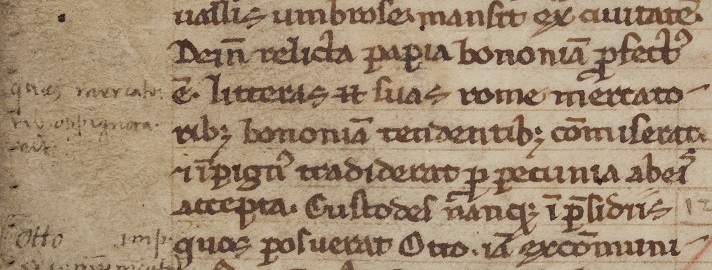

‘Litteras enim suas Rome mercatoribus Bononiam tendentibus commiserat et in pignus tradiderat pro pecunia ab eis accepta.’ (ill. 2) In Rome, he had given his letter as collateral to merchants who were travelling to Bologna, in exchange for the money he had received from them.

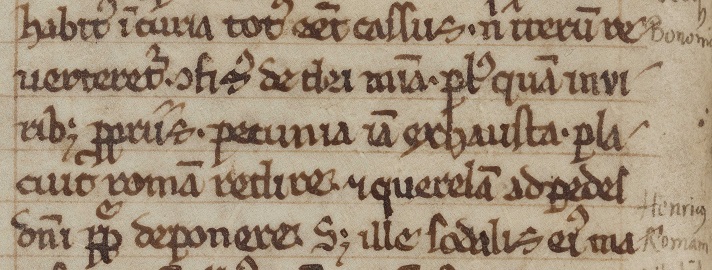

We find this extremely worrying. And rightly so: when Emo arrived in Bologna, he discovered that the merchants had been robbed and had lost his letter. And Emo had run out of money. ‘Pecunia iam exhausta’, he wrote (ill. 1). Emo was instantly brought down with onslaughts of fever. He suffered from extreme travel stress. He couldn’t see a way out of this situation. It is unclear how they managed to do this without money, but his travel companion Hendrik returned to Rome on his own. There, he received a new letter from the Pope and in the end, Emo and his companion could even afford a trip down the Rhine before they took up residence in their monastery. Ernestus and the bishop lost their case. What is left is a mystery that would make a great Dan Brown novel. But why did Emo decide to use the letter as collateral?

Did Emo give the Pope’s letter to the merchants because he believed that only clergymen such as himself were at risk of being robbed of their papal possessions at the guard posts of emperor Otto IV on their journeys from Rome? This is possible. But what did the merchants gain from this deal? Did they ask interest for the money they had loaned him? In the Middle Ages, the church had prohibited offering and asking for interest, under penalty of excommunication. It doesn’t sound very plausible that Emo, who was so worried about his salvation, would have violated this rule. And the papal letter was of vital importance to him, but not to the merchants. What could they have done with it, if Emo wouldn’t have paid back their money?

Maybe we are on the wrong track, looking at this with our 21st-century minds. The Middle Ages weren’t a time of reason. People lived between fear of God and trust in God. Considering Emo’s own account of his spiritual struggle with the question of whether he was a good man in the eyes of God, it is also possible that he gave the letter to the merchants to discover whether God deemed him worthy of the letter. After all, he only had to pay money for the letter, there was no soul searching involved. This could explain why he broke down when he heard the letter had been stolen, and recovered completely when Hendrik managed to get a new letter from Rome. They celebrated with a journey along the Rhine. Also, the merchants may have considered the letter to be a religious object or a talisman that could protect them on their journey. They turned out to be wrong.

| Last modified: | 27 July 2022 10.23 a.m. |