Studying the universe to understand the world

By understanding the cosmos, we can better fathom the fundamentals of our world. That is the idea behind the research theme Fundamentals of the Universe, in which three institutes of the University of Groningen form a unique collaboration. ‘Expensive particle accelerators have been built to learn how the smallest particles work in high-energy circumstances,’ says cosmologist Daan Meerburg, ‘but you can also see this in the cosmos.’ Recently, four PhD students defended their thesis on this theme; a fifth will follow soon.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text Charlotte Vlek | Images Leoni von Ristok

These particles are the same as in a particle accelerator, but the questions we ask ourselves about them are different

The big bang caused enormous amounts of energy to be released. High-energy situations can also occur in the case of supernovas or around black holes. The effects of such high-energy situations are flying around us right, left, and centre every day. ‘These particles are the same as in a particle accelerator,’ astrophysicist Manuela Vecchi explains. ‘But the questions we ask ourselves about them are different.’ For example, with a particle accelerator, the focus is often on the interaction between particles in a controlled situation, while Vecchi wants to know where these particles originated and why they have such a high velocity.

The building blocks and the manual

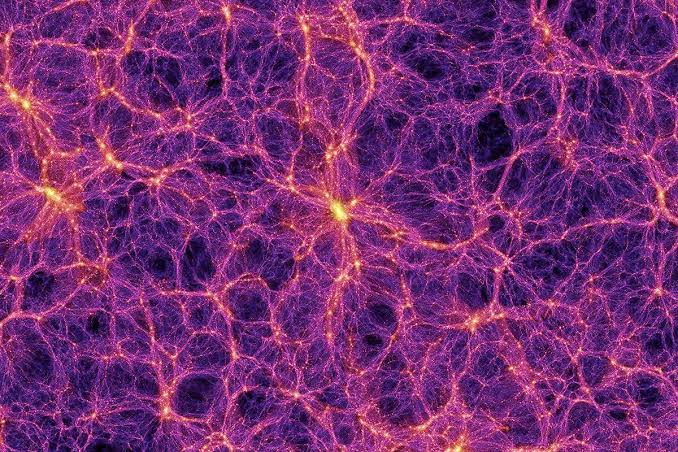

Vecchi and Meerburg mainly want to understand what the universe is built out of, and how it became what it is now. The building blocks and the manual, so to say. Vecchi is working on dark matter, among other things. She elaborates: ‘We know that there is an enormous amount of mass in the universe, much more than we can see.’ Therefore, something like dark matter must exist: something we cannot directly see, but that does have an effect on visible things.

Dark Matter

The effects of dark matter are visible, for instance, because objects in a galaxy move at a higher speed than is to be expected based on the visible mass. As a consequence, there must be some sort of invisible mass there. That is mainly evident in spiral galaxies, such as our own Milky Way.

‘Dark matter doesn’t emit or absorb light,’ Vecchi explains. And the same holds for other forms of radiation than visible light. ‘So, we currently have no way to detect dark matter directly.’

To show the existence of dark matter, Vecchi wants to observe gamma rays, a form of radiation with very high energy. Such radiation could be caused by interactions between dark matter, although other causes, such as a supernova, could be involved as well. Under supervision of Vecchi, PhD student Jann Aschersleben worked with an algorithm capable of identifying gamma rays in telescope images and reconstructing the energy of the initial gamma ray. The algorithm was developed by Michael Wilkinson from the Bernoulli Institute.

The next step is to aim the telescope at Omega Centauri, a globular cluster not too far from us. Vecchi recently submitted an observation proposal for this to the H.E.S.S. observatory in Namibia. ‘In Omega Centauri, an intermediate-mass black hole was recently discovered. Such a black hole is a suitable candidate for our research because there is often a lot of dark matter there, and because there are few other causes that could produce gamma rays.’

If you then observe gamma radiation, the cause is likely dark matter. ‘Even just detecting gamma rays would already be a good result. And if we can then show that other causes, such as supernovas, have not occurred nearby, that would be great!’ exclaims Vecchi.

From lumps to stars

Meerburg wants to learn how the universe has become what it is now. In the period after the big bang, the universe rapidly expanded in a short period of time, according to the theory of cosmic inflation. This expansion process is still ongoing, though at a much slower pace. In the early universe, there was no light and hardly any matter; there was only a sort of hydrogen mist. But small fluctuations during that rapid expansion somehow allowed lumps to form in that hydrogen mist. These lumps grew, because they attracted more particles due to gravity, until ultimately stars and galaxies formed.

‘But why are there more stars and galaxies in some places than in others?’ Meerburg wonders. Or, in other words, what initial conditions caused by these fluctuations have led to the spread of stars and galaxies as we now see them? To study this, cosmologists like Meerburg look at radiation that originated in this very early universe. But the radiation as it reaches us now has been deformed under the influence of gravity.

Many people assume that everything was still “tidy” in the early universe

PhD student Thomas Flöss, under supervision of Daan Meerburg, Leon Koopmans, and Diederik Roest, worked on simulations that map out just how this radiation was perturbed, and what we can derive from it. Meerburg: ‘We understand quite well how gravity works, and we can simulate the effect of it quite precisely. By showing images to the computer of how the universe looks now and how it looked just after the big bang, we trained a computer model to undo the effects of gravity on the radiation.’

Flöss’ surprising conclusion was that even in this very early universe the radiation has been perturbed, despite the fact that gravity has had little opportunity to perturb it there. Meerburg: ‘Many people assume that everything was still “tidy” back then, but we have shown that you then form an inaccurate image of this early universe.’

| Last modified: | 03 February 2025 2.38 p.m. |

More news

-

25 April 2025

Leading microbiologist Arnold Driessen honoured

On 25 April 2025, Arnold Driessen (Horst, the Netherlands, 1958) received a Royal Decoration. Driessen is Professor of Molecular Microbiology and chair of the Molecular Microbiology research department of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the...

-

24 April 2025

Highlighted papers April 2025

The antimalarial drug mefloquine could help treat genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, as well as some cancers.

-

22 April 2025

Microplastics and their effects on the human body

Professor of Respiratory Immunology Barbro Melgert has discovered how microplastics affect the lungs and can explain how to reduce our exposure.