Phase contrast microscope

In his Nobel Prize speech, Zernike mentioned how he could have initially called his invention a ‘phase-strip method for observing phase objects in good contrast’, but that he settled on the shorter ‘phase-contrast method’. Using a flat, glass strip, the phase-strip, he was able to increase the contrast of an object that would otherwise be difficult to see.

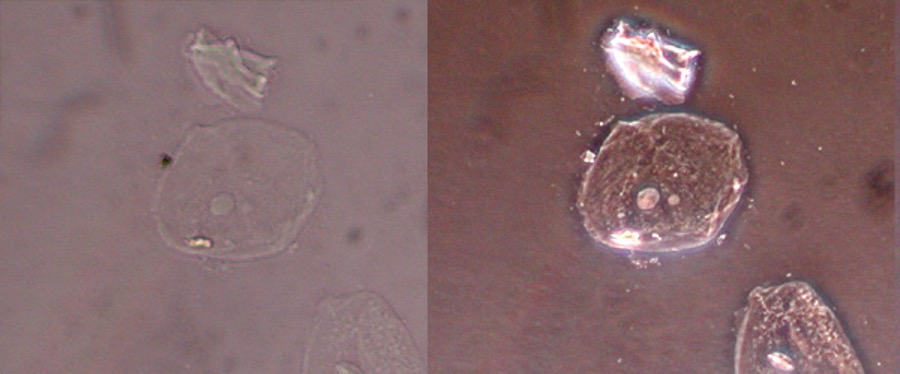

An important example of such an object that would otherwise have been hardly visible is the living cell. You previously had to colour cells to make them visible, but by colouring them, you would kill them. With Zernike’s method, it became possible to study living cells.

How does it work?

A traditional microscope enlarges the image of an object with a lens. But a transparent, colourless thing, such as a living cell, is hardly visible this way. Adding more light or further enlarging the image doesn’t help.

When light passes through such a transparent object, something does happen to the light waves though: they slow down a tiny bit because they are passing through another material. Something similar happens when you look through clear water; a straight pole that sticks out of the water appears to bend at the surface.

The slowing down of the light waves creates a phase difference, which means that the highs and lows of the waves are no longer entirely in sync. This phase difference varies, depending on the object that the waves pass through, and Zernike was able to adjust the phase difference in order to create larger contrasts in the image.

Adjusting the phase difference to create more contrast is done with a glass strip that has thin, etched lines on the surface and is built into the microscope. These lines make the light waves sync up again, which means that they amplify each other and become more visible.

Watch the video below about phase-contrast microscopy. The video was made by the UG fifty years after Zernike received his Nobel Prize.

| Last modified: | 24 October 2023 4.23 p.m. |