Digital Methods for Corpus Expansion in Early Modern Philosophy Research

| Date: | 18 September 2019 |

| Author: | Raluca Tanasescu; Andrea Sangiacomo; Silvia Donker; Hugo Hogenbirk |

In September 2019 we presented a poster at the DH Benelux annual conference, organized at Université de Liège (Belgium), in which we reported on the initial corpus expansion stage and its attendant digitally-inflected methodologies of the ERC-funded research project “ The Normalization of Natural Philosophy: How Teaching Practices Shaped the Evolution of Early Modern Science .” (PI: Andrea Sangiacomo) The main contention of our project is that these teaching practices were socially embedded and had a decisive ‘normalising’ impact on the progressive dissemination, adaptation, and selection of rival conceptions of natural philosophy (Sangiacomo 2018).

Two major axes of research are followed to this end. The first one involves social network analysis, which reconstructs the networks of authors and sources that were involved in the debate on early modern natural philosophy and their evolution over time. The second one uses semantic network analysis, which rebuilds the networks of concepts of natural philosophy, their linguistic context and vocabulary, and explains why certain concepts and approaches become accepted as standards, and which elements determined this output. The work we presented at DH Benelux 2019 outlines the methodology used for the initial building of the corpus on which the two kinds of network analyses will be carried out.

We aimed to answer the following questions:

- Are the sources listed in the Dictionaries of early modern philosophers—Dutch (van Bungeetal 2003), British (Yoltonetal 1999 and Pyle 2000), and French (Foisneau 2008)—complete? If not, how much do these established sources miss?

- How could we best create lists of authors and works for geographic regions and periods that are not covered by the Dictionaries (e.g. eighteenth-century French philosophers)?

- How representative is the corpus derived from the dictionaries with respect to the overall corpus that can be collected via the World Cat?

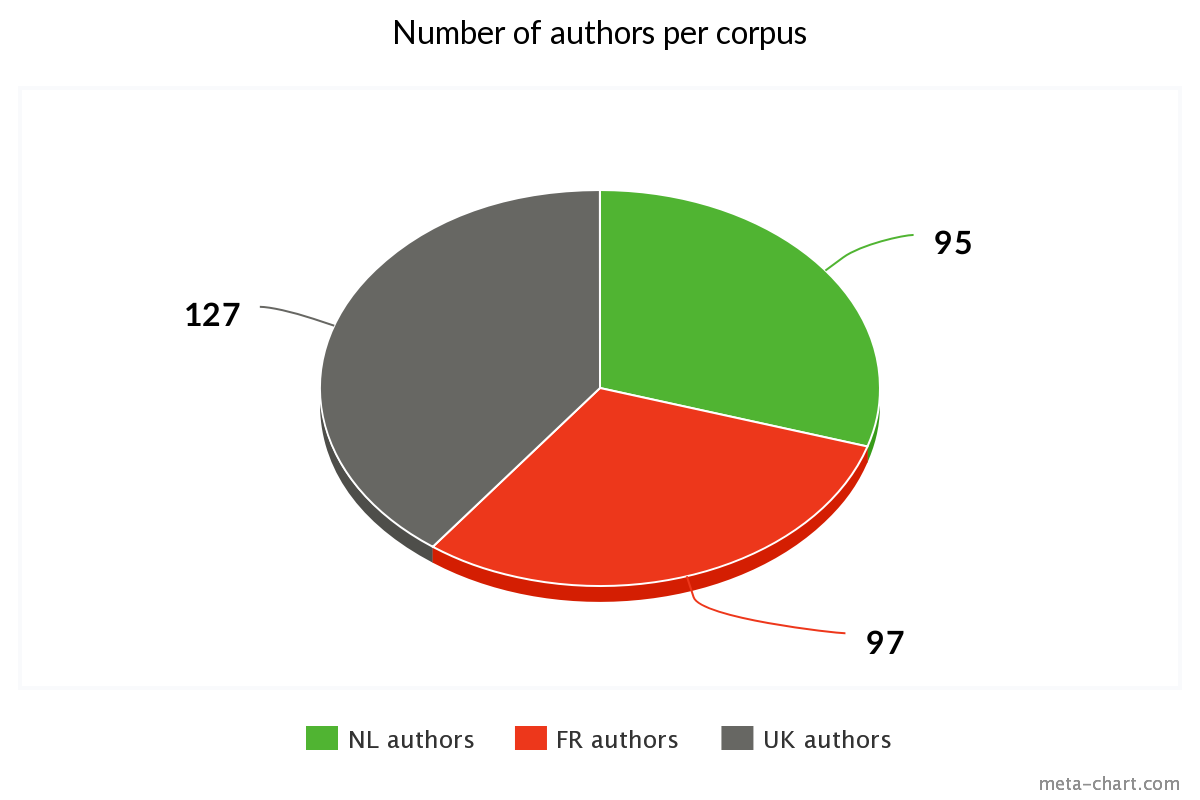

The team have departed from the existing dictionaries of Dutch (van Bunge et al. 2003), British (Yolton et al. 1999 and Pyle 2000), and French (Foisneau 2008) early modern philosophers (1600-1800)

and created a dataset of associated relevant works divided into three broad categories meant to differentiate between their contribution to the dissemination and normalization of teaching practices:

- ‘primary’—clearly systematic in nature, most comprehensive, most likely to be used as teaching materials and offer less doubts about the fact that they concern natural philosophy as a whole;

- ‘secondary’—similar to primary works except that they are not necessarily systematic (i.e. student disputations), often offering a glance at more specific core issues that are debated in the discipline across time and space; and

- ‘tertiary’—not necessarily connected with natural philosophy but show a relevant use of key notions, debates or trends in natural philosophy for related topics and discussions.

METHODOLOGY

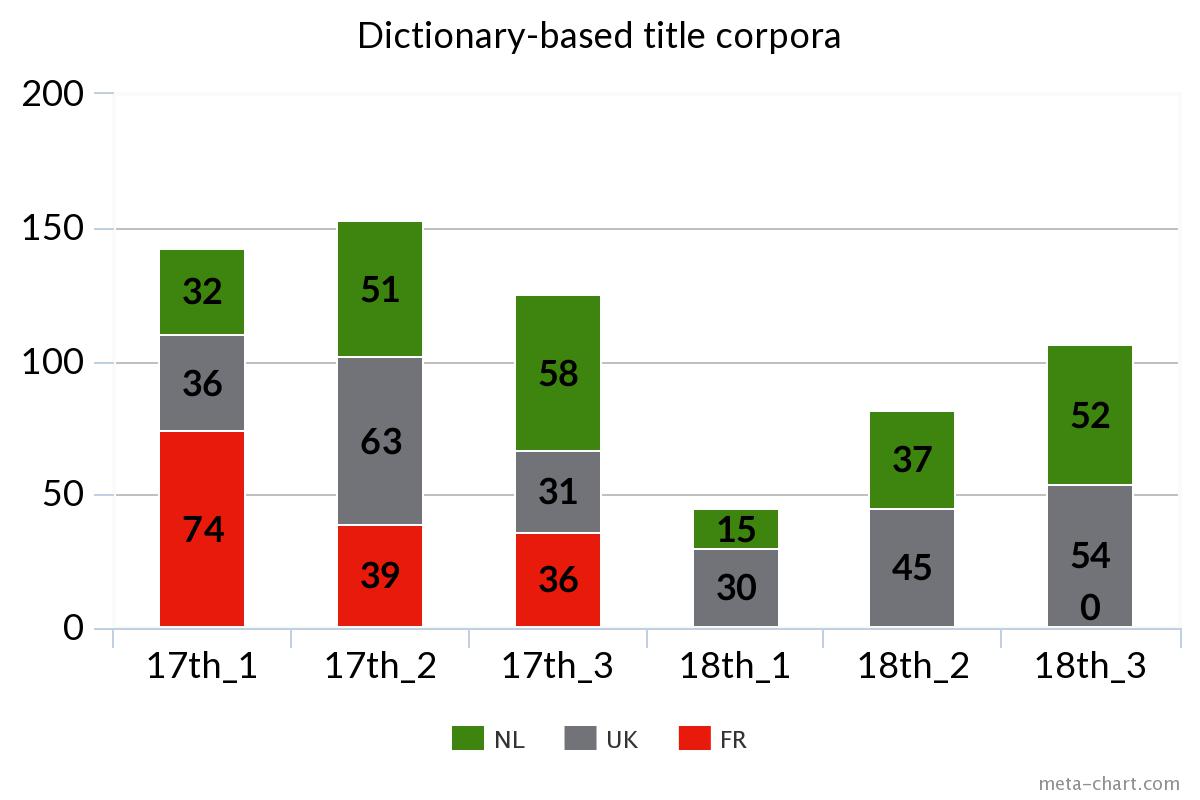

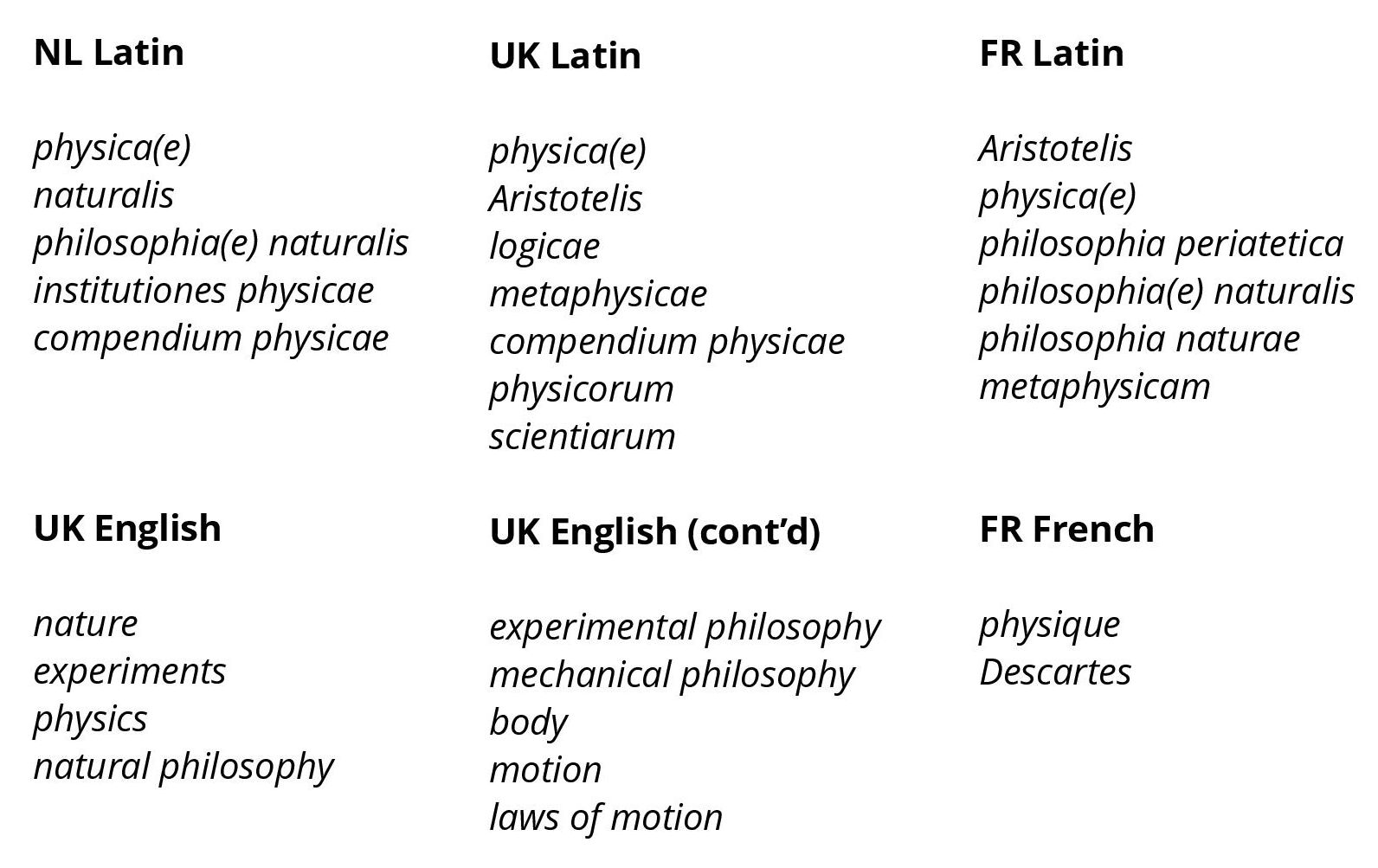

Keyword identification: In order to expand these sets of relevant writers and works and to explore the ‘unread’ debate on early modern natural philosophy, we have derived lists of frequent words and frequent collocations from the titles as follows: for each language (Latin, French, and English), for each corpus (Dutch, British, and French), and, within each corpus, for various time clusters (periods during which works of natural philosophy have been published regularly, without significant gaps between two consecutive titles). Since we have not performed “whole-text” searches (Tangherlini and Leonard 2013) and we have rather faced small-sized departing corpora of titles in the existing bio-bibliographical dictionaries (several hundred words each), simple word frequency counts were deemed sufficient (Graham et al. 2012). We retained both keywords that were semantically related to ‘physics’ or ‘natural philosophy’ or two-word collocations consisting of a more general term, such as the Latin philosophia, and a more specific one (e.g. naturalis). We set the bar to three occurrences for single keywords and to two for collocations and lowered the threshold to two occurrences in the case of small corpora, such as the first French time cluster of only seven titles.

Web-crawling and scraping: The lists of keywords and collocations obtained via the open-source concordancer AntConc were then used for focused web-crawling and scraping the WorldCat catalog by means of a Python script, which collected a total of over 74,000 titles published in Latin, English, and French between 1600 and 1800. As expected, the corpus contained a very large number of duplicates, as well as numerous instances of titles not pertaining to the field of philosophy due to the semantic loading of several keywords.

Messy data cleaning: The large amount of scraped information was first cleaned, simplified and tokenized via the pandas, numpy, os, string, and NLTK Python libraries.

Two-step data deduplication: Subsequently, the .csv files created for each keyword and collocation were further analyzed and processed to remove all duplicates, as well as to remove the data already present in the three existing dictionaries. The data deduplication was done by substring similarity matching via the FuzzyWuzzy library, which assigned similarity scores to authors and titles and removed those with values generally over 60%.

Manual annotation: The remaining data were then analyzed using close reading in order to eliminate any works not pertaining or not related to the field of philosophy, to break down the final results into the three working categories and, finally, to divide the resulting lists of authors by nationality and retain those of interest.

RESULTS

CONCLUSIONS

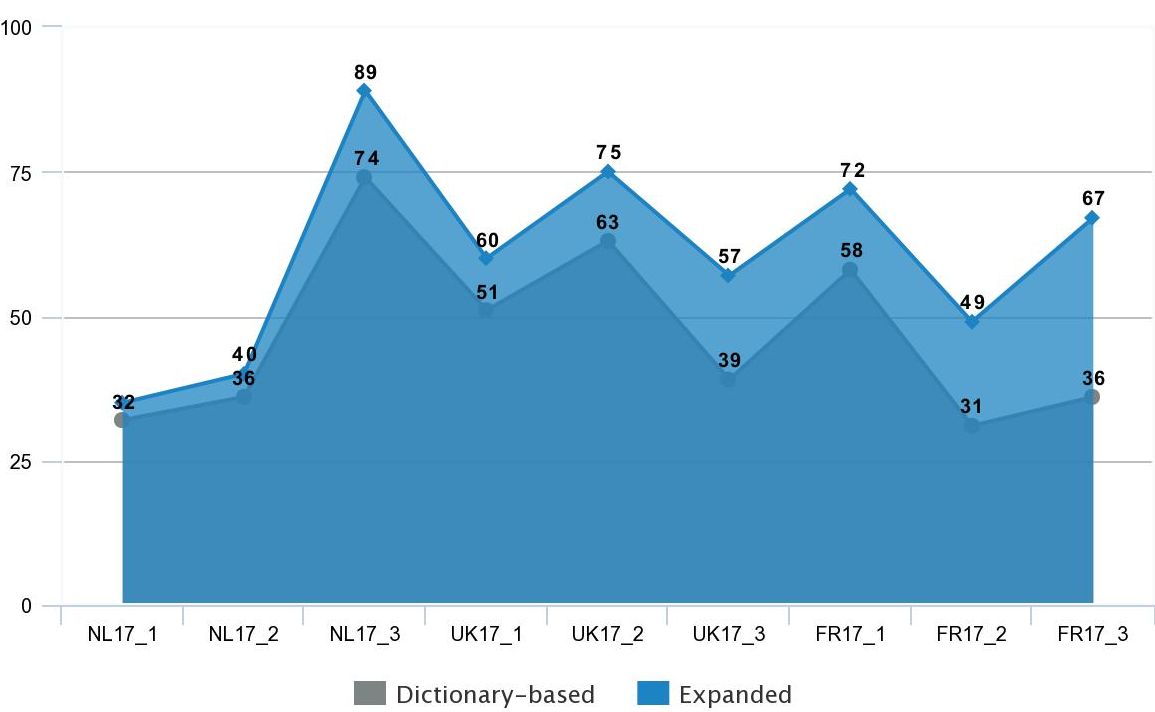

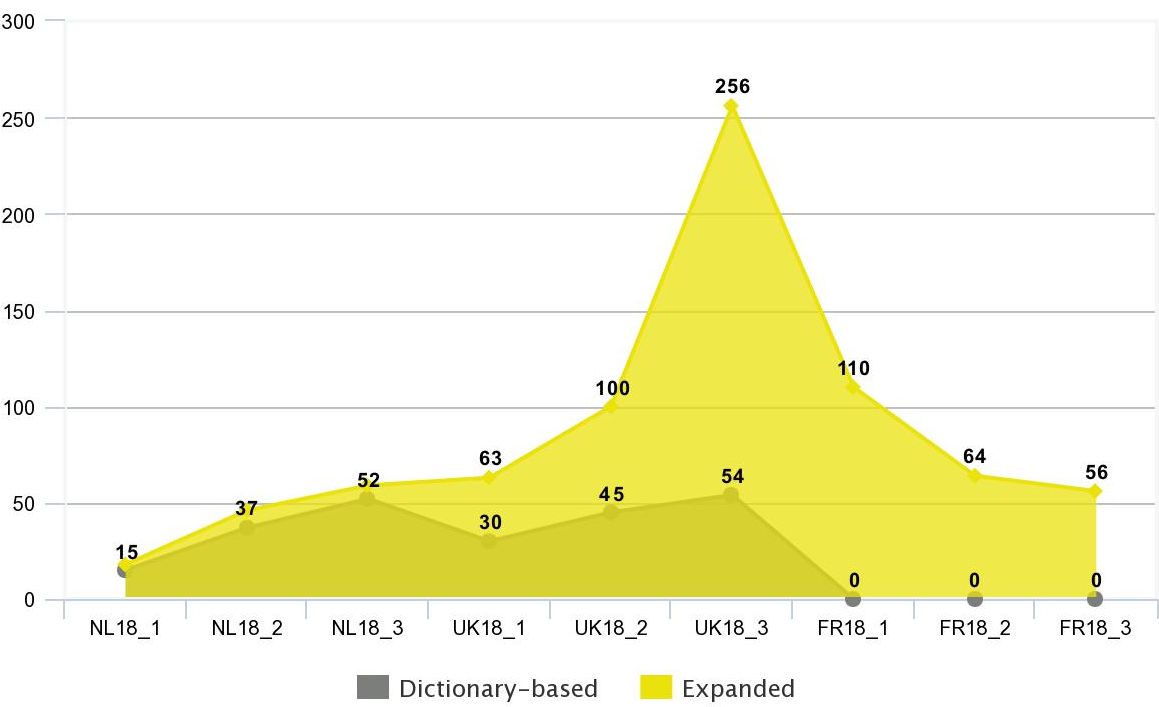

1. Bio-bibliographical dictionaries are sufficiently complete (especially the dictionary of Dutch philosophers) and the expansion we generated remains within 29% of the original amount of 17thc. sources included. Secondary titles are also more likely to be glossed over or omitted by Bio-bibliographical Dictionaries, given that they are mostly student disputations, theses, and other relatively ephemeral works whose authorship is often unclear. The exception is the amount of tertiary works recovered for the 18th-century British Dictionary. Most of the 207 titles distilled from WorldCat concern the debate on electricity and other experimental matters that boomed during the period but were understandably omitted by the Dictionary. They increase the average expansion of 18thc. sources from 65% to 136%.

2. In trying to make an inventory of authors and works for time-space quadrants not covered by existing Dictionaries (18th-c France, in our case), we assumed that it is possible to at least identify sources more or less similar to those produced in other quadrants. Our initial expectation was that our method would miss tertiary works because their titles are less standard and are best identified by studying the authors and their philosophical orientation in a more traditional top-down manner. However, our results show that the WorldCat scraping identified a number of tertiary works for the missing quadrant (Fr, 18th-c) similar in size to that identified for the other quadrants based on existing Dictionaries. The amount of primary and secondary works for 18th-c Fr quadrant make the newly generated corpus comparable in size with that based on Dictionaries for other quadrants. Although some caution should always be kept concerning the ‘completeness’ of the lists generated by WorldCat, it seems safe to maintain that they give a good sense of the sources in a given time-space quadrant.

3. While Dictionaries are active but limited sources of information (they directly point towards authors and works that have been considered relevant by informed scholars who compiled the Dictionaries themselves), WorldCat is an unlimited but passive source of information (it contains much more than what is covered by the Dictionaries, but this information is so vast that it cannot offer itself and therefore needs to be retrieved using some methods, like keywords search). We tried to combine the strengths and limitations of these two sources of information by building a circular method that can progressively lead to expand our corpus and also generate a benchmark for assessing its representativeness.

One limitation we see is the missing works whose titles and metadata do not contain our keywords. Our method reveals that we cannot entirely overcome this bias by simply relying on online resources and library catalogues. However, searches on WorldCat do include the metadata, which limits the said bias. Finally and more importantly, acknowledging such shortcoming also calls for a renewed effort to explore in depth areas of the early modern intellectual landscape that are still neglected by recent scholarship.

Works cited

Foisneau, Luc. 2008. Dictionary of Seventeenth-Century French Philosophers. London; Oxford; New York; New Delhi; Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Graham, Shawn; Weingart, Scott; Milligan, Ian. 2012. “Getting Started with Topic Modeling and MALLET.” The Programming Historian 1

Pyle, Andrew. 2000. Dictionary of Seventeenth-Century British Philosophers. London; Oxford; New York; New Delhi; Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Sangiacomo, Andrea. 2018. “Modelling the history of early modern natural philosophy: the fate of the art-nature distinction in the Dutch universities,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy, DOI: 10.1080/09608788.2018.1506313.

Tangherlini, Timothy R.; Leonard, Peter, 2013. “Trawling in the Sea of the Great Unread: Sub-corpus topic modeling and Humanities research.” Poetics, 41(6), pp.725-749.

van Bunge, Wiep; Krop, Henri; Leeuwenburgh, Bart; Schuurman, Paul; van Ruler, Han; Wielema, Michiel. 2003. Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers. London; Oxford; New York; New Delhi; Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Yolton, John; Price, Valdimir; Stephens, John. 1999. Dictionary of Eighteen-Century British Philosophers. London; Oxford; New York; New Delhi; Sydney: Bloomsbury.