A molecule builder

The eyes of the brand new Nobel Prize winner are full of excitement and emotion, due to a love of life and his work. Feelings of disbelief, happiness and thankfulness visibly struggle for prominence. This is the real Ben Feringa: a brilliant and passionate scientist, as well as a warm and sensitive person.

Talent and inspiration

When asked what the secret is to successfully keeping a research group at the top of its field in the world, he falls silent. He then says: ‘It is my privilege to work with unbelievably talented young people. It is a team of people from 18 different countries all looking for scientific challenges, who think: What is the real question here?’

"It is my privilege to work with unbelievably talented young people.’"

He has also been teaching 1st and 2nd-year students for over 30 years. When he was a third-year student, he fell in love with the field thanks to the teaching of his professor, Hans Wijnberg. ‘He inspired me to do original things, to look beyond the frontiers. It was in his lab that I made a new molecule for the first time. I got such an enormous kick from that – your own molecule… building your own world. I instantly gave up all my plans to switch to mathematics.’

Happy in Groningen

In 1988, Feringa succeeded his mentor and has continued to try and maintain the same atmosphere. ‘Wijnberg was full of ideas, loved tackling new things and was able to make everybody enthusiastic. He treated his students as fully fledged partners in his research. There was an ambitious atmosphere throughout the entire organic chemistry lab; we wanted to be the best. It is important to create an atmosphere in which people work in the true vanguard of science, who want to go beyond the frontiers.’ Personally, Feringa is less interested in crossing geographical boundaries: ‘I am so unbelievably happy that I am in Groningen, and that I have stayed in Groningen.’

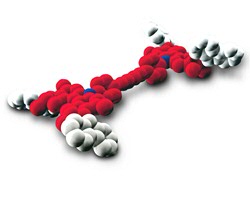

Four-wheel-drive molecular car

‘I am a molecule builder,’ says Feringa: ‘I try to make clever molecules. It’s not really that hard to make a moving molecule, the point is that you have to be able to steer it, that you have control over what happens. The same applies to catalysts, molecules that help a substance turn into another substance. What you want is for that single product to be created and not a mishmash of molecules.’ This is why Feringa practices nanotechnology: his building blocks are molecules at the scale of 1 millionth of a millimetre, a nanometre. That’s unbelievably small, and yet in 1999 he successfully invented a molecular motor driven by light, a spectacular discovery that garnered attention throughout the world. Following this, in 2011, he made the cover of the scientific journal Nature with his four-wheel- drive molecular car.

Playing fields for science

The Nobel Prizewinner is an advocate of fundamental research: ‘There are questions to which the answer and the route to the answer are more or less known. The real challenges lie right at the other end of the spectrum, where the route is unknown, and where we often don’t even know the right question and certainly not the answer. Universities are places where rebellious ideas can emerge, there is great freedom to think in whatever direction you want. They are the playing fields for science. And it should stay that way.’

| Last modified: | 20 April 2021 10.00 a.m. |