How human prejudices sneak their way into computer programmes

Language technology has developed so incredibly fast in recent years that we can no longer imagine life without it. Applications such as autocorrect, Google Translate, and Siri are woven into our daily lives. But according to Prof. Malvina Nissim, Professor of Computational Linguistics and Society, such developments are not without their risks. It concerns her that users seldom stop to consider the active role that they themselves play in the development of language technology. Nissim will give her inaugural lecture on 2 December.

By Marjolein te Winkel / Photos Henk Veenstra

We tell Siri to call ‘home’ to save us having to enter a number. We use Google Translate to translate texts and we get Word to check our spelling. And in WhatsApp, we only have to type in a couple of letters and we’re given a number of possible words to choose from. These and the many other applications and services that so many of us have embraced are based on computational linguistics: the field where linguistics and artificial intelligence meet.

Weird translations

It’s no surprise to Malvina Nissim that we’re all so fond of technology. ‘I am too. As an Italian working at a Dutch university, I’m forever receiving documents written in Dutch. It takes me ages to plough through them all, so sometimes I get Google Translate to help me. A few years ago, the translations it generated were often pretty weird, but these days they’re really good. Good, but not perfect. Computers make mistakes.’

For example, things can go wrong if a colloquialism is translated literally. Each word may have been translated correctly, but the meaning is lost. Mistakes can also arise, explains, Nissim, from prejudices that a translation machine has been taught, even unwillingly. `Take my native language, Italian. Italian is gender-marking, meaning that its words can have a masculine and a feminine version. You always have to make a choice. I’m a female professor: una professoressa. A male professor is un professore. But if I ask Google Translate to translate `I am a professor’, it will go for the masculine word for professor, unless I specifically state that I’m a female professor.’

Prejudices and stereotypes

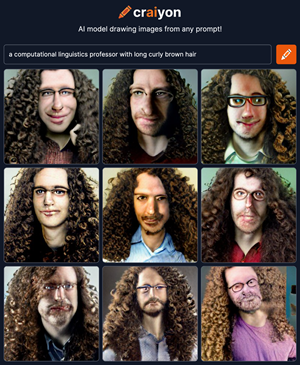

Such prejudices are not unique to translation machines. If you google images of professors, most of the images you get will be of white men with glasses, standing in front of old-fashioned chalkboards. ’`Or there’s a recent system, Crayon AI’, Nissim says, ’`that draws images based on text prompts. If I want to get it to draw me and I type in: ‘a professor of computational linguistics with long, brown, curly hair’, it gives me nine options. And all nine of them are white men with long, brown, curly hair and glasses.’

Nissim is quick to point out that simply blaming the technology for these prejudices would be myopic. `We develop these programmes by showing the computer lots and lots of examples. And those examples are derived from the texts, images and so on that you and I leave behind on websites and in documents. Programmes learn from the language we use. All they are doing is adopting the prejudices and stereotypes that we have expressed, usually without being able to add any nuance to them.’ It’s a fact that there are more men than women in senior positions, such as that of professor, and we end up talking and writing more about male than female professors. `But female professors do exist of course, and this is knowledge that the computer must get’, Nissim says.

Reducing prejudices in computer programmes is certainly possible, but it’s not easy. `It entails intervening at the development stage and also deciding what is a prejudice and what is not,’ Nissim explains. `Gender is quite a clear example, even when just considered in a simplified binary form, but there are other prejudices that are much more subtle and therefore much more difficult to combat.’ Another issue is that the data is not representative of society as a whole. `Not everyone is active online and not everyone is represented in the data that is used to train computer models. For example, some languages are used far less frequently than others and some ethnic groups are under-represented. We need to be aware of that too when we’re using data to build new applications.’

Awareness

In order to pass this awareness on to future generations, Nissim and her colleagues have developed a series of lectures for third-year Information Science students at the Faculty of Arts about the ethical aspects of computational linguistics. `This is the new generation that will be making applications in the future. As well as acquiring technical knowledge, it is important for them to think about the potential impact of the technology they are developing.’

Nissim wants to get this message across not only to programmers but also to users. `It’s important for all of us to realize that these computer programmes are not objective and that not everything we find online is true’, she says. `There are programmes available now that can make extremely realistic videos based on text. They look amazingly real, but nothing you see in the video actually happened. The tools that are being developed to detect false information are getting better and better, that’s true, but the technology being used to concoct that information is advancing just as fast.’

That said, the last thing Nissim wants is for people to be afraid of technology. `It’s fantastic to see how much can be done, and of course we want to make full use of all that potential. It’s just that we need to be aware that computer programmes are not perfect. We must remain critical when deciding how to apply what is technologically possible, and that requires people and machines to work together. As long as we do that, we can keep welcoming new developments.’

About Malvina Nissim

Prof. Malvina Nissim (1975) studied Linguistics at the University of Pisa and gained her doctorate in 2002 for a thesis entitled ‘Bridging Definites and Possessives: Distribution of Determiners in Anaphoric Noun Phrases’. She worked at research institutions in Edinburgh, Rome, and Bologna before joining the Faculty of Arts at the University of Groningen in 2014, where she was appointed Professor of Computational Linguistics and Society in 2020. She was elected UG Lecturer of the Year in 2017.

Nissim heads a research team that is currently working on the further development of applications that support language-based interaction. The team uses computer models to research how language and language-based communication work. A recent publication written by Nissim together with UG doctoral candidate Gosse Minnema, UG researcher Dr. Tommaso Caselli, and two colleagues from the University of Pavia (Chiara Zanchi and Sara Gemelli) on computational linguistics research with high social impact has just been selected as best paper at an international conference on language technology.

More information

- Malvina Nissim

- Nissim will hold her inaugural lecture on Friday 2 December.

| Last modified: | 14 September 2023 1.56 p.m. |

More news

-

12 March 2025

Breaking news: local journalism is alive

Local journalism is alive, still plays an important role in our lives and definitely has a future. In fact, local journalism can play a more crucial role than ever in creating our sense of community. But for that to happen, journalists will have to...

-

11 March 2025

Student challenge: Starting Stories

The Challenge Starting Stories dares you to think about the beginning of recent novels for ten days.

-

11 March 2025

New: Sketch Engine, tool for language research

Sketch Engine is a tool for language research, which can also be used for text analysis or text mining.